The Supreme Court is trampling women’s rights and there is no reason to believe it will stop. Can we expect to be deprived of voting rights? Will they force us to perform only those jobs deemed suitable for women? I, for one, believe this court has no lower bound. I await an apocalypse.

While I await said apocalypse, I divert my energy into research. It is my escape and my happy place. Anyway, during a recent search of old newspapers, I found several intriguing cases from 1921.

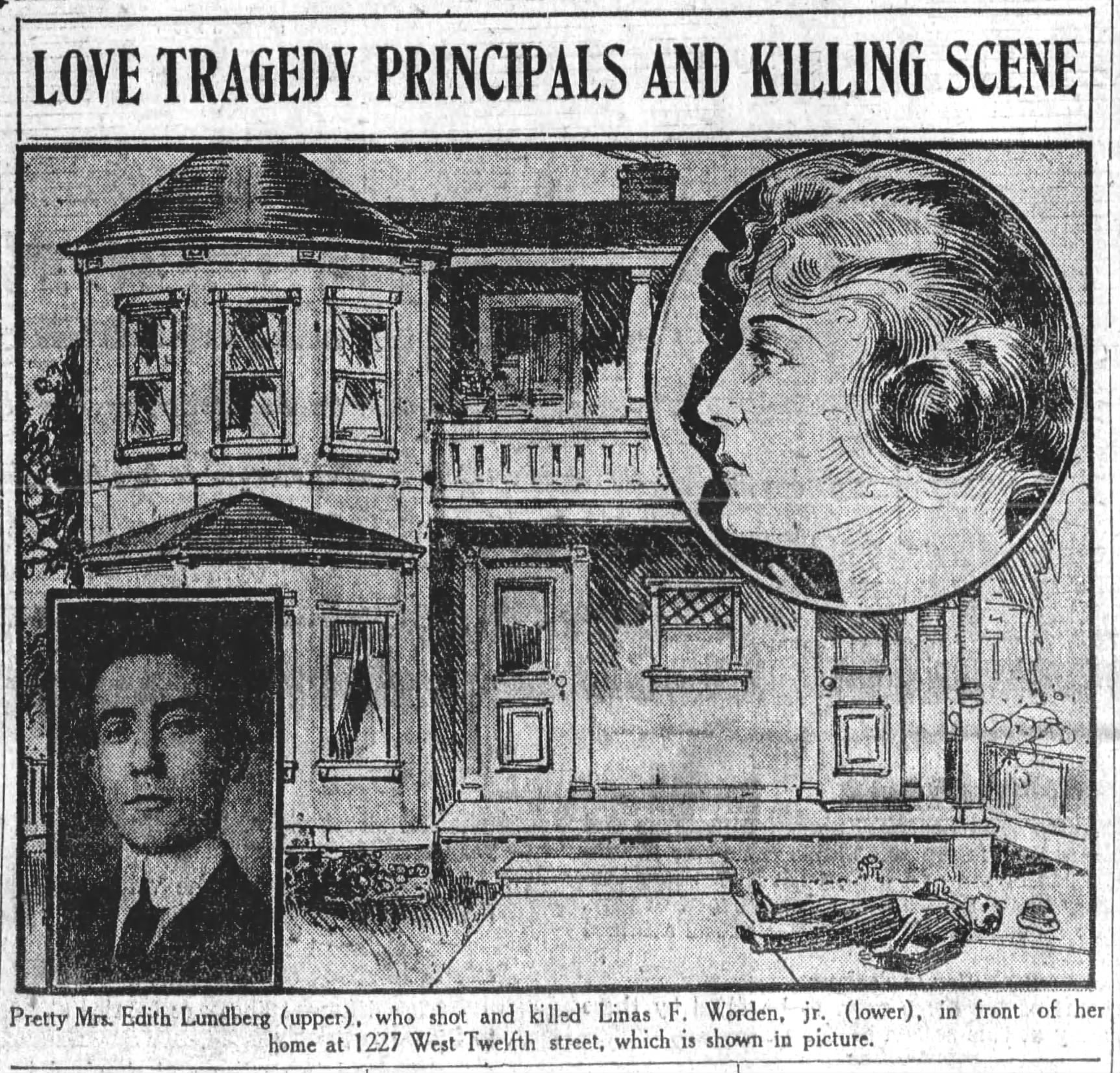

I’ll begin with Edith Lundberg.

The Los Angeles newspaper headlines for 1921, reflect nothing short of a female crime wave. On any given day, Edith Lundberg shares column space with Louise Peete (unmasked years later as a serial killer); Erie Mullicane, a young woman accused of killing her baby, and numerous other women facing the criminal justice system for a variety of crimes.

Born to Anna Marie Hart and William Allen Vosburgh (Vosberg) on June 29, 1891 in Illinois, Edith Mae Vosberg had an older brother, Gayne born in 1890, and a sister, Ethel, born 1895

Married, at 18 years-old, to Arthur Lundberg and widowed seven years later in 1916, Edith Lundberg’s life was not very different from other women her age. Many young women lost children, and husbands, before their 30th birthday. Luckier than some, Edith moved from Missouri to Santa Barbara, California, to live with her younger sister, Ethel. Ethel married Harvey Clark, a successful movie character actor. They welcomed Edith.

Situated a short distance from the beach, the Clark’s house at 322 West Mission Street must have made a pleasant change for Edith from the harsh mid-western winters, and the loneliness of widowhood. Even with its desirable location, it was a long commute to get to the movie studios, so sometime during 1920, the Clarks moved to Los Angeles, and Edith accompanied them. She moved in with her parents, who also fled the harsh midwestern weather. She found a job as a stenographer in the mechanical department of the Hall of Records.

In September 1920, she started dating Linus Worden, Jr., a local car salesman. Linus served in the motor transport corps during the war, earning his sergeant’s stripes. A post-war segue to working in auto sales seemed perfect for him.

Prior to meeting Linus, Edith resumed use of her maiden name. Linus and his family knew her as Miss Vosberg. She did not mention her widowed status. After five years alone, she may have preferred to put her sadness behind her and start fresh. Linus called on at least once a week. Edith’s mother believed the relationship was on a track to marriage, but the Wordens had a different take on it. They believed it was casual companionship. Both families agreed the pair enjoyed each other’s company.

On February 8, 1921, the couple went out for a drive. A couple of hours later, Linus’ car pulled up at the curb in front of the Vosberg home at 1227 West Twelfth Street. (The house is long gone.) In the house, her parents, and her sister and her brother-in-law, heard laughter and conversation from the car. After a momentary silence, four gunshots cracked. A agonized cry followed. Linus got out of the car, took a few steps toward the house and collapsed on the sidewalk.

F.E. Andreani, a near neighbor, heard the commotion and ran over to Linus to render aid. Linus said, “I’m shot.” Then stopped trying to speak. Andreani pulled the fallen man into his car and rushed him to the nearest receiving hospital, but Linus died before they could reach medical help. One bullet pierced his heart, and another lodged in his stomach.

Linus’ wounds accounted for two shots. What about the other two? After shooting Linus, Edith held the pistol against her abdomen and shot twice. She made it to her parents’ porch before falling. At the hospital, Edith begged to die. She told the attending surgeons, “I couldn’t live with him and I couldn’t live without him. I made up my mind to kill him and I shot him.” She also muttered she and Linus “felt blue.” She said she planned to kill him and then herself.

As they waited for word on Edith’s condition, police began their investigation. They learned Edith purchased the gun at a pawnshop two weeks earlier. She used an assumed name.

Two days after the crime, Edith lay near death in the county hospital. Her motive remained unclear. One doctor, Edward H. Morrissey, president of the Los Angeles Association of Optometrists, theorized, “If this young woman quarreled with Worden, she undoubtedly did so because of the low ebb of her vitality caused her to be irritable. Any undue excitement which might have come while she was in this condition could have caused her to lose control of herself. The majority of criminals in our jails and inmates of our county farms are victims of defective vision.” An interesting theory, for sure. Dr. Morrissey based it on a report that Edith complained of a severe headache and problems with her eyesight the day of Linus’ murder.

Police had their own theory, which did not involve faulty eyesight. They believed Edith premeditated the murder because she purchased the revolver in advance. Another odd thing, Edith wrote, but did not mail, a letter to a friend in which she stated: “I have a strange feeling. If anything happens, I will come to you if I am allowed.”

Edith’s condition tread a thin line between life and death for days before doctors felt confident enough to declare her on the road to recovery. The news is enough for the District Attorney to file a murder charge against Edith. They move her from the county hospital to a bed in the county jail.

According to her attorney, T.E. Justice, (perfect name for an attorney, right?) Edith would plead insanity. Edith said, “I don’t know why I killed him. I loved him and he loved me, but we were both moody, subject to despondency and melancholy, and I did not feel that we would be happy married. I had planned for some time to take my own life, but had no intention of taking his. But I expect to pay the penalty, and now my chief worry is for his mother, for he was everything to her.”

Her difficult recovery postponed her preliminary hearing until April 5. Los Angeles Police Department Detective Sergeant Bean remained baffled by Edith’s conflicting statements. On one hand, she claimed she couldn’t live with Linus; other the other hand she could not live without him. In the next breath, she asserted the shooting was a terrible accident. She intended to kill herself, not to harm Linus. Maybe the trial would clarify her true motive.

On April 5, her attorney (soon to be replaced by a public defender) previewed Edith’s defense—chronic melancholia.

NEXT TIME: Edith on trial.