D.C. Kent survived his self-inflicted wounds. The bullet wound in his head was superficial and the gash in his throat healed. With no chance of succumbing to his injuries, D.C. decided to lay the groundwork for his defense.

Too bad D.C. wasn’t an actor or he would have known better than to break character in the middle of a performance. He pretended not to hear when someone spoke to him. He rolled his eyes and did everything but drool. Whenever someone took him by surprise, he dropped the pretense. The deputies in the jail ward at the receiving hospital saw through his act, and so did the trusties.

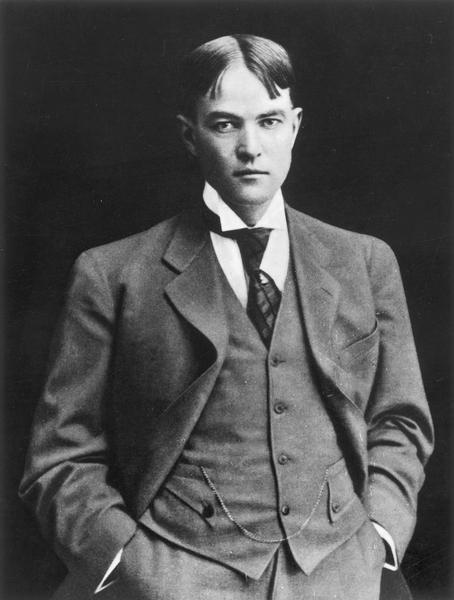

A clue to D.C.’s state of mind was obvious in his choice of a lawyer. An insane man would not care if he had a lawyer or not. D.C. cared enough to engage the services of one of the best criminal defense attorneys in the country, Earl Rogers.

Earl Rogers, admitted to the California bar in 1897, was an attorney of uncommon skill. He appeared for the defense in seventy-seven murder trials and lost only three. During one of his most famous cases, “The Case of the Grinning Skull,” Rogers introduced the victim’s skull into evidence to prove that what looked like a fracture caused by a violent blow from a blunt instrument, delivered by his client, was, in reality, the result of the autopsy surgeon’s carelessness with a scalpel. The jury acquitted Rogers’ client.

If you think that “The Case of the Grinning Skull” sounds like the title of a Perry Mason novel, you’re not far off. A decade after Rogers’ death in 1922, author Erle Stanley Gardner resurrected Rogers in the character of Perry Mason.

Rogers visited D.C. in jail. D.C. was despondent, whiny, and in a state bordering on nervous collapse. He dropped his insanity act and asked Rogers to tell him if he had any chance of an acquittal. Rogers pulled no punches. He told D.C. he would have to get a grip on himself or the chances of him walking out of the courtroom a free man were zero to nil.

D.C. then asked Rogers about the worst-case scenario. What would happen if a jury convicted him? Again, Rogers leveled with his client. He told D.C. he might get from one to ten years in the penitentiary. D.C. collapsed. D.C.’s next question was about Rogers’ fee. Rogers had had enough of D.C.’s hand wringing and complaining. He said,

“Even if it costs you everything you have; it would be cheaper than going to the penitentiary.”

Rogers urged D.C. to be a man, not a coward. His plea fell on deaf ears.

While D.C. and Rogers talked, a patient was admitted to the hospital. To treat the patient, someone opened the large medicine cabinet near D.C.’s bed.

D.C. made a move to get up from his cot, but Special Officer Quinn entered the room and D.C. sat back down. As Quinn turned to leave, D.C. got up to follow him. He said he had to use the restroom.

Before anyone could stop him, D.C. sprang to the open medicine case, threw back the doors and grabbed a bottle of carbolic acid. He poured most of the bottle’s contents down his throat. Some of the caustic liquid spilled down his shirt and burned him.

Deputies grabbed D.C. and carried him to the operating room. He frothed at the mouth and writhed in agony, but said nothing.

A doctor was at D.C.’s side within 5 minutes. The doctor administered the antidote, but it was too late. Ten minutes later, D.C. died.

Deputies searched the dead man’s cell and found a letter to Hattie.

The letter read:

“Dear, Dear Hattie: I suppose that sounds queer to you. This is the longest time in seven years that I have not heard from you. Now I ask you if possible, to forgive me. Next, if possible, to assist me in my greatest hour of trouble.”

Unbelievable. D.C. had the unmitigated gall to beg Hattie, the woman he attempted to murder, to assist in his defense.

True to his character, D.C. continued:

“I am suffering the tortures of hell. I wish you could know one-half of my life in the last thirty days. Now, Hattie, I shall be plain with you and am going to ask you to return kindness for unkindness.”

The letter rambled along in a self-serving fashion to its conclusion, which was a pathetic plea:

“Oh, I beg you, save me, for it is all with you. Think of me in jail, all covered with filth and lice; only beans and bread and treated like a dog. Save filthy me, I beg of you. Please tell Mr. Rogers your feelings in the matter.”

D.C. lied about the conditions in his cell and his treatment. Everyone who came in contact with him recalled him as, “troublesome, peevish, and fretting constantly because he could not do as he pleased.”

On the date scheduled for D.C.’s arraignment, Justice Morgan dismissed the case because of the “death of the defendant by suicide.”

A former associate of D.C.’s paid to ship the body to Burlingame, Kansas.

In his will, D.C. deeded Hattie his interest in the furniture of the Columbia lodging house. Small recompense for the agony she endured.

EPILOGUE

Hattie survived her wounds and married. George thrived. He served in World War I. Following the war, he became one of the first motion picture art directors. In 1924, he married Thelma Schmidt, and Hattie was there.

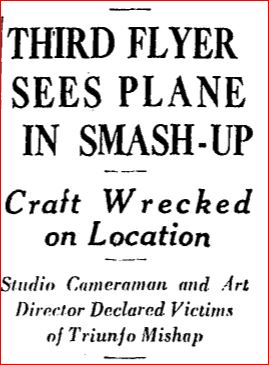

Late in the afternoon on June 29, 1935, George and veteran cameraman Charles Stumar left the Union Air Terminal in Burbank. They headed to a location near Triunfo where they planned to scout locations for an upcoming Universal Pictures film.

Stumar brought the plane in for a landing on an improvised field owned by the studio. It was twilight; the field was rough and uneven. Martin Murphy, a production manager for Universal, witnessed the crash. He telephoned the studio to report the accident and to let them know that he believed both occupants of the aircraft to be dead.

Upon hearing the news, Captain Morgan of the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s aero detail hopped into his plane to survey the scene. When he arrived he confirmed everyone’s worst fears.

George’s death devastated Hattie.

The 1940 census shows Hattie living in the Manor Hall Rest Home on 1245 South Manhattan Place in Los Angeles. She passed away on October 22, 1951.

Hattie and George are buried in adjoining plots at Forest Lawn Cemetery in Glendale.