Bundled up against the chill of a cold wave that had held Los Angeles residents in its grip for several days, Mrs. Betty Bersinger and her three-year-old daughter Anne walked south on the west side of Norton in Leimert Park, a Los Angeles suburb. Midway down the block, Bersinger noticed something pale in the weeds about fifty feet north of a fire hydrant and about a foot in from the sidewalk.

Initially, Bersinger believed she was seeing a discarded mannequin or a passed-out nude woman.

It took a moment before Bersinger realized she was in a waking nightmare. The bright white shape in the weeds was neither a mannequin nor a drunk.

Bersinger later recalled, “I was terribly shocked and scared to death. I grabbed Anne, and we walked as fast as we could to the first house that had a telephone.”

Over the years, several reporters have claimed to have been first on the scene of the murder. One person who made that claim was Will Fowler.

Fowler said he and photographer Felix Paegel of the Los Angeles Examiner approached Crenshaw Boulevard when they heard an intriguing call on their shortwave radio. It was a police call and Fowler couldn’t believe his ears. A naked woman, possibly drunk, was found in a vacant lot one block east of Crenshaw between 39th and Coliseum streets. Fowler turned to Pagel and said, “A naked drunk dame passed out in a vacant lot. Right here in the neighborhood too… Let’s see what it’s all about.”

Paegel drove as Fowler watched for the woman. “There she is. It’s a body all right…” Fowler hopped out of the car and approached the woman as Paegel pulled his Speed Graphic from the trunk. Fowler called out, “Jesus, Felix, this woman’s cut in half!”

That was Fowler’s story, and he stuck to it through the decades. He said he closed the dead girl’s eyes. But was his story true?

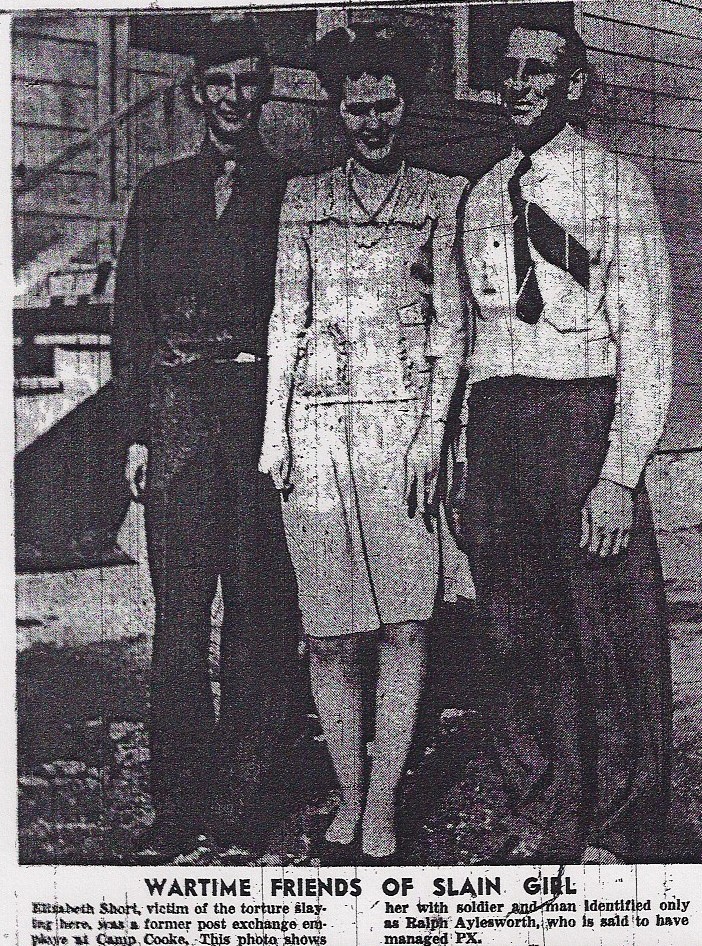

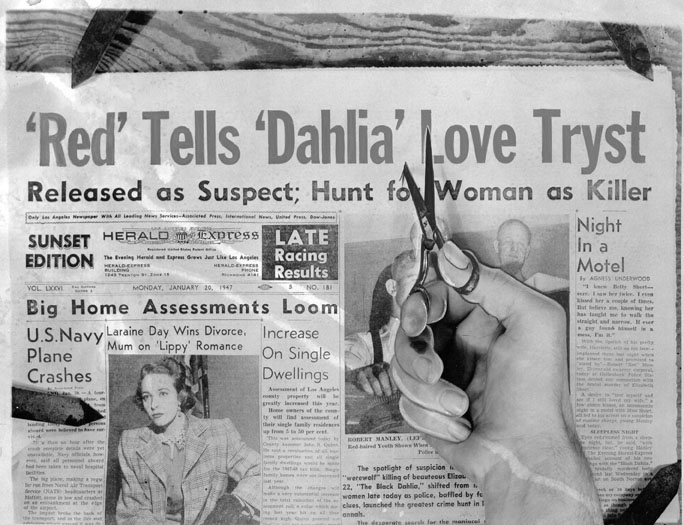

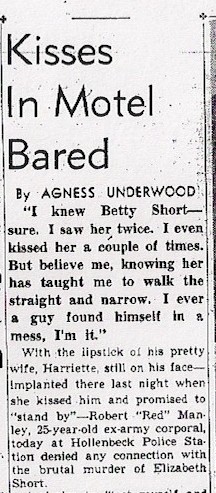

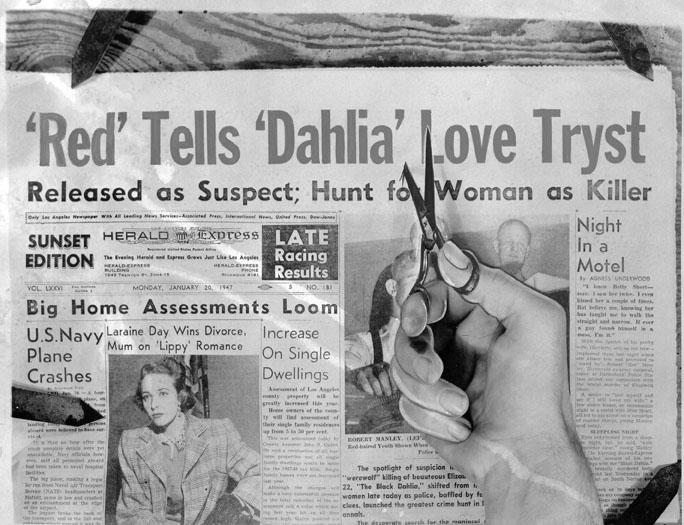

There is information to suggest that a reporter from the Los Angeles Times was the first on the scene; and in her autobiography, Newspaperwoman, Aggie Underwood, said that she was the first.

After 78-years does it really matter? All those who saw the murdered girl that day saw the same horrifying scene, and it left an indelible impression. Aggie described what she observed:

“It [the body] had been cut in half through the abdomen, under the ribs. The two sections were ten or twelve inches apart. The arms, bent at right angles at the elbows, were raised about the shoulders. The legs were spread apart. There were bruises and cuts on the forehead and the face, which had been beaten severely. The hair was blood-matted. Front teeth were missing. Both cheeks were slashed from the corners of the lips almost to the ears. The liver hung out of the torso, and the entire lower section of the body had been hacked, gouged, and unprintably desecrated. It showed sadism at its most frenzied.”

Two seasoned LAPD detectives, Harry Hansen and Finis Brown, took charge of the investigation. During the first twenty-four hours, officers pulled in over 150 men for questioning.

The most promising of the early suspects was a twenty-three-year-old transient, Cecil French. He was busted for molesting women in a downtown bus depot.

Police were further alarmed when they discovered French had pulled the back seat out of his car. Had he concealed a body there? Police Chemist Ray Pinker found no blood or any other physical evidence of a bloody murder in French’s car. He was dropped from the list of hot suspects.

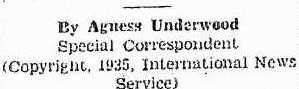

c. 1935 Photo courtesy LAPL

In her initial coverage, Aggie referred to the case as the “Werewolf” slaying because of the savagery of the mutilations inflicted on the unknown woman. Aggie’s werewolf tag would identify the case until a much better one was discovered—the Black Dahlia.

REFERENCES:

Fowler, Will (1991). “Reporters” Memoirs of a Young Newspaperman.

Gilmore, John (2001). Severed: The True Story of the Black Dahlia Murder.

Harnisch, Larry. “A Slaying Cloaked in Mystery and Myths.” Los Angeles Times. January 6, 1997.

Underwood, Agness (1949). Newspaperwoman.

Wagner, Rob Leicester (2000). The Rise and Fall of Los Angeles Newspapers 1920-1962.