Happy New Year!

The holidays aren’t joyful for everyone. Family gatherings, liquor, and year-long grudges can combust over anything—from the TV remote to the last slice of pie. Holiday homicides often boil down to too much booze and too much togetherness.

For the Thorpes, the trigger wasn’t a turkey leg or a slice of pie—it was the uninvited arrival of an ex-husband.

On Thanksgiving evening, November 27, 1952, Seal Beach officers rolled to 131 6th Street after a call from Frances Conant Thorpe. She told police that her ex-husband, Al McNutt, had stopped by to offer holiday greetings to her and her current husband of eight months, Herman. Frances and Herman had been drinking and arguing all day. McNutt’s appearance pushed things over the edge. A struggle followed, and Herman wound up dead.

Frances offered three incompatible versions of the shooting.

First, she told Officer William Dowdy that Herman had committed suicide.

Then, she told Deputy Coroner Walter Fox that she shot him twice during a scuffle.

Finally, she told District Attorney Investigator M.D. Williams that Herman had tried to shoot her; she fell, hit her head on a case of root beer, blacked out for hours, and awoke to find him dead on the bedroom floor.

The facts shredded all three stories.

Herman’s autopsy revealed nothing consistent with suicide. The position of the weapon beneath his body and the trajectory of the fatal chest wound made self-infliction impossible. There was no gunshot residue on his hands and no powder burns on his skin. But there were traces of gunpowder on Frances’ bathrobe and on her left hand.

Investigator Williams noted that Frances’ attitude was evasive, and her stories “didn’t hold together.”

Dr. Raymond Brandt’s autopsy established Herman’s time of death as 1:30 p.m.—a full hour earlier than Frances claimed. Doctors dismissed her blackout story outright. One said it would be “medically impossible to be blacked out so long, even if she was intoxicated.”

The jury rejected her stories, too. After six hours and twenty-eight minutes of deliberation, they found Frances guilty of manslaughter. She was sentenced to up to ten years in prison.

Thanksgiving in Seal Beach didn’t end with dessert—it ended with a revolver, a bad lie, and a dead husband.

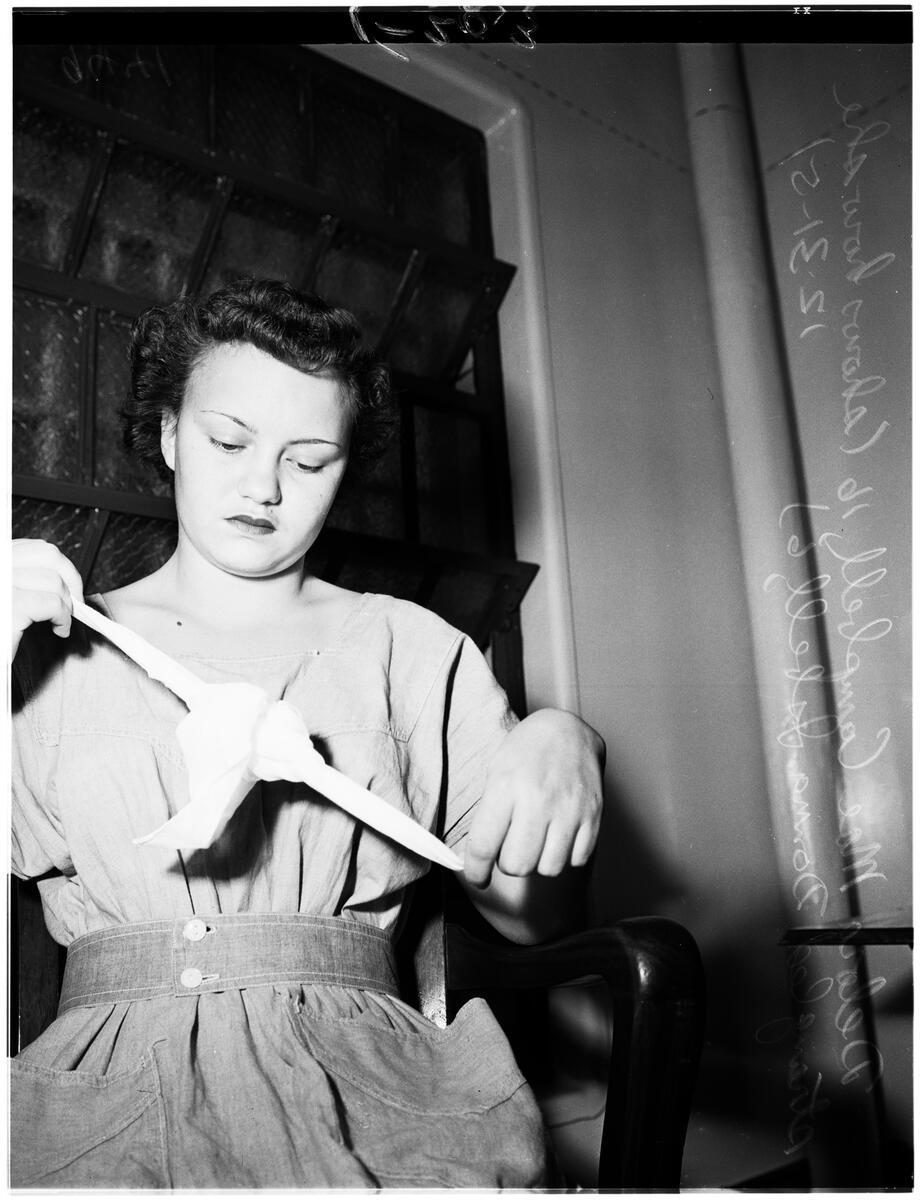

Delora Mae Campbell didn’t cry, tremble, or ask for her parents when accused of strangling six-year-old Donna Isbell. She just stood there.

Pending her hearing, authorities held her in isolation in the County Jail rather than Juvenile Hall. Sgt. Frances Cardiff, a jail matron, reported that Delora slept eight hours straight and woke at 5 a.m. on December 31st, quiet and indifferent to both her surroundings and the killing.

When reporters pressed her, Delora couldn’t—or wouldn’t—explain the impulse she claimed had driven her. Maybe it was a vision. Maybe she acted knowingly. “I could have been awake and actually aware of what I was doing,” she said. “I’m not sure.” Asked if she would strangle Donna again, she answered the same way: “I’m not sure.” She said she liked Donna and her older brother, Roy.

What, then, made her do it?

Donna’s parents struggled with their loss, and with a smaller heartbreak of their own. They couldn’t afford the doll Donna wanted so badly for Christmas, but they’d told her Santa would bring it for her February birthday. After the murder, a Marine, Sgt. William Thornton, and his wife, Paula, read about the unfulfilled promise and bought the doll themselves. The Isbells buried it with Donna.

Delora’s father, Clem Campbell, a truck driver from Fort Lupton, Colorado, visited her in County Jail. “We could hardly believe it,” he said. “I guess it was one of those things that just had to happen.” A strange remark from a father whose child had killed another. Not just a strange remark, but a potential window into a family culture of emotional dislocation, which may echo in Delora’s flat affect and her own comment: “I’m not sure.”

Dr. Marcus Crahan submitted a psychiatric report declaring Delora legally sane. Had he found her insane, she might have avoided adult prosecution; instead, she was nudged toward it.

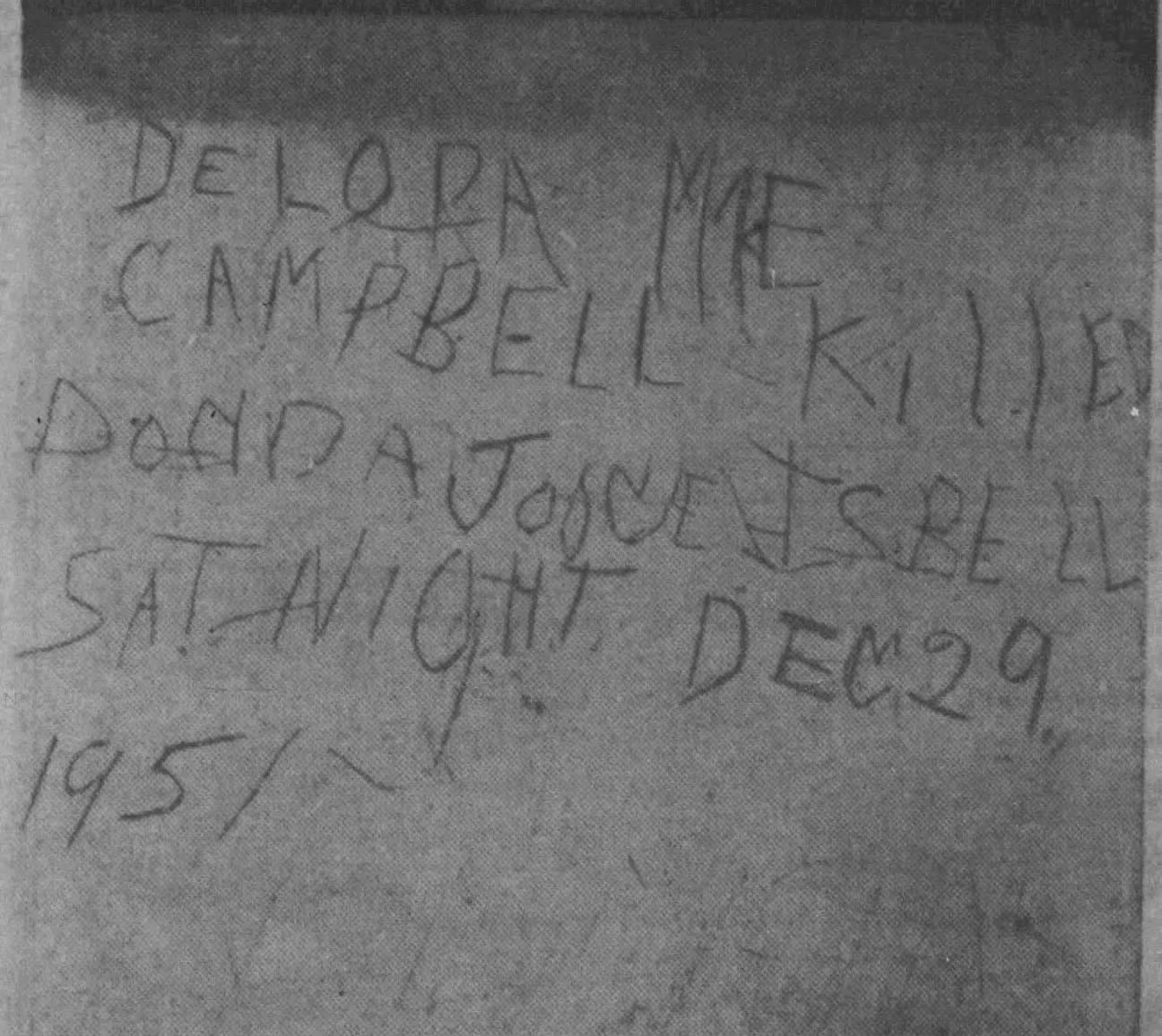

At the coroner’s inquest, Delora took the stand only long enough to say that, on advice of counsel, she would not testify. She didn’t need to. During her isolation, she took a bobby pin and scratched a confession into the enamel of her face-powder compact. No one heard the faint scrape of metal on metal as she wrote:

“DELORA MAE CAMPBELL KILLED DONNA JOYCE ISBELL SATURDAY NIGHT, DEC. 29, 1951.”

Sheriff’s Capt. William Barron asked what prompted her to carve the inscription. “Things got to bothering me a lot,” she said. “I couldn’t talk to anyone, and I felt satisfied about writing—the same as if I talked about it to someone.”

A coroner’s jury found Donna’s death homicidal and Delora probably criminally responsible. The court ordered her to Camarillo State Hospital for a 90-day observation. Afterward, Clem petitioned to have her declared insane and in need of continued care. Two court psychiatrists agreed she was mentally depressed and showed signs of a “disturbed family relationship” and “emotional illness,” but believed she might improve with treatment.

In the early 1950s, psychiatric care for juvenile girls leaned heavily on Freudian interpretation and moral rehabilitation, supported by sedatives and occupational therapy. Whatever treatment Delora received, she followed the rules, and was rewarded with small perks.

Nobody heard anything more about her until April 1954, when she walked away from the hospital. She’d been trusted with grounds privileges for months. With about $70 earned from hospital work, she traveled by bus to Bakersfield, wandered for a few days, then grew tired of “being a fugitive.” She contacted her aunt and uncle in Long Beach—the same relatives she lived with at the time of the murder. They offered to pick her up. When she stepped off the bus at the designated spot, Los Angeles County Sheriff’s deputies were waiting. They returned her to Camarillo.

Sometime in 1956, Delora was quietly released. She returned to Colorado, married twice, had two children, and—so far as anyone can tell—never reoffended. She led a normal life.

Her case leaves behind more questions than answers. No one ever determined what tipped her into violence that December night. In photos, she often appears older than her years—haunted, guarded, carrying something she never named. It’s only an impression, but sometimes an impression is all a case like this leaves.

In the 1940s and 1950s, adolescent girls who committed serious violence often came from chaotic or emotionally barren homes, or from environments marked by humiliation, neglect, or unspoken harm. Whether Delora carried any of that with her is impossible to say. The official record confirms no abuse. It doesn’t rule it out.

Whatever drove her—trauma, dissociation, rage with no safe outlet—remains locked in the silence she maintained after her confession on the compact.

Donna was buried with the doll she longed for. Delora carried only her compact. Between them lies a single moment she called an impulse—irresistible or otherwise—and the truth of it went with her.

NOTE: This narrative draws on newspaper archives, court transcripts, and mid-century psychiatric evaluations. The official record of Delora Campbell is thin, fractured, and filtered through the lens of 1950s ideas about girls, crime, and mental disturbance. I’ve followed the trail where it leads and respected the silences where it stops. In a case built on impulse and uncertainty, the gaps are part of the truth.

Photographs are from the USC Digital Library. Los Angeles Examiner Photographs Collection

In the grip of an irresistible impulse, Delora saw a girl laid out like a doll, arms crossed, a green necktie cinched tight. The girl in the vision, six-year-old Donna Isbell, slept in the next room. Her eight-year-old brother Roy Jr., was asleep nearby. Their parents, Roy Sr., a petty officer at Los Alamitos Naval Station, and Garnett, who worked nights at Douglas Aircraft, weren’t home.

Unable to find a green necktie, Delora took one of Mr. Isbell’s black socks. That would have to do. She tore the sheet from Donna’s bed, stuffed a corner into the girl’s mouth, then wound the sock around her neck and pulled.

Donna didn’t cry out. She lifted her arms once, then went still.

Delora waited, then pulled again.

Roy, asleep just feet away, didn’t stir.

Delora obeyed the impulse that had tormented her for a long time. Maybe now it would end.

She sat on the living room sofa and lit a cigarette. The smoke steadied her for a moment, then the fear crept in—cold and absolute. She couldn’t explain what she had done—not even to herself.

She walked barefoot to the house next door and knocked. No answer. A few doors down, she found Dr. Sidney G. Willner. “Something’s wrong… at the house. Come with me,” she said. Then, almost to herself: “I must have done it. There was no one else there.”

They walked in silence. Dr. Willner wondered what she meant. Even if she had told him, nothing could have prepared him for what he found.

Dr. Willner called the Sheriff’s Department.

Deputies took Delora to the nearest substation for questioning. Because Delora was a teenage girl, the department brought in Detective Sergeant Lena Barner to assist Captain J.M. Burns with the questioning.

As investigators questioned the high school sophomore, they noticed her emotional distance. Sergeant Barner said when she asked Delora why she did it, “She just sat there and stared.”

The only times she showed emotion were when she saw Donna’s body at the scene and when Roy and Garnett Isbell entered the substation. Roy and Garnett were devastated.

Delora babysat Donna and Roy, Jr. several times before the murder, and she and the children got along well. The family had no reason to fear her.

As Donna’s parents tried to process their grief, Delora answered investigators’ questions.

She said quietly, “I often felt like strangling my brothers and sisters.”

She harbored violent impulses toward her siblings for a long time. Her feelings, coupled with her constant fights with her mother, were the reasons she was allowed to move from Colorado to Southern California two years earlier.

Women and girls rarely commit murder—especially in 1951. The story made headlines across the country. It was horrifying. And strange.

Was it a movie? A psychotic break? Something older and darker inside her? Could someone commit such a brutal act… and not be evil?

NEXT TIME: Wrapping up Delora’s story.

Photographs courtesy USC Digital Library. Los Angeles Examiner Photographs Collection

In Fort Lupton, Colorado, a fight with your mother could end in grounding. For Delora Campbell, it ended in something far darker. Life in post-war Fort Lupton revolved around church socials, 4-H clubs, and county fairs. Residents followed high school football with a passion, and the Fort Lupton Blue Devils were a source of pride. When the Blue Devils partied under the watchful eyes of adults, they danced to Patti Page’s soulful rendition of The Tennessee Waltz, or did a lively country swing to Hank Williams’ Lovesick Blues.

In the 1950s, no matter where she lived, girls had to adhere to a strict code of behavior. Delora didn’t just test boundaries — she unsettled people. According to her parents, Clem and Francis, they sometimes feared she might harm her siblings. Their fear went beyond the usual sibling squabbles — it sounded like a warning.

Was the pressure to conform to community standards too much for Delora? Or maybe it was one fight too many with her mother, or another battle with her younger brother, Dickie. Maybe she feared she would act on an impulse to harm a family member. Whatever her reasons, at fourteen she ran away from home for the first time.

The court intervened, and a juvenile judge placed her on probation.

Delora’s behavior alarmed everyone — from her parents to school authorities and local pastors. Even her peers may have found her behavior unsettling. One of the biggest fears for a girl Delora’s age was getting a reputation. No worse fate could befall her.

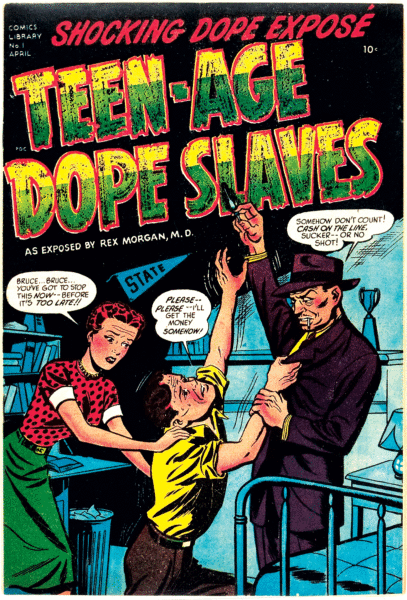

In postwar America, the specter of juvenile delinquency haunted dinner tables from coast to coast. It wasn’t the commie down the street that frightened people; it was their own kid — sulking in the next room, listening to Hank Williams, and thinking dark thoughts.

Historically, when teenage boys acted out, their activities were met with a nod and a wink — the old “boys will be boys” trope. If they committed a serious crime, they might be labeled thugs or delinquents, and could end up in juvenile hall.

Girls faced a different kind of judgment. If they failed to measure up, they weren’t rebellious; they were hysterical, or morally compromised. Moral panic, a genuine fear in the 1950s, punished girls differently. Did Delora worry she might face serious punishment as had other girls who stepped outside expected norms? A girl who rebelled might not go to jail, but to a mental institution — until her hormones, doctors hoped, burned out the madness. Such a girl could count herself lucky if she was released without lasting damage from electroconvulsive therapy, heavy sedation, or ice baths. The belief that emotional instability was baked into the female brain dated back millennia. As one modern paper put it: “Hysteria is undoubtedly the first mental disorder attributable to women…”

Whatever was going on in Delora’s life, something caused her to run again. Was she concerned that she would harm herself or someone else? This time, she vanished for three weeks. Not knowing what else to do, her family sent her to live with her aunt and uncle in Long Beach, California. They may have wanted to spare her local infamy and give her a fresh start — or simply chose to quiet wagging small-town tongues.

The whispers in a small town can kill you.

On the surface, Delora appeared to thrive in her new environment. But was she genuinely happy, or just adapting to survive? On September 1, 1950, the Long Beach Press-Telegram listed her among a group of young people who attended a barbecue dinner where they played games and square danced.

Delora wrote home to tell her parents how much she enjoyed living in Long Beach and going to Woodrow Wilson High School. Francis was surprised — her daughter had never liked school in Fort Lupton.

Delora may have received an allowance, but sometimes when a girl needed extra cash, she took a job babysitting. For several weeks at the end of 1951, she babysat for six-year-old Donna Isbell and her eight-year-old brother, Roy.

On December 29, 1951, Delora walked a few blocks from her aunt and uncle’s home to the Isbell’s to sit with the kids. After the children went to bed, she stretched out on the sofa to watch television. The flickering light filled the room as she watched the 1947 film Repeat Performance.

The movie told the story of a Broadway actress who murders her husband on New Year’s Eve, 1946. As she’s leaving the crime scene, she wishes she could turn back the clock and do the year over — and suddenly finds herself transported to New Year’s Day, 1946.

Delora watched the film to its end, a little after 11 p.m. The house was still.; Donna and Roy were asleep. For a moment, Delora sat and reflected on the film she had watched.

Then the strangest thing happened. She had a vision in which she saw herself committing murder. The vision wasn’t terrifying — it was familiar. She had often felt like choking the life out of her siblings when she lived with her family in Fort Lupton, but she had resisted.

On this night, something inside her felt different—out of her control. She felt the tug of an irresistible impulse guide her as she calmly walked toward six-year-old Donna, sleeping snug in her bed. But first, she needed a necktie.

NEXT TIME: Can Delora resist her impulse?

Welcome! The lobby of the Deranged L.A. Crimes theater is open! Grab a bucket of popcorn, some Milk Duds and a Coke and find a seat. Tonight’s feature is WITHOUT WARNING, starring Adam Williams, Meg Randall, and Edward Binns.

The movie is entertaining, but it is the Los Angeles locations that make it worth watching. Below are a few you should look for. Enjoy the movie!

IMDB says

Carl Martin is a morose and deranged Los Angeles gardener, who, in retribution for the infidelity of his unfaithful wife, sets about to kill as many blondes as he can. From the time the film opens, to the sound of a radio turned up full-blast over the still-warm corpse of a blonde, the audience knows the identity of the killer. The film depicts, with documentary realism (as it was shot on location in and around Los Angeles), how the police, using laboratory techniques against the few clues they have, track down Martin.

LOS ANGELES LOCATIONS:

Carl’s hilltop home., overlooking the freeway and Los Angeles skyline.

Union Station – 800 N. Alameda Street, Downtown, Los Angeles, California, USA

(Carl Martin catches a taxi to Union Station

New Follies Theater – 548 S. Main Street, Los Angeles, California, USA

(Carl Martin in front of theatre, demolished)

Continental Club & Restaurant – 1508 N Vermont Ave, East Hollywood, Los Angeles, California, USA

(Carl Martin meets woman in parking lot, demolished)

Los Angeles River, California, USA

(police, dead woman)

Four Level Interchange – Downtown, Los Angeles, California, USA

(Foot pursuit of freeway interchange. Officially the Bill Keene Memorial Interchange, this is the four level Interchange of Arroyo Seco Parkway, Harbor Freeway, Santa Ana Freeway and Hollywood Freeway. Completed in 1949 and fully opened in 1953 at the northern edge of Downtown Los Angeles)

East 7th Street and Alameda Street, Los Angeles, California, USA

(Produce market scenes.)

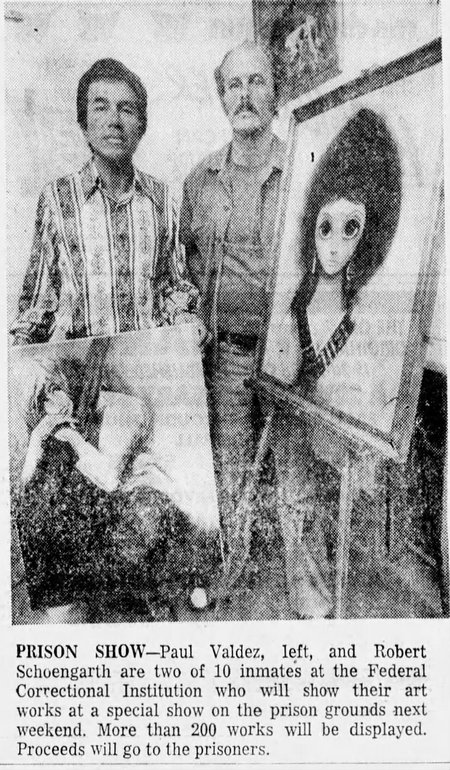

At 20-years-old, Robert Schoengarth could have kicked heroin and started over. But heroin is a hard habit to break. Heroin attaches to opioid receptors in the brain and nervous system, like natural endorphins, so the brain adapts with regular use. Getting clean isn’t a matter of willpower. You are fighting your altered chemistry. Withdrawal from heroin, while not often life-threatening, can be so painful you pray for death.

In September 1957, Robert married June Leach in Las Vegas. They had a daughter, but the marriage didn’t last. We can only speculate about what drove them apart.

From the time he was a teenager, Robert moved between California and Colorado. He had trouble with the law in both places.

In January 1963, an anonymous tip alerted the LAPD’s Hollywood division that Colorado wanted Robert for felony robbery and theft. They busted him near Klump Avenue and La Maida Street in North Hollywood. 6

Robert confessed to stealing from a Ventura Boulevard business after his arrest for suspected burglary. He had drugs on him—a vial with 45 pink pills in it. He told officers he came to North Hollywood to score dope.

Robert’s brother, William, had his own problems. In 1956, Burbank police arrested William and two other men for burglarizing an Apple Valley men’s clothing store on New Year’s Eve, 1955. Zeke Eblen, chief of detectives for the San Bernardino Sheriff’s Office, said the men stole expensive suits, sports jackets, and other clothing, which they took out a side door and loaded into a car.

Like Robert, William’s heroin addiction caused his troubles. In court on the burglary charges, he pleaded guilty and admitted to being an addict. Assistant County Probation Officer Merle Kay, said William was, “resigned to a life of institutional care without hope of rehabilitation or permanent treatment for his addiction.” All his previous attempts to get clean failed. He told Kay he would try to quit the habit if given probation, but confessed he had said the same thing a “thousand times” before.

In July 1967, police arrested William and his wife, Gloria, in Fort Worth, Texas, for forgery after a state computer detected a fake check they had tried to cash.

Working together, Robert, William, Robert’s wife Connie Sue, and an accomplice, George Pauldino, landed in U. S. District Court in Denver for passing stolen savings bonds in banks in Colorado Springs and Boulder.

According to U.S. Assistant Attorney Theodore Halaby, the group cashed some of the $200,000 worth of bonds they stole on December 12, 1971, from the safe of the Denver Public Administrator.

The brothers spent most of the 1970s either in court or prison.

The Schoengarth brothers paid a terrible price for making a dumb mistake as teenagers. Their addictions were a prison without walls. Reading between the lines, I realize they struggled to lead normal lives.

I’ve had many friends grapple with addiction. Several of them died of an O.D. Smart, funny, talented, each one had so much to give. I will never stop missing them.

Robert died in 1988, and William passed in 2005. The brothers may never have realized their potential, but I bet family and friends who saw the best in them mourn them still.

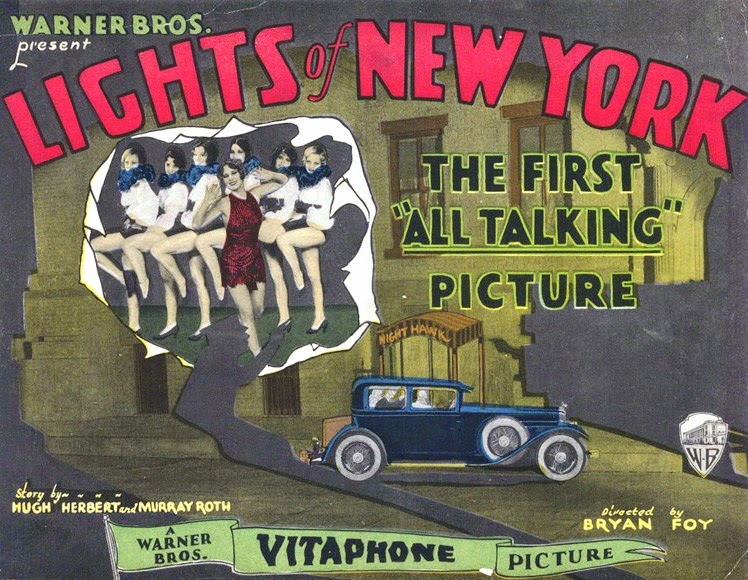

Welcome! The lobby of the Deranged L.A. Crimes theater is open. Grab a bucket of popcorn, some Milk Duds and a Coke and find a seat. Tonight’s feature is, THE LIGHTS OF NEW YORK (1928), starring Helene Costello, Wheeler Oakman, and Eugene Pallette.

This is the first feature film with all synchronous dialogue.

TCM says:

When bootleggers Jackson and Dickson, who have been hiding out in a small upstate New York town, learn that they finally can return to New York, they try to convince Eddie Morgan and his friend, a local barber named Gene, to come with them. With a promise from Jackson and Dickson that they will help the young men establish a barbershop in the city, Eddie asks his mother, who owns the town’s Morgan Hotel, to loan them $5,000 of her savings. Eddie and Gene set up the barbershop in New York but soon learn that it is merely a front for a speakeasy.

Enjoy the movie!

In March 1951, Ruth Gmeiner, a United Press Staff writer, published a story about the growing problem of teenage drug addiction. Officials described heroin use as a “contagious disease.” A federal grand jury in Detroit reported they had uncovered shocking conditions . . . “Young people ranging in age between 14 and 21 have become confirmed and inveterate users of heroin.” Every big city noticed an uptick in the number of juveniles arrested on drug charges.

In Los Angeles, Robert Schoengarth started using heroin in 1948 as a student at North Hollywood Junior High School. He and a group of his friends grew marijuana in the Hollywood Hills. They weren’t entrepreneurs, they were pot philanthropists. What they didn’t consume themselves, they gave away to friends.

Raise your hand if you made stupid choices at 14. Yeah. Me too. Fortunately, my choices didn’t have lifelong consequences.

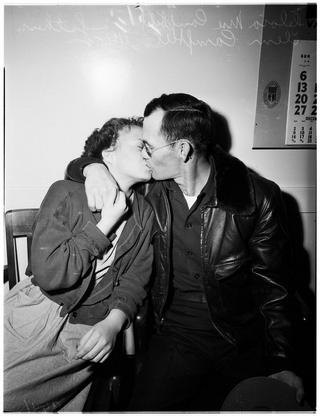

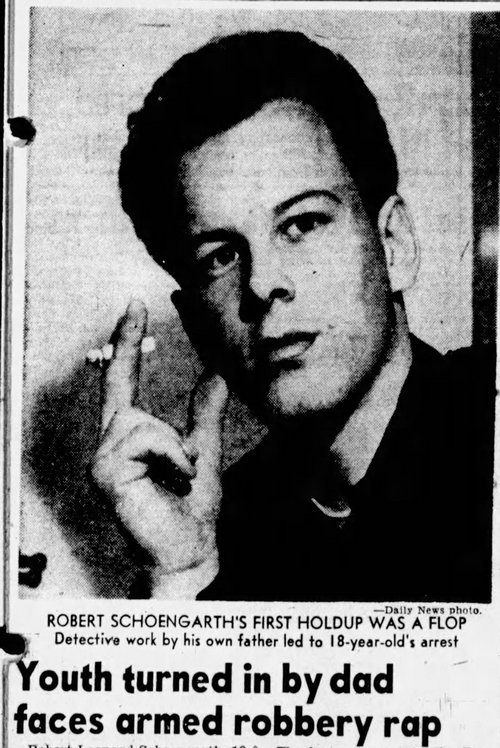

Late Wednesday evening, January 14, 1953, Morris Friedman worked behind the counter at his liquor store at 4100 Magnolia in Burbank. A dark-haired young man entered the store, bought a pack of cigarettes, and left. Moments later, he returned. He had a .22 in his pocket. He gestured at Friedman, “I want your money, sir.”

Friedman didn’t argue. He opened the cash register, grabbed a handful of bills, and handed them over. But the crook saw a few other bills in the drawer. He reached for them. Friedman grabbed the man’s arm, but the bandit pulled away and ran. The bandit was Robert.

Robert ran five blocks to his home. He replaced the gun, which belonged to his twin, William, in a dresser drawer. Passing through the living room where his father, Frank, spoke with a neighbor, he went into the front yard.

He called Frank from the house into the yard. “I told him I robbed the store.” It wasn’t Robert’s first brush with the law. Police arrested him twice before. Once for marijuana, and later for heroin. He spent time in the Los Angeles County Jail, and a California Youth Authority facility. He told his dad he’d been clean since his release. Frank didn’t believe him.

Robert said he couldn’t understand why he committed the robbery. He had a good job, making more than $62 a week as a mechanic’s apprentice. When Frank asked him for the stolen money, he gave it to him.

While Robert waited at home with his mother, Louise, for the police to arrive, Frank went to the liquor store and returned $33 to Friedman.

Patrolmen Ray Webb and Joe Mooney took Robert into custody. “I don’t know what’s wrong with me,” Robert said. “I suppose I have always been hanging around with the wrong crowd. That’s how I started using dope. Maybe they can put me in a hospital. Maybe it’d help me.”

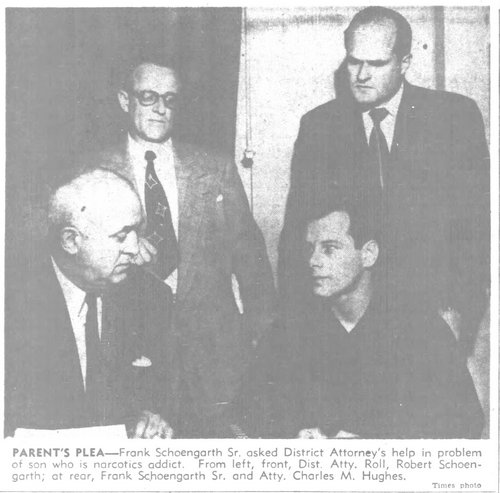

Robert’s pain is palpable. So is Frank’s. Frank explained his actions by saying he wanted to help Robert, and that he feared that Robert’s twin brother, William, an aircraft worker, might be wrongly accused.

In desperation, Frank reached out to the well-known newspaperwoman, Florabel Muir. He spoke to her about Robert. “He really isn’t a bad boy. He started getting into bad company when he was in junior high school. It was then he started smoking marijuana. I didn’t know about it until he was arrested.”

Robert’s incarcerations did him no good. Frank said, “He’s only got worse with each sentence. I asked him the other night what in the world had happened to him and where he got the idea of taking a gun and sticking up somebody for money. He looked at me, sneered, and answered, ‘In jail. What do you think?’”

Back home for only a month, Robert seemed to do well. Then he asked to borrow $10. Frank couldn’t figure out why Robert would be broke right after payday—unless he was using drugs again. Robert denied it.

Frank hoped they wouldn’t return Robert to jail. He wanted him to go to a hospital for treatment. That would be up to the court. District Attorney Ernest Roll ordered a full investigation of Robert’s story. Robert told him he would “like to kick the habit if I got the chance.” He told Roll about his “graduation” from marijuana to heroin. The D.A. learned how easy it was for Robert to get high in a California Youth Camp. A friend supplied heroin through the mail.

In judge Charles Fricke’s court, Robert pleaded guilty to one count of first-degree robbery. The judge said he would place Robert in one of the California Youth Authority institutions for another chance at sobriety.

In less than two years, Robert was out of CYA and back in the news.

Police arrested him and his brother William on dope charges in February 1955. With them was a 17-year-old girl. The twins had their own place at 11920 Riverside Drive in North Hollywood. Police found a hypodermic needle kit and two caps of heroin. The girl told officers she went with Robert downtown to Temple Street, where they scored a gram of heroin from a dealer for $15.

Maybe the evidence was insufficient for prosecution, because by October Robert was again under arrest for drugs.

Police booked Robert and 18-year-old Rosalyn Berman after stopping their car on Emelita Street and Lankershim Boulevard. Robert drove erratically, and police noticed Rosalyn drop a packet from the car. Both had fresh needle marks on their arms and appeared to be under the influence.

Only 20-years-old, and Robert’s life was circling the drain.

Even after six years of addiction and legal woes, Robert was young enough to change the course of his life. Could he do it?

NEXT TIME: Robert’s story continues.

Welcome! The lobby of the Deranged L.A. Crimes theater is open! Grab a bucket of popcorn, some Milk Duds and a Coke and find a seat. Today’s feature is CITY OF FEAR [1959], starring Vince Edwards, John Archer, Patricia Blair, and Steven Ritch.

Last week it was “Ice Skating Noir”, this time it is “Nuclear Noir” (not actual subgenres to my knowledge). In this film, Vince Edwards breaks out of San Quentin with a cannister he thinks contains heroin worth thousands. It doesn’t. It contains radioactive material. It reminds me of KISS ME DEADLY [1955].

Films in the 1950s, no matter what the genre, were obsessed with radioactivity. This one gets bonus points for great shots of Los Angeles in this film.

Enjoy the movie!