Tracy Leroy Nute, alleged teenage victim of Professor Max Bernard Franc’s “homosexual rage”, was described by his mother, Judy Nute, as a “sentimental” and “naive” kid with problems. Interviewed in her Kansas home she said that her son had been in trouble with the law, “but nothing that any rowdy teenager wouldn’t have gotten into.”

Tracy’s scrapes with the law may have been minor, but at some point Judy found it impossible to handle him and he spent much of his time in juvenile homes. The homes in which he was placed didn’t work out and he decided, like many unhappy kids, to head for Southern California. His destination was Hollywood where he intended to become an actor. Runaways have been coming to Hollywood in droves with the same dream since the first studios appeared in the 1910s. But big dreams die hard and fast when the reality of street life sets in–everything is a struggle–food, cigarettes, a place to crash. Tracy, like other teenage transplants before him, was most likely welcomed to town by drug dealers and pimps, not an agent with a movie contract. Tracy’s home state’s motto is Ad Astra per Aspera (To the Stars through Difficulties). He never reached a star, he never had the chance. By the spring of 1987 he was turning tricks, and by summer he was dead.

Max contended that he wasn’t Tracy’s killer and that the murder had been committed by a gay prostitute by the name of Terry Adams. According to Max, Terry had even lived with him for a while in Fresno. Did Terry exist? Sheriff’s investigators never found him; and Max was so terrified of being outed that he’d gone to great lengths to conduct a secret life in Hollywood. Would he have risked everything to bring a lover to Fresno? It is doubtful.

The trial was as interesting as had been anticipated. Rumors circulated that Tracy had attempted to extort money from Max. If true the kid had morphed quickly from a naive Kansas runaway to a street-wise Hollywood blackmailer.

Public Defender, Mark Kaiserman, admitted that Max was a voyeur who suffered from poor judgment. Explicit photos of the victim were found among the hundreds discovered in Max’s apartment. Interestingly, no photos of his alleged lover were found. The attorney unveiled a unique defense which was based primarily on Max’s ineptitude. Kaiserman argued that Max was too “nerdy” and too much of “a klutz” to wield handle a gun, let alone manage a chain saw. Kaiserman reminded jurors that Max had cemented over the entire yard at his Fresno home to avoid using a lawn mower.

![]()

Was it a creative defense? Without a doubt. Was it an effective defense? Unfortunately for Max, no. He was found guilty of Tracy’s murder. Fear of exposure, if that was the motive for the slaying, easily explained how Max was able to overcome his nerdiness and commit such an atrocious murder.

The jury accepted the prosecution’s case that characterized the defendant as a man overcome by homosexual rage and rejected the defense argument that Max was too wimpy to have committed the crime.

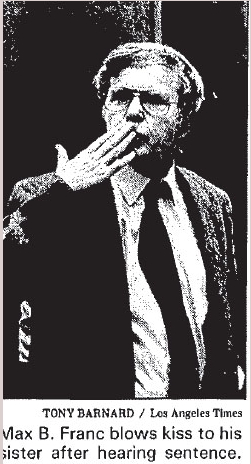

At his sentencing hearing Max’s sister, Carol Waiters, a psychiatric social worker from Philadelphia, made a plea for leniency on her brother’s behalf. She implored Judge John H. Reid to consider “the whole person” rather than the part of his personality that drove him to murder. On July 28, 1988, Judge Reid sentenced Max to from 25 years to life with the possibility of parole in 17 years.

Max didn’t live long enough to become eligible for parole. He died of a heart attack in Cochran State Prison on September 18, 1997.