Driving east on Ventura Boulevard in North Hollywood (now Studio City), architect Julian L. Zeller saw a well-dressed man staggering out of the weeds on the south side of the street. Zeller stopped to render aid. The man said, “I was shot by bandits in the hills. The bandit stole my car and my sweetheart.” Then he said, “If I die, tell my wife I loved her.” The man bled profusely and grew weaker as Zeller rushed him to the Hollywood Receiving Hospital. Zeller assisted his injured passenger into the hospital’s emergency room. Doctors tried, but they could not save the man.

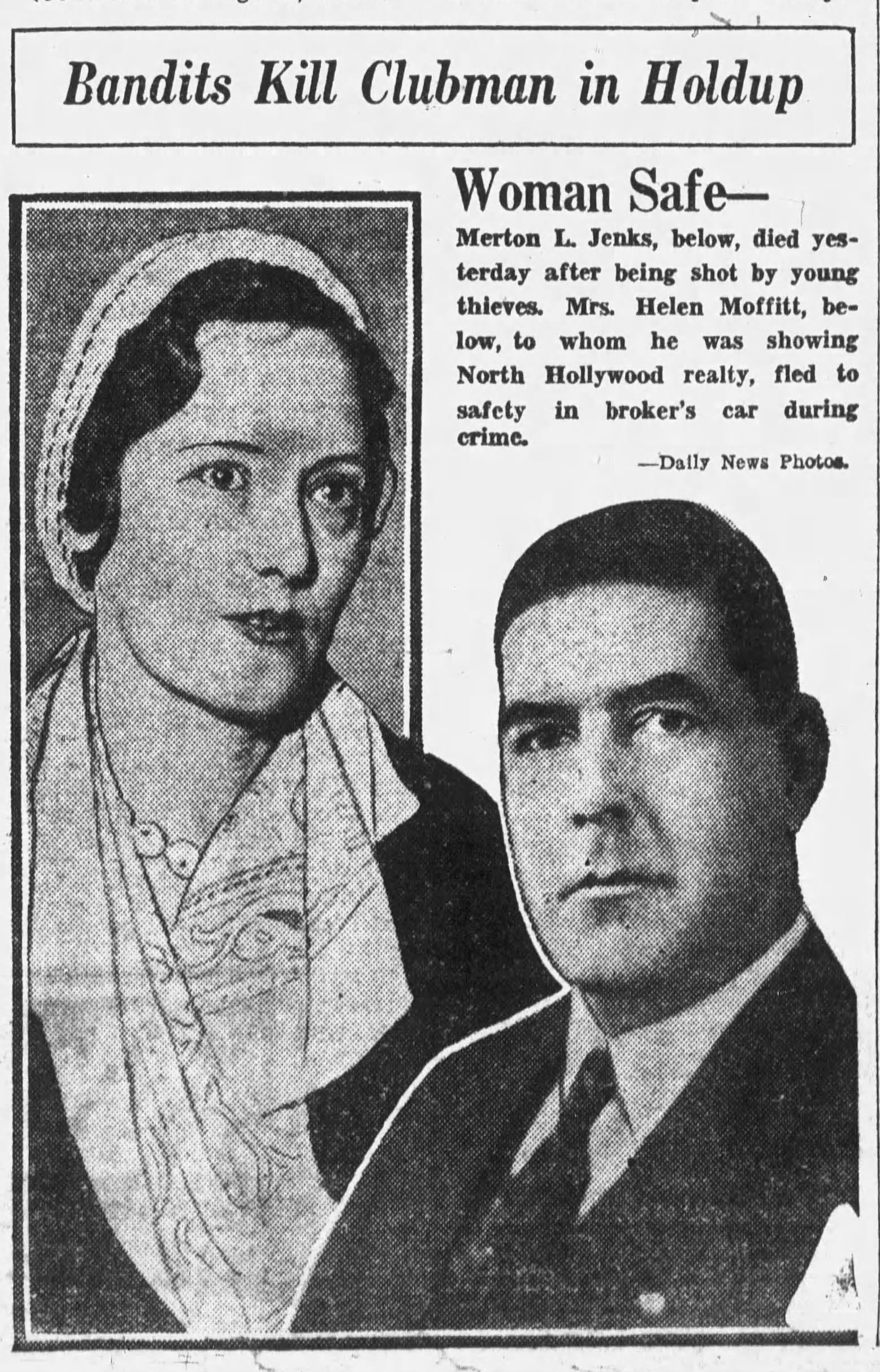

From the contents of his pockets, police tentatively identified the deceased as fifty-one-year-old Merton L. Jenks. Merton, a wealthy real estate broker and oil speculator, lived in Beverly Hills with his wife Ruby. A prominent member of the Los Angeles Athletic Club, Merton had friends in high places, like the Police Commissioner.

As detectives contemplated their first steps in investigating Merton’s death, motorcycle officer J. E. Clementine sped to answer a call at 11414 Berry Street in the hills above Ventura Boulevard. The resident, Mrs. J. B. Mield, phoned because a woman arrived at her doorstep pleading for help.

Clementine guided his bike to the curb of the Berry Street home and found a hysterical woman in the yard. The woman choked out her name, Helen Moffitt. She calmed down enough to tell Clementine that she and a companion, Merton Jenks, were the victims of a hold-up at the top of the hill.

Helen said she did not know what happened to Merton. As soon as he grappled with the armed robber, she took off in the car to get help.

Chief Detective Joe Taylor and Inspector David Davidson took Helen downtown to LAPD’s Central Station for questioning. They contacted her husband, Norval, a Glendale car salesman, and he joined them.

Detectives asked Helen how well she knew Merton, and why they parked on a lonely road in the hills. She said, “I met Mr. Jenks at my sister’s home about a year ago. He knew that myself and my husband were anxious to dispose of our house in Venice and he was interested in showing me some new places. Tuesday, he called for me at home and we went to the North Hollywood district. We drove up to the head of Berry Drive (where the shooting took place) and stopped to admire the view.”

“Mr. Jenks got out of the car and was standing talking to me when suddenly a man walked out of the bushes by the roadside. He was dressed in blue-bib overalls, a blue shirt, and a cap. He had a white handkerchief drawn over his face through which holes were cut.”

The bandit held a gun on the couple and told them to “Stick ‘em up.”

Helen thought the bandit hit Merton over the head with a gun. She said, “I saw Mr. Jenks stagger over the embankment. My first thought was to get help and, as the motor of the car was still running, I moved to the driver’s seat and drove as fast as I could to the first house, where I could get a telephone.”

The detectives listened attentively to Helen’s account of the crime; but they did not entirely buy her story.

When police and deputy coroners searched Merton’s belongings, they found photographs of Helen. One in the back of a gold watch and another in his wallet. In one photo, Helen wore a bathing suit. They also found a telegram postmarked in Santa Monica. It read: “You have been my Valentine for several years.” It was signed “H. S.” Was it from Helen?

The couple clearly had a relationship, and likely parked on the lonely hillside for more than the view. Judging from the newspaper coverage, police weren’t the only ones to doubt Helen’s story. They began reporting the story as a “petting party,” and a “love tryst.”

If you are not familiar with the term, a petting party was a gathering at which couples would hug, kiss, and perhaps fondle each other. Petting did not always stop with a kiss, but it stopped short of intercourse. Popular during the 1920s, and into the 1930s, petting parties outraged the older generation. Which, of course, was the point.

The post-WWI era saw a fundamental shift in the behavior of young adults. The previous generation had to follow strict courtship rules. Modern couples no longer had anyone looking over their shoulders. Three things contributed to the shift. World War I. Cars. Prohibition. The war made cynics and hedonists of many of its young survivors. Cars offered mobility and privacy—a bedroom on wheels. Prohibition normalized law-breaking.

By 1932, when Helen and Merton parked in the hills above Ventura Boulevard, petting parties were passe. But couples of any age who wanted privacy often drove to a remote spot.

Helen’s ever-changing version of events did not help the investigation. In fact, the only part of her story that did not change with each telling was her description of their assailant.

Before he died, Merton told Zeller two people attacked him. But Helen insisted only one man held them up.

Within days of the crime, police brought three suspects, Robert Gilreath, Robert Campbell, and William Saxton, into the station for questioning. They soon released them.

Inspector David Davidson, in charge of the investigation, told reporters they believed the bandit might be one who specifically targeted couples parked in the hills. Following Merton’s refusal to comply with the robber’s demands, the bandit slugged him. When he ran, the bandit shot him in the back. Merton may have been a faithless husband, but he did not deserve to die.

Among his belongings police found Merton had a carry permit, issued by the Sheriff’s Department on September 16, 1931. At the time of issuance, Merton said he needed a gun for “travel protection.” However, having an affair with Helen, may have made him cautious. Perhaps he feared her husband coming after him. However, Norval seemed genuinely surprised that Merton kept photos of Helen, or had a relationship with her.

Was Norval feigning surprise? Detectives could not afford to take him at his word. They investigated and found he spent the afternoon of the shooting in a movie theater.

On Thursday, July 16, the coroner’s jury returned a verdict in Merton’s death, “shot by persons unknown with homicidal intent.”

Helen testified at the inquest. The attractive 30-year-old insisted there was “no lovemaking,” and she and Merton sat in his car “looking at the scenery.” Deputy Coroner Monfort challenged her.

“Now, Mrs. Moffitt, you were never in the rear seat of that car at any time, were you?”

“I never was,” she replied.

“How do you account for the forty-five minutes you spent with Mr. Jenks at this point?”

“Well, we were admiring the scenery, and there was a general discussion about real estate and other topics. I don’t remember all that was said.”

The reason for Monfort’s line of questioning is not clear, although he may have suspected Helen hired someone to kill Merton. It was troubling that Merton said two persons attacked him, and Helen said there was one.

Two weeks after the murder, police searched Helen’s home looking for a weapon. Two hundred yards from where the bandit stood, police found a .32 caliber shell fired from an automatic. Police chemist, Ray Pinker, said he could match the shell to a gun if they found one.

The case stalled. In September, twenty-three-year-old Chester Bartlett surrendered himself to police and confessed he had “done something wrong” in the hills near Mulholland. Bartlett’s confession did not survive scrutiny. He admitted he attempted suicide by swallowing gasoline. The obviously unstable man may have done wrong, but he did not commit murder.

The scant leads dried up, and nobody offered new information, so police had to shelve the Jenks case. It remains unsolved.

What happened on June 14, 1932? Hungry, homeless and without hope, many desperate people roamed the streets of Los Angeles during the Great Depression. Did one of them pick up a gun and attempt to rob Merton and Helen? Did Merton perish at the hands of a would-be robber, or was he the victim of something more sinister?

We can only speculate.

Was her husband cleared? He would be an obvious suspect.

Sam,

Helen’s husband was a suspect. He had an alibi, but not a very good one. He said he was at the movies, then visiting relatives. He is mentioned only briefly in newspaper accounts. I don’t know if police proved his alibi, or if they couldn’t find enough to disprove it.