Murder victims lose their identities. They are a toe tag in the morgue; they are a file number for police. Sometimes it is easy to forget that they were much more than a newspaper headline.

Born in a small New Mexico town in 1902, Jeanne Axford came of age during the Roaring ‘20s. Perfect timing for the free-spirited girl. She married at 17 to David Wrather and they had a son, David, Jr.

In 1922, after training in New Mexico, Jeanne worked as a nurse in Amarillo, Texas. Marriage didn’t suit her. She and David divorced in 1924; she won custody of their son.

In 1925, Jeanne married again. That marriage, too, failed. Rumor has it Jeanne acted in films, but I couldn’t find her listed in the Internet Movie Database, even under an alias, so she may have had uncredited roles.

Regardless of whether she appeared in movies, Jeanne had an interesting Hollywood connection. She worked as a private nurse for Marion Benda Wilson, Rudolph Valentino’s last date, and maybe his last love. Known as the “Woman in Black” for many years, Marion put flowers on Valentino’s grave.

Sometime between 1925 and 1931, Jeanne learned to fly and earned the moniker, “Flying Nurse.” She worked for a large oil company in South America, flying from one oil field to another, caring for workers. She became a member of the Women’s Air Reserve, and the 99 Club, an organization of women aviators.

Either an optimist, or a glutton for punishment, Jeanne married for a third time in Dallas, Texas on October 8, 1931, two days after her 29th birthday, to Curtis Bower. It took the couple five weeks to realize their mistake. Dissolving her marriage earned Jeanne another nickname, “air-mail divorcee.” The divorce papers, prepared by her attorney, Allan Lund, went via air to Juarez, Mexico for filing. A law firm in Mexico provided for a final decree by proxy. Neither Jeanne nor Curtis needed to appear in court.

On July 5, 1932, Jeanne’s mother, Oma Randolph, went to police to file a missing person report. Jeanne left home the morning of June 27 to drive to the Mexican border, where she planned to board a private plane for Mexico City.

The week following the missing person report, Jeanne cabled her mother from Mexico City. “I can’t understand the worry I have caused in the United States by flying to Mexico. I am flying back for the Olympics. I assure everyone that I am okeh.”

Jeanne kept a low profile for the next several years. She married in 1944 for the fourth and final time to a former Marine, Frank French.

It isn’t clear when Jeanne started her slide into alcoholism, but by the mid-1940s, she fought demons she could not control.

Alcohol fueled a life of risky behavior and made Jeanne easy prey for a monster.

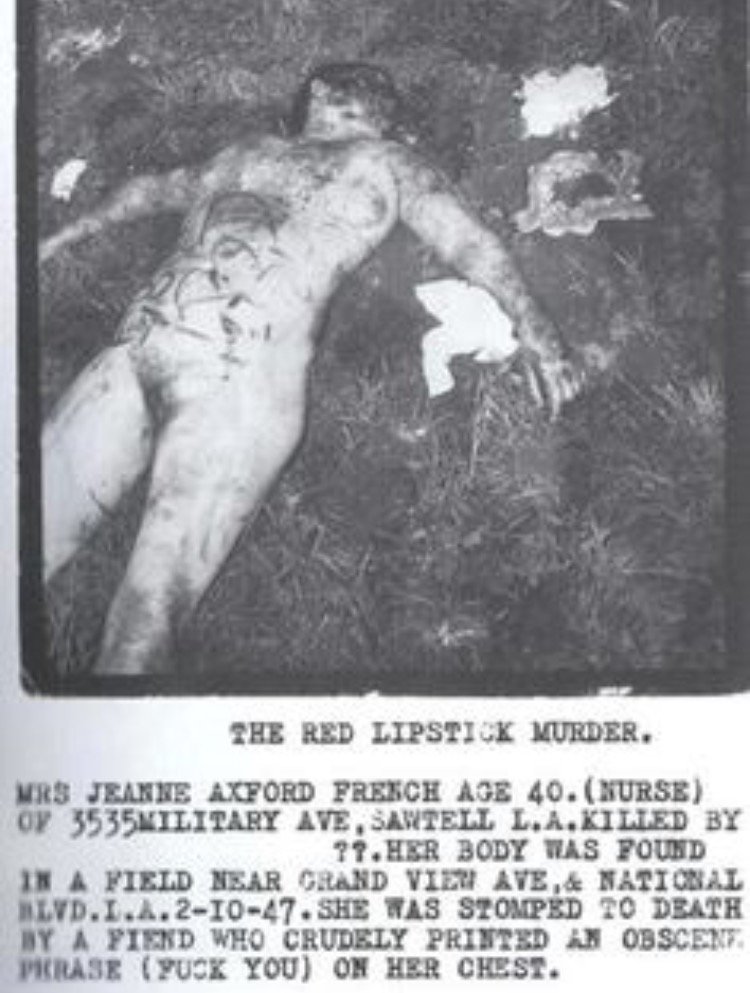

On February 10, 1947, less than a month after housewife Betty Bersinger found Elizabeth Short’s bisected body in a Leimert Park vacant lot, Hugh C. Shelby, a bulldozer operator, found the brutally beaten, nude body of a woman in a field near the Santa Monica Airport. The Herald put out an extra edition with the headline: “Werewolf Strikes Again! Kills L.A. Woman, Writes B.D. on Body.”

Within a couple of hours, police identified the victim as forty-five-year-old Jeanne French.

Jeanne suffered blows to her head, administered by a metal blunt instrument—a socket wrench. As bad as they were, the blows to her head were not fatal. Jeanne died from hemorrhage and shock due to fractured ribs and multiple injuries caused by her killer stomping on her. Her chest bore heel prints. It took a long time for Jeanne to die. The coroner said that she bled to death.

Mercifully, Jeanne was unconscious after the first blows to her head so she never saw her killer take the deep red lipstick from her purse, and she didn’t feel the pressure of his improvised pen as he wrote on her torso: “Fuck You, B.D.” and “Tex.” Police looked for a connection between Jeanne’s murder and Elizabeth Short’s death; but they found nothing.

Jeanne was last seen seated at the first stool nearest entering the Pan American Bar on West Washington Place. The bartender told police Jeanne sat next to a smallish man with a dark complexion sat on the stool next to her. The bartender assumed they were a couple because he saw them leave together at closing time.

On the night before she died, Jeanne visited Frank at his apartment and they’d quarreled. Frank said Jeanne, who was drunk, started the fight, then hit him with her purse and left.

Jeanne’s twenty-five-year-old son, David, came in for questioning. As he left the police station, he saw his step-father for the first time since he’d learned of his mother’s death. David confronted Frank and said: “Well, I’ve told them the truth. If you’re guilty, there’s a God in heaven who will take care of you.” Frank didn’t hesitate. He looked at David and said: “I swear to God; I didn’t kill her.”

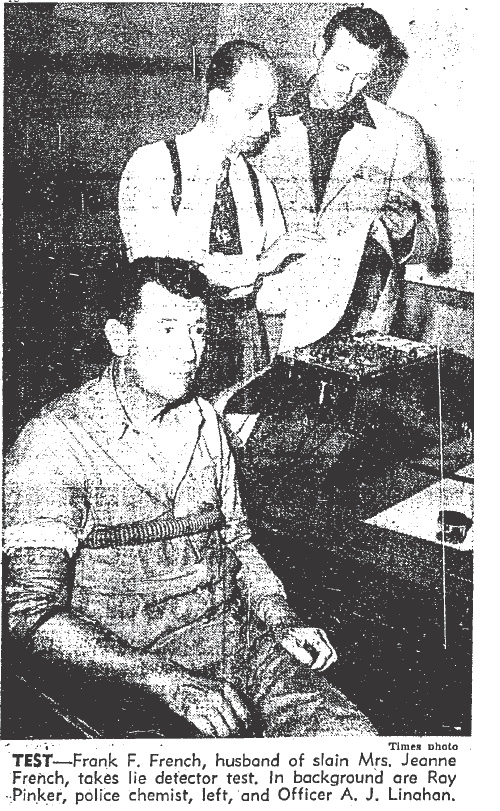

Police booked Frank for murder, then they cleared him. His landlady told police she could verify Frank was in his apartment at the time of the murder. His shoe prints failed to match those found at the scene of the crime.

Cops had few leads. They found French’s cut-down 1929 Ford roadster in the parking lot of a drive-in restaurant, The Piccadilly at Washington Place and Sepulveda Blvd. Witnesses said that the car was there at 3:15 on the morning of the murder, and a night watchman saw a man leave it there. The police never accounted for Jeanne’s whereabouts between 3:15 a.m. and the time of her death, which the coroner estimated to be around 6 a.m.

Police rousted scores of sex degenerates, but they eliminated each as a suspect. Officers also checked out local Chinese restaurants after the autopsy revealed that Jeanne ate a Chinese meal before her death.

Jeanne’s slaying became known as the “Red Lipstick Murder” case. Like the Black Dahlia case, it went cold.

Three years later, following a Grand Jury investigation into the many unsolved murders of women in L.A., the District Attorney assigned investigators from his office to look into the case.

Frank Jemison and Walter Morgan worked on Jeanne’s murder for eight months, but they never closed it. They came up with one hot suspect, a painter who worked for the French’s four months prior to the murder. He said he dated Jeanne several times. The cops discovered the painter burned several pairs of his shoes—he wore the same size as the ones that left marks on Jeanne’s body. He seemed a likely suspect until he didn’t. Police cleared him despite his odd behavior.

The 1940s’ high number of unsolved female homicides prompted a 1949 Grand Jury investigation into police inaction.

Like the murder of Elizabeth Short, there have been no leads in Jeanne French’s case in decades. Two more names added to the list of unsolved homicides of women during the 1940s.