Have a wonderful Thanksgiving! I’m sure it will be better than Allen Ditson’s–unless you’re seated next to your least favorite relative at the dinner table.

The following is a repost from 2015.

PART 1

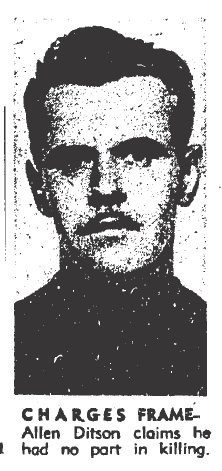

November 20,1962. Thanksgiving was two days away, but 41-year-old Allen Ditson wasn’t looking forward to it. He wouldn’t spend the day gnawing on a turkey drumstick or fighting with a cousin to claim the last slice of pumpkin pie. In fact Allen wouldn’t have the classic holiday dinner at all, unless he requested it for his last meal. If Governor Brown didn’t commute his death sentence, like he had done for Allen’s pal Carlos Cisneros, he would be executed in San Quentin’s gas chamber on Thanksgiving Eve.

* * *

In 1959 Allen owned a small jewelry and watch repair shop at 7715 Hollywood Way in the San Fernando Valley. The former Kansas farm boy was the father of two, a WWII veteran and former pilot who had spent five years in uniform before being honorably discharged. When he was mustered out of the service he took courses in watch and jewelry repair then opened his own business. He worked long hours and he continued to take classes related to his trade. The time he spent away from home was hard on his marriage; so hard in fact that he and his wife separated. Even though they no longer lived together he saw his children “at least twice a week” and contributed to their support. His mother-in-law said “he’s been good to all of us.”

In 1959 Allen owned a small jewelry and watch repair shop at 7715 Hollywood Way in the San Fernando Valley. The former Kansas farm boy was the father of two, a WWII veteran and former pilot who had spent five years in uniform before being honorably discharged. When he was mustered out of the service he took courses in watch and jewelry repair then opened his own business. He worked long hours and he continued to take classes related to his trade. The time he spent away from home was hard on his marriage; so hard in fact that he and his wife separated. Even though they no longer lived together he saw his children “at least twice a week” and contributed to their support. His mother-in-law said “he’s been good to all of us.”

On the surface Allen’s life appeared completely normal, but it wasn’t. The seemingly average businessman had a secret, he was the mastermind of a gang of violent armed robbers. Under his direction the gang of about 15 men had netted an estimated $150,000 (equivalent to approximately $1.2 in current dollars) between January and October of 1959.

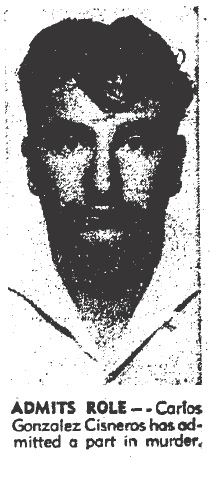

Like most gang leaders Allen had a lieutenant, his name was Carlos Gonzales Cisneros. According to court records Carlos lost his mother to tuberculosis and spent most of his infancy and childhood in foundling homes. He left school in 1950 when he was 17. He married, had four kids and worked at Lockheed as a sheet metal worker. He was 24-years-old and working the swing shift as a sheet metal worker at Lockheed when he met Allen. Allen was already running a gang and he slowly brought Carlos in. He began by telling the young man that “it would be nice to see him driving a Cadillac.” Eventually Carolos owned two Cadillacs.

Allen used skills he’d learned in the military to operate the gang. He was adamant that each member carry out his “assignment” with precision. If things went sideways and a gang member was busted he was to keep his mouth shut. Allen would see to it that he was provided with an attorney. Allen also made it clear that the penalty for being a “squealer” or a blackmailer was death.

During September and October 1959 a series of robberies were committed by Allen and Carlos and several gang members: Robert Ward, Keith Slaten, and Eugene and Norman Bridgeford.. During a robbery in October Robert “Bob” Ward failed his assignment. He was supposed to securely bind the store owners. He tied the man tightly, but the woman was able to free herself. Once freed the man grabbed his rifle and began shooting at the fleeing robbers. As they ran Eugene pitched the stolen cash box into some shrubs in an alley. Later that night Eugene and Carlos returned to retrieve the cash box and were busted on the spot. About a week later they made bail. During a meeting with Allen, Carlos and Eugene were informed that Bob was demanding money in exchange for keeping quiet about the gang.

On November 6, 1959, Allen told Eugene that he had “decided that tonight would be the best night to get rid of Bob Ward” because he was “through being blackmailed by a no-good-son-of-a-bitch like him.” Allen had already paid Bob $100 but had no intention of giving him one dime more. Allen came up with a plan to “…get rid of him.” Allen stayed at the store and let Carlos and Eugene implement his plan to take care of Bob.

Carlos and Eugene drove to a liquor store to pick up a couple of pints of booze. They knew that Bob was a heavy drinker and thought that he would be “more amiable” with a few shots of booze in him. Then they went to the house Bob shared with fellow gang member Keith Slaten. Carlos parked the Cadillac on the street in front of the house. Keith had seen them pull up and went out to greet them. Keith and Bob thought they were going to pull another robbery. The men piled into Keith’s Ford. Keith was behind the wheel, Bob was in the passenger seat, and Eugene and Carlos sat in the back. They spent about 45 minutes drinking. Carlos picked up a hammer from the floor of Keith’s car and brought it down on the back of Bob’s head. Bob fell against Keith and screamed: “Keith, help me. They are trying to kill me.” Keith had his own life to worry about and gave Bob a shove so he’d be an easier target for Carlos–then he ran into the house. Carlos called him back and said, “just take it easy and it’ll be all right.”

In the interim Bob had managed to get out of the car and was leaning against a tree when Carlos found him and beat him down to the ground. Carlos backed his car into the driveway and after delivering a few more blows to Bob’s head put him in the trunk of the car. Carlos and Eugene drove off and Keith followed them in the Ford. Carlos had driven about half a mile before Bob regained consciousness and started pleading from his confinement in the trunk to be released. He said he thought his eye had come out of its socket. Carlos told him to be quiet and then turned up the car radio so he wouldn’t be able to hear Bob call his name.

Now thoroughly rattled Carlos misjudged a turn, struck the curb with the front wheel of the car and blew a tire. He spotted a pay phone, gave Eugene some change and told him to call Allen and ask him to bring a spare tire and a heavy duty jack (after all it was a Cadillac with a man in the trunk). About an hour later Allen arrived with a friend of his, Leonard York. They changed the tire and then Carlos, with Bob still in the trunk, took off for the jewelry store. Eugene and Leonard rode with Allen back to the store. When they arrived they could hear unintelligible noises coming from the trunk of the Cadillac. Allen said they’d have to get rid of Bob before the neighbors heard him and called the cops. Eugene took Leonard home and then begged off the rest of the evening saying he was sick.

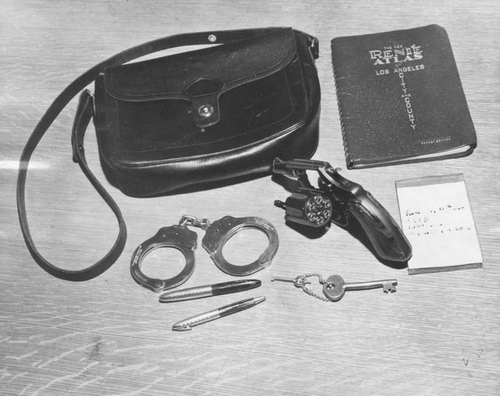

Allen took a .38 revolver from the store and he and Carlos drove Bob out to the Newhall Pass. Allen opened the trunk and ordered Bob to get out. Unaided, the seriously injured man got out and stood on his feet. He asked for a cigarette. Allen shot him in the chest. He fell, got up, and ran toward Carlos. As they rolled over an embankment Allen shot Bob in the back paralyzing him. Allen walked down the incline to see if Bob was finally dead. He wasn’t. He said, “Give me another one.” Allen knelt down beside him, pressed the .38 to his head and killed him.

PART 2

After shooting Bob Ward to death with a .38, Allen Ditson had to figure out what to do with the body. At least Carlos Cisneros was there to help him. Carlos began to dig a grave with his bare hands until Allen brought him a butcher knife from the car. Once the grave was ready Allen said that they would have to dismember Bob to prevent identification if someone should discover his remains. Using the butcher knife they removed Bob’s head and each arm at the elbow. They buried the remains and then tossed the head and arms into the truck of the car and drove back Allen’s store.

While Allen and Carlos were coping with the dead body, Keith Slaten turned up at the house of his friend Martha Hughes. He told her that he’d been in a fight and wanted to clean up his car. He was covered with blood and shaking like a leaf and Martha told him she didn’t believe he’d been in a fight. He blurted out: “Well, God damn. All right, so we killed him.” Allen couldn’t keep his mouth shut either. The day after Bob’s murder he told Eugene Bridgeford everything that had happened after he pleaded illness and left.

What happened to Bob’s head and arms? Allen and Carlos took them to the home of Christine Longbrake a few days after the murder. Christine was an acquaintance of Allen’s and a couple of weeks before the crime she’d been in Allen’s shop and he’d told her that “there was someone they had to get rid of” because the man was trying to blackmail him. Allen asked to use her garage as a place to get rid of the guy but she thought he was kidding. When Allen and Carlos turned up with two boxes Christine knew she couldn’t refuse any request they made. She stayed upstairs while the boxes were taken to the cellar. Allen knocked Bob’s teeth out with a hammer then placed what was left of him in the hole and then poured in a bottle of acid. When the men came back upstairs Christine smiled nervously and said: “Is it somebody I know?” They smiled back and Allen said that she wouldn’t know him. Then he and Carlos drove out to Hansen Dam and tossed Bob’s teeth and dental plate into a gravel pit.

Christine hadn’t seen the last of Allen and Carlos. Not more than a few days after they’d buried the boxes in her cellar Carlos stopped by and told her everything. He even told her what was in the boxes underneath her house. Her nerves weren’t soothed when he told her that he could never kill a woman. In fact she was so unnerved that she told Allen she was going to move “…because I couldn’t stand living in this house …” Allen told her that if it bothered her so much he’d pay her rent if she’d just hang on a bit longer.

A bit longer turned out to be several months. In June 1960 Allen asked George Longbrake, Christine’s brother-in-law, if he would dig up the two arms and head under the house. George agreed and Allen bought him some aluminum foil so he could wrap up the bits of Bob that remained. Then, since it seemed the entire Longbrake family was involved anyway, Allen asked Wynston Longbrake, Christine’s husband, if he’d “help bury something.” Allen, Carlos, and Wynston drove from L.A. on Highway 99 to a place about 14 miles from Castaic Junction. He turned off the highway for about 100 yards. Carlos waited in the car while the other two carried the macabre foil wrapped packages out of sight, then dug a post-hole and buried them.

Because Allen and Carlos were incapable of keeping quiet about what they’d done it was only a matter of time before the law caught up with them. The remaining gang members began to fear Allen more than they did the cops. On June 17, 1960 Keith Slaten went to the police and a few days later Eugene Bridgeford did the same. The statements were enough for the police to get a warrant to examine Carlos’ Cadillac–they found traces of human blood in the trunk. One day later the police conducted a similar examination of Keith’s Ford and found human blood on the upholstery. On June 28, “sometime after 1:00 p.m.” Allen and Carlos were taken into custody.

Because Allen and Carlos were incapable of keeping quiet about what they’d done it was only a matter of time before the law caught up with them. The remaining gang members began to fear Allen more than they did the cops. On June 17, 1960 Keith Slaten went to the police and a few days later Eugene Bridgeford did the same. The statements were enough for the police to get a warrant to examine Carlos’ Cadillac–they found traces of human blood in the trunk. One day later the police conducted a similar examination of Keith’s Ford and found human blood on the upholstery. On June 28, “sometime after 1:00 p.m.” Allen and Carlos were taken into custody.

Allen maintained his innocence, but Carlos appeared to be genuinely remorseful and he wanted to talk. In his 1959 book, The Compulsion to Confess, Theodore Reik said “There is … an impulse growing more and more intense suddenly to cry out his secret in the street before all people, or in milder cases, to confide it at least to one person, to free himself from the terrible burden. The work of confession is thus that emotional process in which the social and psychological significance of the crime becomes preconscious and in which all powers that resist the compulsion to confess are conquered.”

Allen’s protestations of innocence didn’t sway the jury of five men and seven women. He was found guilty and sentenced to death. Carlos was also found guilty in Bob’s murder and sentenced to death. In early November 1962, with their executions imminent, Governor Brown presided over a clemency hearing. Carlos’ remorse saved him. His sentence was commuted to life.

Allen never admitted his guilt to the police, but he did confess to nearly everyone else he knew. On November 21, 1962, without requesting a special holiday meal, Allen kept his Thanksgiving Eve date with the gas chamber.

As the phone called neared an end, Thomas said, “Well, I better go now because I’m going to see what’s happening. . . I don’t want Paul to hurt Ramon.”

As the phone called neared an end, Thomas said, “Well, I better go now because I’m going to see what’s happening. . . I don’t want Paul to hurt Ramon.”

By now may be wondering what Marion’s criminal behavior in Ohio, Nebraska, and Colorado has got to do with Los Angeles. Simple. Like many others before him, following his release from prison the ex-con moved to Los Angeles–land of bright blue skies, sunny beaches and, in Marion’s case, third chances. Prison may have mellowed him, and perhaps it did–for a while. From 1940 to 1957 if he committed any crimes they weren’t serious enough to get his name into the newspapers. Unfortunately, Marion proved to be incapable of keeping his life on track.

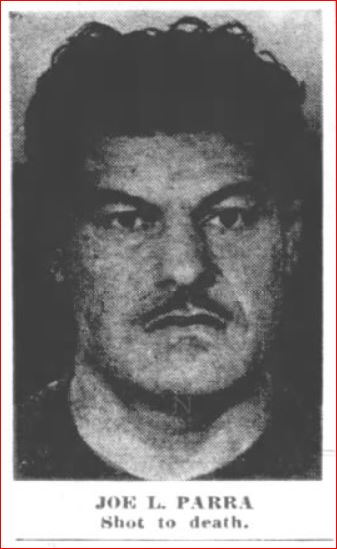

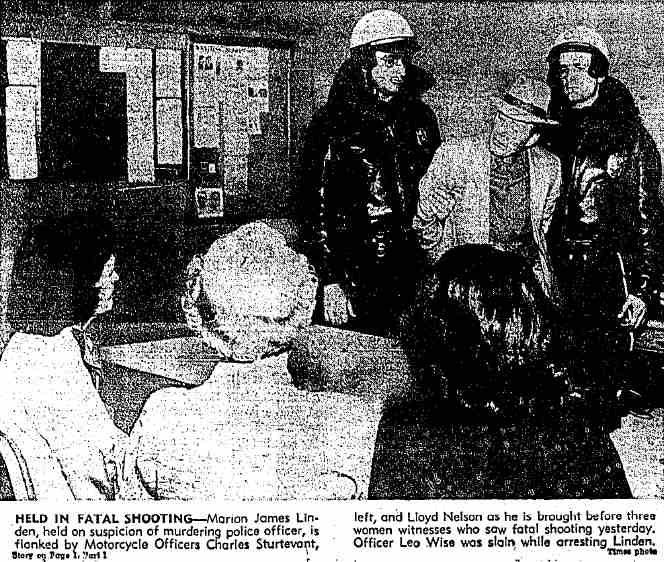

By now may be wondering what Marion’s criminal behavior in Ohio, Nebraska, and Colorado has got to do with Los Angeles. Simple. Like many others before him, following his release from prison the ex-con moved to Los Angeles–land of bright blue skies, sunny beaches and, in Marion’s case, third chances. Prison may have mellowed him, and perhaps it did–for a while. From 1940 to 1957 if he committed any crimes they weren’t serious enough to get his name into the newspapers. Unfortunately, Marion proved to be incapable of keeping his life on track. Lieutenant Gebhart took the suspect to Homicide Division. As they drove, the suspect said: “I hope you have me for murder. I shot that #@$%&*cop and I intended to kill him. If I had an opportunity I would kill all of you. … I tried to shoot him in the heart. … I shot him with a .32 and I didn’t think it would do that much damage, but I hoped it would.”

Lieutenant Gebhart took the suspect to Homicide Division. As they drove, the suspect said: “I hope you have me for murder. I shot that #@$%&*cop and I intended to kill him. If I had an opportunity I would kill all of you. … I tried to shoot him in the heart. … I shot him with a .32 and I didn’t think it would do that much damage, but I hoped it would.”

In 1959 Allen owned a small jewelry and watch repair shop at 7715 Hollywood Way in the San Fernando Valley. The former Kansas farm boy was the father of two, a WWII veteran and former pilot who had spent five years in uniform before being honorably discharged. When he was mustered out of the service he took courses in watch and jewelry repair then opened his own business. He worked long hours and he continued to take classes related to his trade. The time he spent away from home was hard on his marriage; so hard in fact that he and his wife separated. Even though they no longer lived together he saw his children “at least twice a week” and contributed to their support. His mother-in-law said “he’s been good to all of us.”

In 1959 Allen owned a small jewelry and watch repair shop at 7715 Hollywood Way in the San Fernando Valley. The former Kansas farm boy was the father of two, a WWII veteran and former pilot who had spent five years in uniform before being honorably discharged. When he was mustered out of the service he took courses in watch and jewelry repair then opened his own business. He worked long hours and he continued to take classes related to his trade. The time he spent away from home was hard on his marriage; so hard in fact that he and his wife separated. Even though they no longer lived together he saw his children “at least twice a week” and contributed to their support. His mother-in-law said “he’s been good to all of us.”

Because Allen and Carlos were incapable of keeping quiet about what they’d done it was only a matter of time before the law caught up with them. The remaining gang members began to fear Allen more than they did the cops. On June 17, 1960 Keith Slaten went to the police and a few days later Eugene Bridgeford did the same. The statements were enough for the police to get a warrant to examine Carlos’ Cadillac–they found traces of human blood in the trunk. One day later the police conducted a similar examination of Keith’s Ford and found human blood on the upholstery. On June 28, “sometime after 1:00 p.m.” Allen and Carlos were taken into custody.

Because Allen and Carlos were incapable of keeping quiet about what they’d done it was only a matter of time before the law caught up with them. The remaining gang members began to fear Allen more than they did the cops. On June 17, 1960 Keith Slaten went to the police and a few days later Eugene Bridgeford did the same. The statements were enough for the police to get a warrant to examine Carlos’ Cadillac–they found traces of human blood in the trunk. One day later the police conducted a similar examination of Keith’s Ford and found human blood on the upholstery. On June 28, “sometime after 1:00 p.m.” Allen and Carlos were taken into custody.