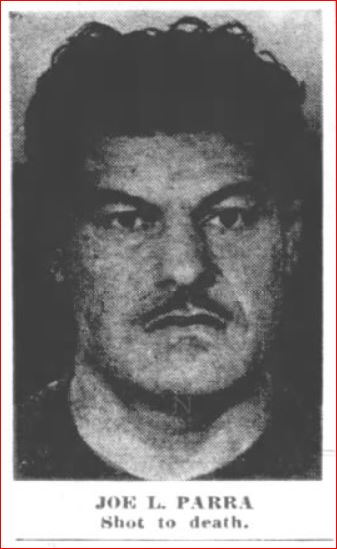

In 1952, LAPD Policewoman Florence Coberly had a bright future in law enforcement. She helped take down a career sex criminal, Joe Parra, in a treacherous sting operation.

Florence stayed tough during the inquest following Parra’s shooting—even when his brother Ysmael shouted and lunged at photographers. She appeared on television and received honors at awards banquets all over town.

After three years of marriage, she divorced her husband Frank in 1955. We’ve heard countless times how tough it is to be a cop’s wife, but I imagine being the husband of a cop is not any easier. The unpredictable hours and the danger can be enough to send any spouse out the door forever.

We don’t really know what caused the Coberly’s marriage to dissolve. The divorce notice appeared in the June 29, 1955 edition of the L.A. Times, but it was legal information only and gave no hint of the personal issues which may have caused the couple to break up.

[Photo courtesy of USC Digital Archive]

With no further mention of Florence in the Times for several years, we can assume that her career was on track. Then, nearly six years after the Parra incident, on July 2, 1958, the Times ran a piece buried in the back pages of the “B” section under the headline: Policewoman’s Mother Convicted of Shoplifting.

A jury of eleven women and one man found Mrs. Gertrude Klearman, Florence’s fifty-three-year-old mother, guilty of shoplifting. It is embarrassing to have your mom convicted of shoplifting, and it is worse if you are in law enforcement. But it is orders of magnitude more humiliating if you are a police officer busted WITH your mother for shoplifting.

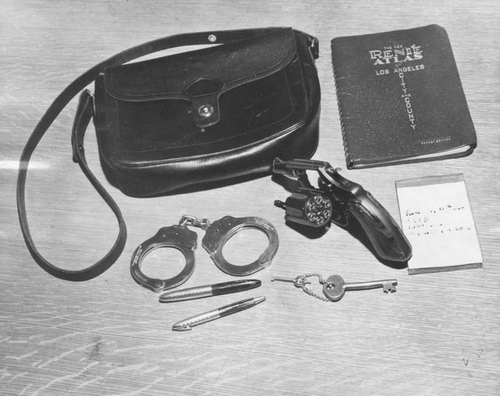

According to George Sellinger, an off-duty police officer working as a store detective to supplement his income, Florence and her mother stole two packages of knockwurst, a can of coffee, a package of wieners and an avocado–$2.22 worth of merchandise. The accusation could destroy Florence’s career.

[Photo courtesy USC Digital Archive]

At her misdemeanor trial Florence’s attorney, Frank Rothman, vigorously questioned Sellinger and got him to admit that he had not actually seen Florence stuff the food items into her purse. He pressured her to submit to a search outside the grocery store based on the scant evidence seeing her with packages in her hand. Rothman made the case for illegal search and Florence got off on the technicality.

LAPD in the late 1950s was touchy about any hint of scandal or misbehavior by its officers. During the decades prior to William H. Parker’s ascension to Chief, the institution watched as some of their number went to prison for graft and corruption.

While a package of knockwurst hardly rises to the standard of unacceptable behavior that had plagued LAPD earlier, just being arrested was enough to get Florence suspended from duty pending a Police Board of Rights hearing.

It couldn’t have been easy for Florence to sit on the sidelines and await the decision. Law enforcement wasn’t a 9-5 job for her, it was a career and one for which she had displayed an aptitude.

While Florence waited on tenterhooks for the Board of Rights hearing, her mother received either forty days in jail or a $200 fine (she paid the fine).

Florence’s hearing began on July 22, 1958, before a board composed of Thad Brown, chief of detectives, and Capts. John Smyre and Chester Welch. Even though a civilian court of law exonerated Florence, the board found her guilty and ordered her dismissed from LAPD.

It was an ignominious end to a promising career, and I can’t help but wonder if there was more to Florence’s dismissal from the police force than the shoplifting charge.

In February 1959, Florence sued in superior court, seeking to be reinstated. She directed her complaint against Chief Parker and the Board of Rights Commission.

Florence denied her guilt in the shoplifting charge. She contended that the evidence applied only to her mother.

It took several months, but in July 1959 Superior Court Judge Ellsworth Meyer sided with the LAPD and refused to compel Chief Parker to reinstate Florence.

I salute Florence for her no-holds-barred, kick-ass entry into policing in 1952; and I would be remiss if I didn’t mention one last time that fantastic bandolier that dangled from her belt. I maintain my position that women police officers know how to accessorize.

If you want to know more about Florence, a reader kindly sent me a link to this LAPD press release.

MANY THANKS to my friend and frequent partner in historic crime, Mike Fratantoni. He knows the BEST stories.

NOTE: This is an update and revision of a previous post.

I would have made an exception and given her a pass for the knockwurst. She was a valuable officer and this just does not make sense.

On another subject, have you ever written about that donut shop on South Main where the transvestites threw donuts at the cops? I think it was in the late 50s.

I’m with you. The knockwurst caper doesn’t rise to the level of serious misconduct as far as I’m concerned. I wonder if internal politics played a part.

What? Transpeople hurling donuts at cops? Donut hurling strikes a familar chord, but the rest of it does not. I must find this story!

Thanks, Gary!

Joan