One thing I love about researching true crime is how a story can change direction. Just when I think I have someone figured out, they do something that seems out of character, and it wipes the smug expression off my face. That happened with Olney Le Blanc.

Olney’s courage impressed me when I discovered his story in newspaper coverage from 1935. He saved his three-year-old son, Bernard, from a man who killed the boy’s puppy and likely had something awful planned for the child.

Curious about where Olney’s life would take him, I continued to search. He appeared in minor news stories about his career as a dancer, and as a teacher. By 1940, he was the recreation leader at McKinley Home for Boys in Van Nuys; a job for which he was well-suited. He lived at the home without his wife or son. Because I could not find documentation, I believe they may have separated or divorced.

I expected Olney to continue his career as a dance teacher. Maybe I’d find he and Annette had divorced. The truth caught me off-guard.

Olney was a killer.

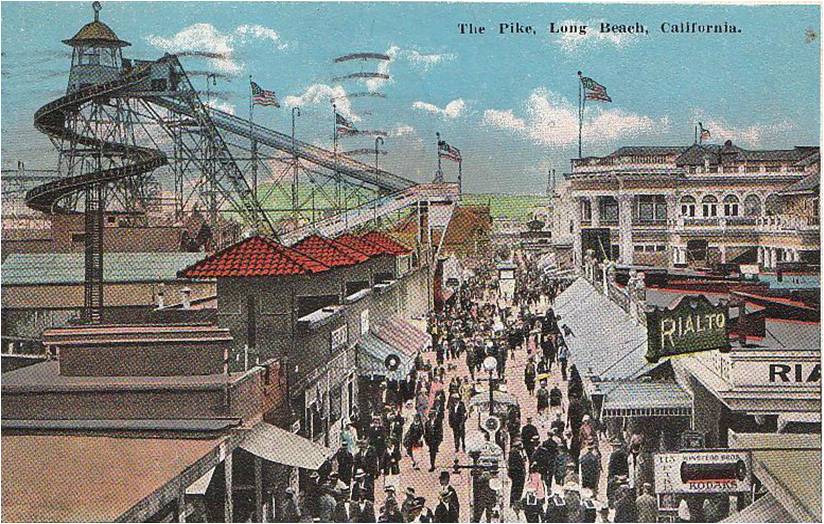

On August 29, 1942, a call summoned Los Angeles County Sheriff’s deputies to the Carmelitos housing project, where someone had stabbed a woman. They arrived at the Carmelitos Housing Project, at the residence of June Dyer, 22-year-old mother of three.

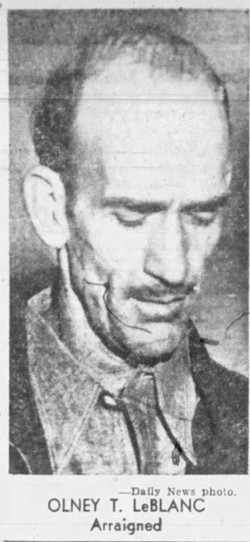

Ten blocks away from the scene of the murder, police found a man unconscious in a car outside a school. Someone also stabbed him. One officer made a tourniquet from the leather thong of his nightstick and stopped blood spurting from a gashed arm. They identified him as Olney Le Blanc, and booked him into the police hospital ward on suspicion of murder.

In one of his pockets they found a letter, written by June.

Dear Donald: This is a written confession of an unforgivable error I made—not in the doing, but because I kept the truth from you. Dan is not your son. You know his father. Hold it not against Danny and love him as you always have if you can.

Donald, I have deceived you many times since the beginning, even telling you I loved you. I lied.

I could never find real happiness with a lie in my heart. Mr. Leblanc has been cheated of a glorified happiness because of me. I’m doing to try to make him happy, as I know he can make me happy and be as grand a father to the boys as anyone in the world. We will work together, something you and I could never get started.

Your wife, June

Why did Olney have June’s letter in his possession?

Working for hours, Sheriff’s deputies Ed Carroll, Emmett Love and H. K. MacVine pieced together the events leading up to the murder.

A witness, 16-year-old Walter Jensen, said he saw June standing beside a car outside of her home, talking to four friends. Another car drove up, its driver called to her, and she left to talk to him.

Walter said, “They seemed to be arguing. Then he grabbed her and threw her to the ground. Walter ran to June’s aid, but the man knocked him down. Her friends carried June into her house. Her husband, Don, arrived home in time to see June die.

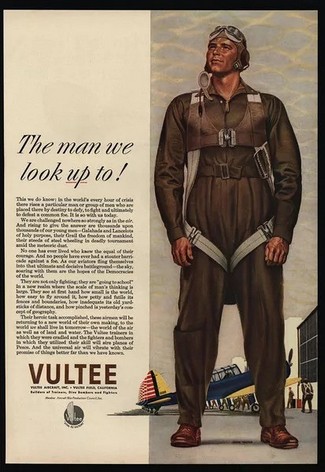

The U.S. was at war, and hundreds of thousands of people moved to Los Angeles for war work at shipyards and factories. June, her husband Donald, and Olney worked at Vultee, a defense plant. June and Olney worked a swing shift, and they got to know each other. When she found out he was a woodworker, she asked if he would give her instruction. Olney agreed.

After her death, newspapers suggested June and Olney were having an affair, and called the case California’s first swing-shift murder. Staggered working hours sometimes made it difficult for spouses not to stray.

Donald took umbrage with newspapers that suggested June had broken her marriage vows. He said Olney became obsessed with June. In fact, six weeks before the murder, Olney kidnapped June, drove her to the Mojave Desert, stabbed her in the side and forced her to write a letter to Don, confessing infidelity.

Sheriff’s records proved the truth of Don’s statement. Deputies took Olney into custody and booked on suspicion of assault with a deadly weapon following the kidnapping. June and Don refused to press charges.

At the time of the kidnapping, Olney told officers, “I was so madly in love with her I didn’t know what I was doing.”

The letter found on Olney following his attempted suicide was the letter he had forced June to write.

Olney appeared for his preliminary hearing on September 15th. The judge remanded him to the County Jail without bail, pending trial, on a charge of murder.

As deputies led a shackled Olney from the courtroom, Don lunged at him, screaming, “I hope you die in a thousand hells—you didn’t have the guts to kill yourself, but you could kill June.” A bailiff shoved Don aside before he could get his hands on Olney.

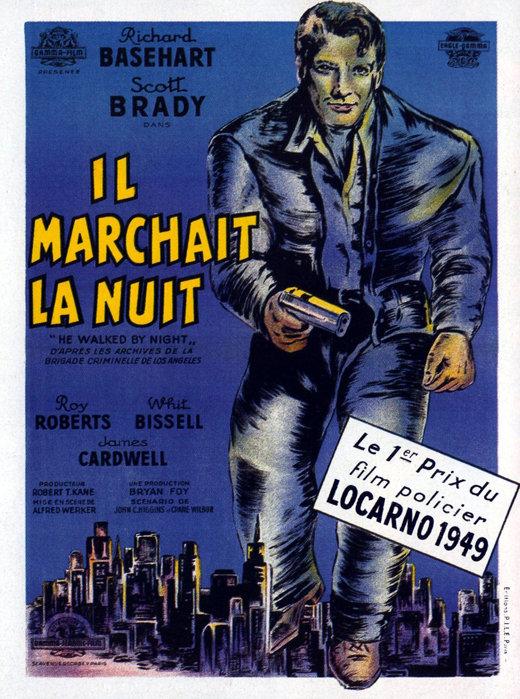

In October, Olney entered a plea of not guilty by reason of insanity. The court appointed three alienists to examine Olney, and set trial for November 6 before Superior Judge Charles W. Fricke.

I’ve written about Fricke before. He was a no-nonsense jurist; some even called him a “hanging judge.” Olney was in for a rough ride.

In a surprise move, under an agreement with the D.A.’s office, Olney’s not guilty plea would stand. No witnesses would be called before Judge Fricke, who would use a transcript of the preliminary hearing and to have the court consider it as the evidence in determining Olney’s guilt or innocence, and the punishment if any.

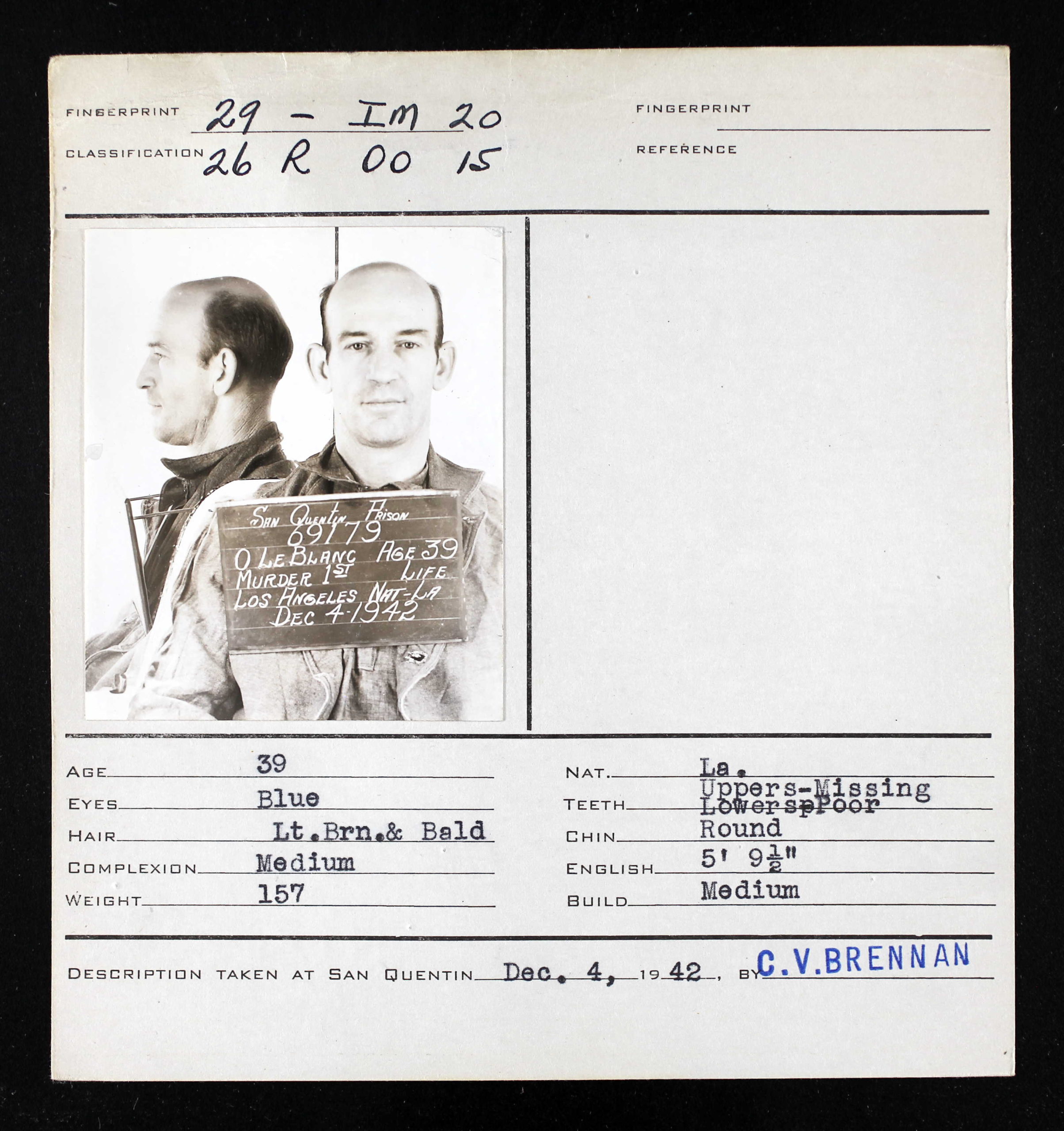

On November 23rd, Judge Fricke found Olney guilty of first-degree murder, and sentenced him to life imprisonment.

Why did Olney’s life unravel? When I first found his story, it seemed he would lead a happy and productive life. How did he go from saving his son from a kidnapper to murdering June with a German sword?

I accept I will never know.