Ewing’s attorneys told reporters they were worried that their client had met with “foul play”. Both the police and the district attorney were convinced that Ewing’s convenient disappearance was a hoax.

Ewing’s attorneys told reporters they were worried that their client had met with “foul play”. Both the police and the district attorney were convinced that Ewing’s convenient disappearance was a hoax.

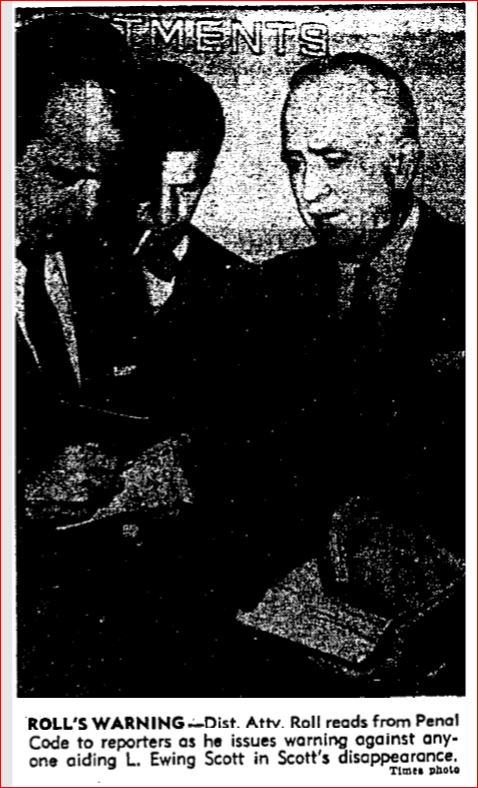

District Attorney Ernest Roll said: “By this disappearing act he (Ewing) has apparently again avoided taking the stand and testifying under oath in one of our civil courts. It is further interesting to note that no missing person report has been filed with the Los Angeles Police Department in connection with Scott’s alleged disappearance.” Roll added that if Ewing didn’t appear for his next scheduled court appearance then, “proper legal steps will be taken to produce him.”

With $179,000 (equivalent to $1.5M today) of his missing wife’s assets unaccounted for, and likely in his possession, Ewing could buy a ticket to anywhere in the world. In his case it would likely be a place with no extradition treaty with the U.S.

If his disappearance was voluntary, then he was in contempt of court in connection with the $6,000 judgement against him by the Wolfer Printing Company for the costs they incurred publishing his book, “How to Fascinate Men.”

Ewing’s recent companion, Marianne Beaman, might have been worried about Ewing after the sedan he’d been driving had been discovered in Santa Monica with bullet holes through the windshield. But her worry paled in comparison to that of Louis and Irving Glasser. The Glassers were the bail bondsmen who had guaranteed Ewing’s bail. If Ewing was a no-show, they’d be out the money.

So, was Ewing sitting on a distant beach sipping a cocktail with a colorful little umbrella in it; or was he dead and buried in an unmarked shallow grave along Angelus Crest Highway? Nobody knew for sure.

So, was Ewing sitting on a distant beach sipping a cocktail with a colorful little umbrella in it; or was he dead and buried in an unmarked shallow grave along Angelus Crest Highway? Nobody knew for sure.

As in in many missing persons cases there were reported sightings of Ewing everywhere from Long Beach to Mexico. None of the sightings were verified.

On May 15, 1956, after Ewing failed to show up for his court appearance, District Attorney Roll requested bail in the amount of $100,000, but Superior Court Judge Herbert V. Walker had a better idea. He ordered Ewing’s original $25,000 bail forfeited and issued a bench warrant for his arrest.

District Attorney Roll read California Penal Code Section 32 aloud in the courtroom. He intended to drive home his point that anyone who “harbors, conceals or aids a principal … with the intent that said principal may avoid or escape from arrest, trial, conviction or punishment…” would be in an enormous amount of trouble with the law.

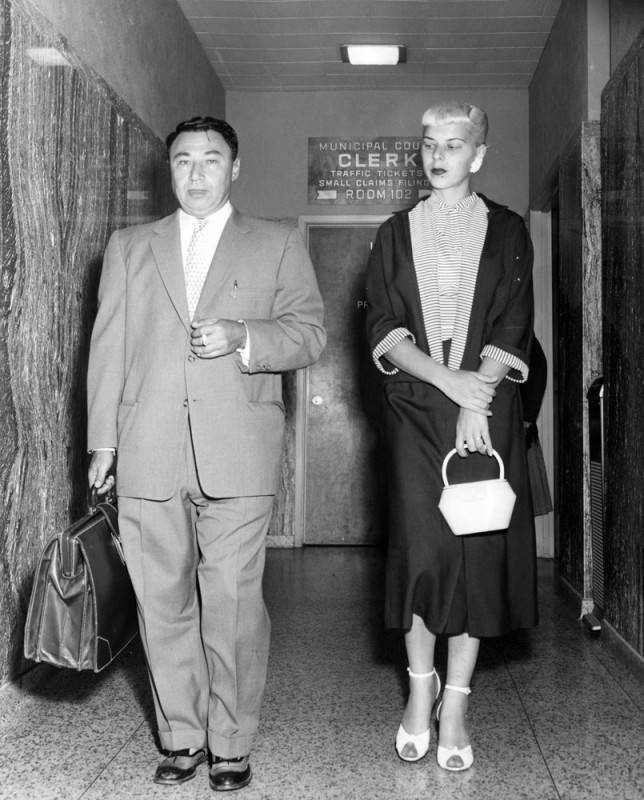

If Ewing was missing under his own steam, a likely accessory would be Marianne Beaman, and the police and the district attorney intended to hold her feet to the fire. They had a list of questions that she would be required to answer if she wanted to remain a free woman. One of the questions had to do with a few gifts given to her by Ewing. Items of clothing that had belonged to Evelyn.

A credible sighting of Ewing came from Bishop, California where he had allegedly spent the nights of May 2, 3, 4 and 5. Chief of Detectives Gordon Bowers of the Sheriff’s Department said he had alerted law enforcement entities from Los Angeles north to the Canadian border.

Ewing remained at large through the rest of 1956. On April 15, 1957, eleven months after Ewing had vanished, a man who gave his name as Lewis E. Stewart was arrested in Windsor, Ontario, Canada just across the Detroit River from Detroit. Mr. Stewart strongly resembled Ewing Scott. And what a coincidence — his initials were the same.

Lewis Stewart was quickly confirmed to be the fugitive Ewing Scott and was confined to a cell on the fifth floor of the Wayne County Jail. As always, Ewing was impeccably dressed and vocal on the topic of his innocence in the death of his wife. “I’m the goat,” he said. “They are trying to make me take the rap for somebody else. I am innocent. I am being prejudged. I do not want to go back to California.”

Ewing was charming and friendly during his interview until a reporter asked him point-blank if he had murdered his wife. Scott replied, “That is an asinine question. It is just plain ridiculous and stupid. It is the last thing I would want to do.”

Ewing was charming and friendly during his interview until a reporter asked him point-blank if he had murdered his wife. Scott replied, “That is an asinine question. It is just plain ridiculous and stupid. It is the last thing I would want to do.”

Ewing unsuccessfully fought extradition to California, and by mid-May he was returned to Los Angeles.

Ewing’s attorney filed a plea to dismiss the murder charge against him, but the judge wasn’t having it. Ewing’s trial for the murder of his wife was set for mid-September.

As Ewing awaited trial he spent a lot of his time attempting to sell his story to the movies. He wanted $200,000 for the tale and he claimed he planned to spend a significant portion of the sum to “follow up on a number of hot leads on the whereabouts of Mrs. Scott.” According to Ewing Evelyn was missing, not dead.

As far as any possible film, the charming, sophisticated and good looking English actor, Ronald Colman, seemed to Ewing to be the obvious choice to portray him on the big screen. Who would play Evelyn? Ewing wasn’t so sure. “As far as Mrs. Scott goes, I don’t know who would be exactly right. perhaps an older Peggy Lee, or Mary Astor. I’d have to see the woman first.” After further thought, Ewing said about the as yet unnamed actress, “I do know that she’ll have to be smart, dignified and rather good looking–and definitely not the wisecracking type.” Okay. I guess Joan Blondell wouldn’t be considered — although personally I think she would have been a fantastic choice.

As far as any possible film, the charming, sophisticated and good looking English actor, Ronald Colman, seemed to Ewing to be the obvious choice to portray him on the big screen. Who would play Evelyn? Ewing wasn’t so sure. “As far as Mrs. Scott goes, I don’t know who would be exactly right. perhaps an older Peggy Lee, or Mary Astor. I’d have to see the woman first.” After further thought, Ewing said about the as yet unnamed actress, “I do know that she’ll have to be smart, dignified and rather good looking–and definitely not the wisecracking type.” Okay. I guess Joan Blondell wouldn’t be considered — although personally I think she would have been a fantastic choice.

Ever the optimist, Ewing said he had no desire to portray himself in the film. He was, of course, certain that he would be free to accept the role if offered and not pacing the yard at San Quentin, or awaiting execution on death row instead of sitting in a canvas director’s chair with his name emblazoned on the back.

The district attorney’s decision to prosecute Ewing for Evelyn’s murder when her body had not been found was an enormous risk. Ewing was the first person in California to face such a trial, making his case one for the books.

Despite the lack of a physical body, Deputy District Attorney J. Miller Leavy, was confident that the corpus delicti of murder could be established. There was a mountain of compelling circumstantial evidence to bolster the State’s case. Leavy was not only certain of a conviction, he asked for the death penalty.

Despite the lack of a physical body, Deputy District Attorney J. Miller Leavy, was confident that the corpus delicti of murder could be established. There was a mountain of compelling circumstantial evidence to bolster the State’s case. Leavy was not only certain of a conviction, he asked for the death penalty.

One of the highlights of Ewing’s trial was a visit, by the jurors, to the Beverly Hills home he and Evelyn had occupied. Of particular interest to the jurors was the backyard incinerator where the remains of women’s clothing were found, and also the spot where Evelyn’s denture and eyeglasses had been discovered. One of the female jurors opened the door to the incinerator and peered in — although what she expected to find wasn’t clear.

The defense attempted to cast doubt on the murder charge by claiming Evelyn had been spotted living on the East Coast, but they fell far short of refuting the prosecution’s robust case.

On December 21, 1957, the jury in the Ewing Scott murder trial returned a verdict of guilty of murder in the first degree for the slaying of Evelyn Scott. Ewing showed no emotion as the verdict was read.

Several days later, following four hours of deliberation, the jury returned with their sentence: life in prison.

Several days later, following four hours of deliberation, the jury returned with their sentence: life in prison.

The jurors who agreed to speak with reporters said that they had tried to find a way to acquit Ewing but “we just couldn’t.” The evidence of Ewing’s greed, manipulation, and the physical evidence of Evelyn’s glasses and denture, and the ashes of clothing, were too great to overcome. Nobody bought his contention that Evelyn was a drunk who left home of her own volition.

Ewing appealed his conviction. The appeal was denied. He also had the balls to petition for $600 per month so that, according to him, he could pay to mount an investigation into Evelyn’s disappearance. In February 1963, Ewing was legally denied his request to share in Evelyn’s estate.

In 1974, seventeen years after his conviction for Evelyn’s murder, Ewing was granted parole. He refused to leave prison. His reason for refusal was that he felt accepting parole would be tantamount to accepting guilt for Evelyn’s murder.

Still vociferously denying his guilt, Ewing was released from prison in 1978.

NEXT TIME: Corpus Delicti Epilogue

Ewing Scott was released from prison in 1974, still vehemently denying that he had murdered his wife Evelyn in 1955.

Ewing Scott was released from prison in 1974, still vehemently denying that he had murdered his wife Evelyn in 1955.

On August 17, 1987, ninety-one year-old Ewing Scott died at the

On August 17, 1987, ninety-one year-old Ewing Scott died at the

Ewing’s attorneys told reporters they were worried that their client had met with “foul play”. Both the police and the district attorney were convinced that Ewing’s convenient disappearance was a hoax.

Ewing’s attorneys told reporters they were worried that their client had met with “foul play”. Both the police and the district attorney were convinced that Ewing’s convenient disappearance was a hoax. So, was Ewing sitting on a distant beach sipping a cocktail with a colorful little umbrella in it; or was he dead and buried in an unmarked shallow grave along Angelus Crest Highway? Nobody knew for sure.

So, was Ewing sitting on a distant beach sipping a cocktail with a colorful little umbrella in it; or was he dead and buried in an unmarked shallow grave along Angelus Crest Highway? Nobody knew for sure.

Ewing was charming and friendly during his interview until a reporter asked him point-blank if he had murdered his wife. Scott replied, “That is an asinine question. It is just plain ridiculous and stupid. It is the last thing I would want to do.”

Ewing was charming and friendly during his interview until a reporter asked him point-blank if he had murdered his wife. Scott replied, “That is an asinine question. It is just plain ridiculous and stupid. It is the last thing I would want to do.” As far as any possible film, the charming, sophisticated and good looking English actor, Ronald Colman, seemed to Ewing to be the obvious choice to portray him on the big screen. Who would play Evelyn? Ewing wasn’t so sure. “As far as Mrs. Scott goes, I don’t know who would be exactly right. perhaps an older Peggy Lee, or Mary Astor. I’d have to see the woman first.” After further thought, Ewing said about the as yet unnamed actress, “I do know that she’ll have to be smart, dignified and rather good looking–and definitely not the wisecracking type.” Okay. I guess Joan Blondell wouldn’t be considered — although personally I think she would have been a fantastic choice.

As far as any possible film, the charming, sophisticated and good looking English actor, Ronald Colman, seemed to Ewing to be the obvious choice to portray him on the big screen. Who would play Evelyn? Ewing wasn’t so sure. “As far as Mrs. Scott goes, I don’t know who would be exactly right. perhaps an older Peggy Lee, or Mary Astor. I’d have to see the woman first.” After further thought, Ewing said about the as yet unnamed actress, “I do know that she’ll have to be smart, dignified and rather good looking–and definitely not the wisecracking type.” Okay. I guess Joan Blondell wouldn’t be considered — although personally I think she would have been a fantastic choice. Despite the lack of a physical body, Deputy District Attorney J. Miller Leavy, was confident that the corpus delicti of murder could be established. There was a mountain of compelling circumstantial evidence to bolster the State’s case. Leavy was not only certain of a conviction, he asked for the death penalty.

Despite the lack of a physical body, Deputy District Attorney J. Miller Leavy, was confident that the corpus delicti of murder could be established. There was a mountain of compelling circumstantial evidence to bolster the State’s case. Leavy was not only certain of a conviction, he asked for the death penalty. Several days later, following four hours of deliberation, the jury returned with their sentence: life in prison.

Several days later, following four hours of deliberation, the jury returned with their sentence: life in prison. Evelyn’s brother, Raymond, was satisfied with the outcome of the trustee battle — the bank was his nominee. Ewing’s attorneys were said to be plotting a new strategy to put him back in charge of the estimated $270,000 estate. But losing the trustee fight wasn’t Ewing’s most pressing problem. Rumors of a grand jury and possible indictments were looming large on the horizon.

Evelyn’s brother, Raymond, was satisfied with the outcome of the trustee battle — the bank was his nominee. Ewing’s attorneys were said to be plotting a new strategy to put him back in charge of the estimated $270,000 estate. But losing the trustee fight wasn’t Ewing’s most pressing problem. Rumors of a grand jury and possible indictments were looming large on the horizon. The grand jury indicted Ewing on 13 counts, 4 of theft and 9 of forgery. His constant companion was divorcee Marianne Beaman who seemed to have no problem consorting with a man who may have murdered his wife. Marianne even flatly refused to testify about out-of-town jaunts she and Ewing had taken. Her refusal to speak could lead to a contempt charge.

The grand jury indicted Ewing on 13 counts, 4 of theft and 9 of forgery. His constant companion was divorcee Marianne Beaman who seemed to have no problem consorting with a man who may have murdered his wife. Marianne even flatly refused to testify about out-of-town jaunts she and Ewing had taken. Her refusal to speak could lead to a contempt charge.

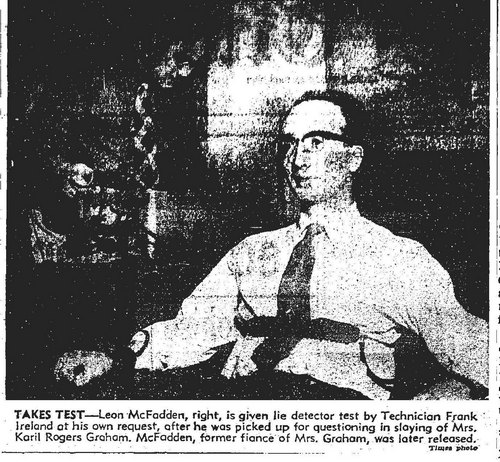

Donald Bashor, 27, confessed to dozens of local burglaries and to the bludgeon slayings of Karil Graham and Laura Lindsay. Under intense police questioning Donald didn’t admit to any further offenses, and as far as investigators could tell he’d revealed the extent of his crimes.

Donald Bashor, 27, confessed to dozens of local burglaries and to the bludgeon slayings of Karil Graham and Laura Lindsay. Under intense police questioning Donald didn’t admit to any further offenses, and as far as investigators could tell he’d revealed the extent of his crimes.

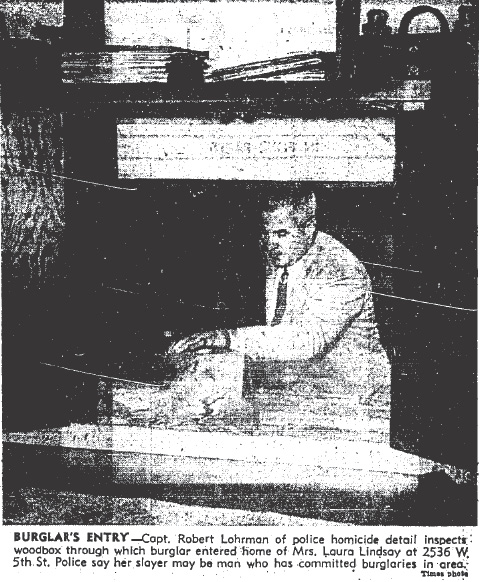

On May 25, 1956 the Los Angeles Times reported that there had been another murder the night before. The circumstances were very similar to Karil Graham’s slaying and it was in the same general neighborhood. The victim was Laura Lindsay, a 62-year-old legal secretary. Her home at

On May 25, 1956 the Los Angeles Times reported that there had been another murder the night before. The circumstances were very similar to Karil Graham’s slaying and it was in the same general neighborhood. The victim was Laura Lindsay, a 62-year-old legal secretary. Her home at

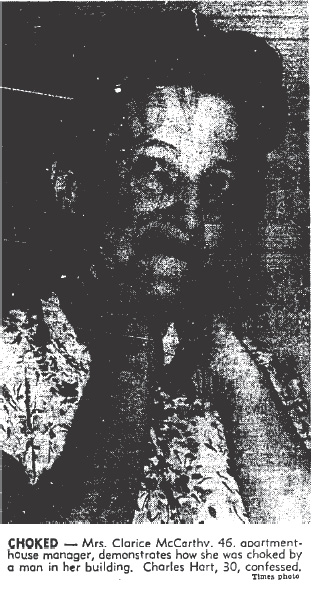

LAPD Motorcycle Officer Robert Knight found the suspect in the vicinity of Clarice’s apartment shortly after the attack. Detectives Jack McCreadie and S.W. Beckner of the central homicide squad said that the attacker, identified as 30-year-old Charles Hart of

LAPD Motorcycle Officer Robert Knight found the suspect in the vicinity of Clarice’s apartment shortly after the attack. Detectives Jack McCreadie and S.W. Beckner of the central homicide squad said that the attacker, identified as 30-year-old Charles Hart of  The records search turned up the names of three possible suspects; although only one of them, a 37-year-old ex-con named Clifford Russell Pridemore, was arrested. LAPD picked him up near

The records search turned up the names of three possible suspects; although only one of them, a 37-year-old ex-con named Clifford Russell Pridemore, was arrested. LAPD picked him up near

A couple of weeks following Karil Graham’s murder police announced they were investigating the slugging of Emily Jones, 26, a local dance hall hostess. Jones had awakened in her apartment at

A couple of weeks following Karil Graham’s murder police announced they were investigating the slugging of Emily Jones, 26, a local dance hall hostess. Jones had awakened in her apartment at

Karil Graham, an attractive divorcee in her late 30s, had always wanted to be an artist. She studied fine art in New York, but eventually she realized that she didn’t possess the natural talent to have a successful career. Unwilling to completely give up on her dream, Karil found a great way to be involved in what she loved most–she became the registrar at Art Center School, 5353 West 3rd Street. She spent much of her working day counseling budding artists, and the rest of her time in the company of talented faculty members. Karil had a warm smile that lit up her face. She was so well liked by the students that she was thought of as their “mother confessor”.

Karil Graham, an attractive divorcee in her late 30s, had always wanted to be an artist. She studied fine art in New York, but eventually she realized that she didn’t possess the natural talent to have a successful career. Unwilling to completely give up on her dream, Karil found a great way to be involved in what she loved most–she became the registrar at Art Center School, 5353 West 3rd Street. She spent much of her working day counseling budding artists, and the rest of her time in the company of talented faculty members. Karil had a warm smile that lit up her face. She was so well liked by the students that she was thought of as their “mother confessor”. Karil had a midnight snack and then prepared to go to bed. She removed her makeup, slipped into her nightgown and put her hair up in curlers. Then she turned on the electric blanket and got into bed.

Karil had a midnight snack and then prepared to go to bed. She removed her makeup, slipped into her nightgown and put her hair up in curlers. Then she turned on the electric blanket and got into bed. Los Angeles Police Department homicide detectives, Jack McCreadie and Charles Detrich, arrived and tried to make sense of the scene. Karil had sustained at least two devastating wounds to her head, but no weapon was found. During their examination of the crime scene they discovered a bloody fingerprint on the inside of the front doorknob. The knob was removed and sent to the crime lab, along with human hair found under one of Karil’s fingernails.

Los Angeles Police Department homicide detectives, Jack McCreadie and Charles Detrich, arrived and tried to make sense of the scene. Karil had sustained at least two devastating wounds to her head, but no weapon was found. During their examination of the crime scene they discovered a bloody fingerprint on the inside of the front doorknob. The knob was removed and sent to the crime lab, along with human hair found under one of Karil’s fingernails.