Ewing wasn’t concerned by Evelyn’s disappearance. Fiercely independent, she was known to go her own way, and that is what he told her friends that she had done.

Whenever her friends expressed their uneasiness about her sudden, mysterious departure Ewing would tell them that she had been drinking heavily and one night, in a drunken snit, she stood in their bedroom clutching a bottle of whisky and shouted obscenities at him. He claimed that Evelyn’s drinking was out of control.

Ewing Scott hides his face.

Evelyn’s friends were dumbfounded, and doubtful, of Ewing’s description of his wife’s behavior. A drunken, foul-mouthed Evelyn was simply inconceivable to them. There was nothing in her past that suggested she would behave that way under any circumstances. Contrarily, she was known to be ladylike and charming.

Two weeks following Evelyn’s disappearance, Ewing informed her chauffeur and handyman, Frank Justice, that his services were no longer required. Frank had worked for Evelyn since 1943 and was stunned that he was being let go. Ewing handed him a check for $100 and explained that he was taking Evelyn east because he was “discouraged with the way the doctors were making no headway with her diagnosis.” Ewing also told Frank that the only thing the doctors had decided was that Evelyn did not have cancer but may instead have mental problems.

Whenever Evelyn’s friends inquired about her Ewing cut them off, telling them bluntly that Evelyn was suffering from cancer, though he never specified what form the disease had taken, and that it had been her decision to go off on her own to seek treatment. Again, Evelyn’s friends didn’t buy Ewing’s story, and if they had known what he had told Frank they would have been even more suspicious.

Evelyn had been gone less than a month when Ewing visited the Cunard Steamship office. He spoke to the manager, Frank Hannifer, about a trip around the world – for one. The proposed trip would cost $7,250 – nearly twice as much as the average man earned in a year in 1955. The trip never materialized, but Ewing did put down a deposit of $1700 for a trip to the West Indies.

For a man with a sick wife, Ewing didn’t appear to have a care in the world. In fact, he was acting like a bachelor.

In July, Ewing met Harriet Livermore and began to entertain her in the Bel-Air home. Harriet was the widow of Jesse Lauriston Livermore, a stock speculator known as “The Wolf of Wall Street.” Harriet and Jesse were married only 7 years before he committed suicide in 1940. He had suffered some reversals of fortune and in a suicide note left for Harriet he described himself as “unworthy of your love.”

Jesse Livermore

When Harriet asked about his marriage, Ewing had a ready explanation. He said that she had abruptly walked out on him. Harriet was curious as to how a woman could up and walk away like that. Ewing said that Evelyn was always prepared and routinely kept $18,000 on her person. That should have made Harriet’s eyes pop out on springs like a cartoon character, but obviously the rich have a much different idea of pocket change than the rest of us. Harriet got an earful about Evelyn from Ewing who said that his runaway wife was a chain smoker, an alcoholic and a lesbian. Ewing eagerly defamed his absent wife at every opportunity.

Harriet asked Ewing why, if Evelyn was so horrible, he hadn’t divorced her. He had an explanation for that, too. He said that all he had to do was wait for seven years and if Evelyn didn’t reappear he would be entitled to everything – money, property, the whole shebang. According to Ewing he could afford to wait. He had sold his property in Milwaukee (never letting on the property wasn’t his to sell) and that he was in a comfortable financial position. He then asked Harriet if she would accompany him on a trip around the world (but only if they went “Dutch Treat”); or to Guatemala. Harriet declined the invitations.

Mrs. Marianne Beaman, 46, Santa Monica dental assistant, explains to reporters how she met L. Ewing Scott, whose wife is missing mysteriously, and the subsequent dates she had with him.

While he was dating Harriet, Ewing met another woman – Marianne Beaman, with whom he also started keeping company. As he had done with Harriet, Ewing didn’t hesitate to air his dirty marital laundry. Evidently, Evelyn’s disappearance was a great strain on him. He said he thought, but wasn’t sure, that Evelyn had attempted to poison him. Then he walked that statement back a little and said that even if she hadn’t tried to do him in, the fact that he thought her capable of such a thing was indicative of her deteriorating mental condition. He didn’t have a shred of credible evidence that Evelyn had ever attempted to harm him.

According to their mutual acquaintances, Marianne and Ewing didn’t have a torrid love affair. Acquaintances described them as “two lonely people who enjoyed chatting together over a dinner table.” If dinner conversation lagged maybe Ewing would take the time to explain to his date why Wolfer Printing Company had a $6,000 judgement against him dating from 1953. The judgement had to do with a book project.

In 1953, Ewing met with William Good, vice president and general manager of Wolfer Printing Company at 416 South Wall Street in Los Angeles. Ewing had brought with him a manuscript, provocatively titled “How to Fascinate Men”. Ewing said the book had been written by a UCLA professor, Charles Contreras, whom he had met at the Jonathan Club. William had his doubts about the author, he had a gut feeling that Ewing had written the book himself. Not that it mattered.

Ewing ordered 10,000 copies of the book and a custom designed cover. The cover alone cost $750, and it featured a blonde who didn’t look like she’d need an instruction manual.

Ewing ordered 10,000 copies of the book and a custom designed cover. The cover alone cost $750, and it featured a blonde who didn’t look like she’d need an instruction manual.

When the book was ready, Ewing came and picked up 25 copies – then he disappeared. Wolfer Printing was stuck with 9975 copies of “How to Fascinate Men.”

Ewing’s carefully curated personality as man with financial acumen – a man worthy of his smart, capable and cultured wife – started to unravel.

Deftly juggling stories like a Barnum & Bailey circus performer, Ewing managed to keep Evelyn’s friends and acquaintances at bay for nearly a full year. During all that time no one, except Ewing – if you believed him – had any contact with Evelyn.

By March 6, 1956, Evelyn’s brother, Raymond Throsby, had had enough. He filed paperwork to become the trustee of her estate. James B. Boyle, who had been Evelyn’s attorney for over 20 years, had a copy of her will in his office safe, but he was adamant that he would not reveal its contents unless or until he was compelled by a court order.

It didn’t take long for things to heat up among the possible contenders for trustee. A three-way battle loomed on the horizon.

It didn’t take long for things to heat up among the possible contenders for trustee. A three-way battle loomed on the horizon.

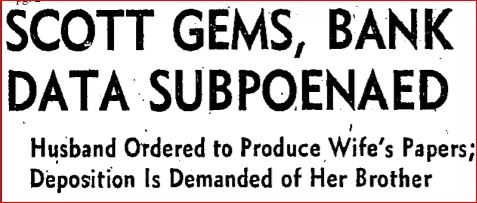

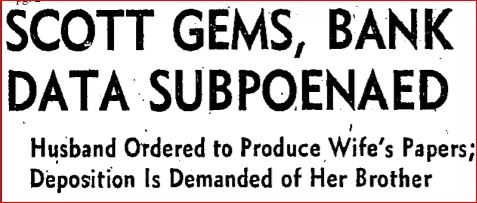

While Ewing waged war on the trustee front, his attorney attempted to fend off cops who wanted Ewing to submit to a lie detector test. And to add to his stress, Ewing was subpoenaed to get him to produce some of Evelyn’s jewels and papers.

Ewing was under increasing scrutiny in Evelyn’s disappearance. What would he do?

NEXT TIME: Ewing makes a move.

Ewing ordered 10,000 copies of the book and a custom designed cover. The cover alone cost $750, and it featured a blonde who didn’t look like she’d need an instruction manual.

Ewing ordered 10,000 copies of the book and a custom designed cover. The cover alone cost $750, and it featured a blonde who didn’t look like she’d need an instruction manual. It didn’t take long for things to heat up among the possible contenders for trustee. A three-way battle loomed on the horizon.

It didn’t take long for things to heat up among the possible contenders for trustee. A three-way battle loomed on the horizon.