By December 1927 twenty-three-year-old Ruth Malone had been in Los Angeles for about 4 months. She’d fled Aberdeen, Washington to escape her husband John, a jealous and violent drunk. She used her mother’s address at 244 North Belmont Avenue, but lived with a girl friend in an apartment at 9th and Flower. She kept the address of the apartment a secret just in case John tried to find her. She worked half a mile from the apartment at a drug store on East Twelfth between Santee Street and Maple Avenue. Ruth had spent the last few months seriously contemplating divorce but she wasn’t in any hurry to confront John.

By December 1927 twenty-three-year-old Ruth Malone had been in Los Angeles for about 4 months. She’d fled Aberdeen, Washington to escape her husband John, a jealous and violent drunk. She used her mother’s address at 244 North Belmont Avenue, but lived with a girl friend in an apartment at 9th and Flower. She kept the address of the apartment a secret just in case John tried to find her. She worked half a mile from the apartment at a drug store on East Twelfth between Santee Street and Maple Avenue. Ruth had spent the last few months seriously contemplating divorce but she wasn’t in any hurry to confront John.

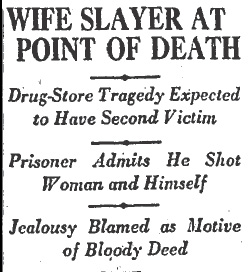

It was 11 o’clock on the morning of Wednesday, December 7, 1927 and Ruth had started her work day when John turned up. She hadn’t even known he was in town. He was obviously drunk and made a scene. He wanted Ruth to come back to him, but she wasn’t interested in a reconciliation and John stormed out. He returned at noon and began to plead with Ruth. Again she accused him of being drunk. He copped to it–in fact he said that he’d been drinking for three weeks straight and would stay drunk until Ruth agreed to come back to him. She refused. He pulled a revolver from his pocket. Ruth clocked it and made a dash for the rear of the store. Her escape route was cut off by some partitions–she was trapped. As twenty people watched John began firing and each shot hit its mark. Ruth was hit in the chest, face and hip. Satisfied that he’d killed her, John turned the gun on himself. One bullet entered his chest a few inches above his heart and then he raised the weapon to his head and fired.

The police were called and when Detectives Lieutenants Hickey, Stevens and Condaffer, of the LAPD’s Central Station Homicide Squad arrived they found Ruth dead and John nearly so. Detective Hickey was shocked when John summoned the strength to say “I’m sorry I killed her, but give me a smoke before I croak, will you?” Hickey later said that even though John believed he was dying his first thought appeared to be of a cigarette. The detectives also found an incoherent note in John’s pocket, the ramblings of a man driven to murder by jealousy and gin.

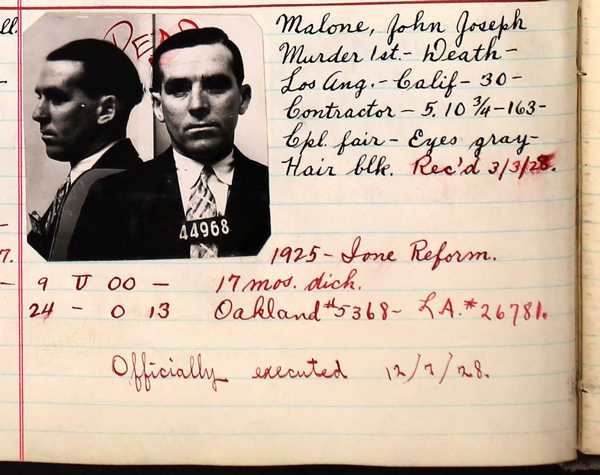

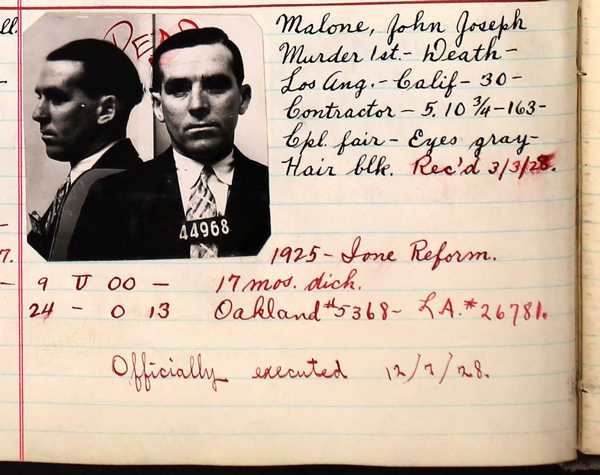

Investigators learned that John was 29-years-old and that he had an arrest record. He’d been busted in Oakland on October 10, 1917 on a burglary charge and later in San Francisco for violation of the State Poison Act (a drug charge). John had been in Los Angeles for a few weeks. He was staying at a hotel just a few blocks away from Ruth’s workplace.

Investigators learned that John was 29-years-old and that he had an arrest record. He’d been busted in Oakland on October 10, 1917 on a burglary charge and later in San Francisco for violation of the State Poison Act (a drug charge). John had been in Los Angeles for a few weeks. He was staying at a hotel just a few blocks away from Ruth’s workplace.

As John lay in a bed in General Hospital fighting for his life, a Coroner’s jury charged him with Ruth’s slaying. If he lived he would be tried for her murder. Ruth was buried in Graceland Cemetery following a private funeral at Mead & Mead undertaking parlor.

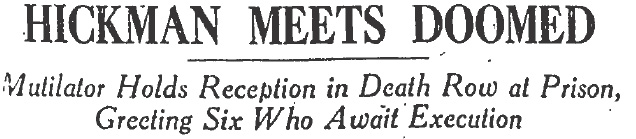

It was touch and go for a few weeks but John pulled through and by February 1928 he was well enough to stand trial. L.V. Beaulieu, his court-appointed attorney, unsuccessfully attempted to use John’s three week long drinking spree as an excuse for the murder but the judge sustained the prosecution’s objections. Alcohol induced amnesia was a poor defense strategy. The jury quickly returned a guilty verdict with no recommendation for leniency. Under the law Judge Fricke had no alternative but to sentence John to be hanged. He was transported to San Quentin to await execution. On March 20, 1928 John and several other death row inmates welcomed a newcomer to their ranks, William Edward Hickman. Hickman, who had given himself the nickname “The Fox” had been sentenced to death for the brutal mutilation murder of 12-year-old Marion Parker, a crime he had committed only ten days after John had killed Ruth. The two dead men walking had met in the Los Angeles County Jail while each was awaiting trial. John cornered Hickman on one occasion and blamed him for inciting the public to a renewed interest in capital punishment–resulting in his own date with the hangman.

On March 20, 1928 John and several other death row inmates welcomed a newcomer to their ranks, William Edward Hickman. Hickman, who had given himself the nickname “The Fox” had been sentenced to death for the brutal mutilation murder of 12-year-old Marion Parker, a crime he had committed only ten days after John had killed Ruth. The two dead men walking had met in the Los Angeles County Jail while each was awaiting trial. John cornered Hickman on one occasion and blamed him for inciting the public to a renewed interest in capital punishment–resulting in his own date with the hangman.

John’s sentence was automatically appealed but the State Supreme Court upheld the death penalty. Judge Fricke re-sentenced John to hang. Unless something changed he would meet his end on December 7, exactly one year to the day since Ruth’s murder. John had evidently changed his mind about dying since his suicide attempt because he was part of a Thanksgiving escape plot that failed. To prevent him from any further attempts to tunnel out of San Quentin he was moved to the death cell.

John’s sentence was automatically appealed but the State Supreme Court upheld the death penalty. Judge Fricke re-sentenced John to hang. Unless something changed he would meet his end on December 7, exactly one year to the day since Ruth’s murder. John had evidently changed his mind about dying since his suicide attempt because he was part of a Thanksgiving escape plot that failed. To prevent him from any further attempts to tunnel out of San Quentin he was moved to the death cell.

As a condemned man, John’s final requests were honored. He was given a record player and listened repeatedly to “I Want to Go Where You Go” until it was time for him to climb the thirteen steps to the scaffold. One year before, just moments after killing Ruth, John’s first thought had been for a cigarette. Nothing had changed in the year since. John was still smoking as guards placed the black cap over his head. As he dropped he quipped: “Well boys, I got a run for this one.” The cigarette was jerked from his lips. Three witnesses, one of them a guard, fainted. John Joseph Malone was pronounced dead 12 minutes later.

Jealously and gin make a lethal cocktail.

By December 1927 twenty-three-year-old Ruth Malone had been in Los Angeles for about 4 months. She’d fled Aberdeen, Washington to escape her husband John, a jealous and violent drunk. She used her mother’s address at 244 North Belmont Avenue, but lived with a girl friend in an apartment at 9th and Flower. She kept the address of the apartment a secret just in case John tried to find her. She worked half a mile from the apartment at a drug store on East Twelfth between Santee Street and Maple Avenue. Ruth had spent the last few months seriously contemplating divorce but she wasn’t in any hurry to confront John.

By December 1927 twenty-three-year-old Ruth Malone had been in Los Angeles for about 4 months. She’d fled Aberdeen, Washington to escape her husband John, a jealous and violent drunk. She used her mother’s address at 244 North Belmont Avenue, but lived with a girl friend in an apartment at 9th and Flower. She kept the address of the apartment a secret just in case John tried to find her. She worked half a mile from the apartment at a drug store on East Twelfth between Santee Street and Maple Avenue. Ruth had spent the last few months seriously contemplating divorce but she wasn’t in any hurry to confront John.

Investigators learned that John was 29-years-old and that he had an arrest record. He’d been busted in Oakland on October 10, 1917 on a burglary charge and later in San Francisco for violation of the State Poison Act (a drug charge). John had been in Los Angeles for a few weeks. He was staying at a hotel just a few blocks away from Ruth’s workplace.

Investigators learned that John was 29-years-old and that he had an arrest record. He’d been busted in Oakland on October 10, 1917 on a burglary charge and later in San Francisco for violation of the State Poison Act (a drug charge). John had been in Los Angeles for a few weeks. He was staying at a hotel just a few blocks away from Ruth’s workplace. On March 20, 1928 John and several other death row inmates welcomed a newcomer to their ranks, William Edward Hickman. Hickman, who had given himself the nickname “The Fox” had been sentenced to death for the brutal mutilation murder of 12-year-old Marion Parker, a crime he had committed only ten days after John had killed Ruth. The two dead men walking had met in the Los Angeles County Jail while each was awaiting trial. John cornered Hickman on one occasion and blamed him for inciting the public to a renewed interest in capital punishment–resulting in his own date with the hangman.

On March 20, 1928 John and several other death row inmates welcomed a newcomer to their ranks, William Edward Hickman. Hickman, who had given himself the nickname “The Fox” had been sentenced to death for the brutal mutilation murder of 12-year-old Marion Parker, a crime he had committed only ten days after John had killed Ruth. The two dead men walking had met in the Los Angeles County Jail while each was awaiting trial. John cornered Hickman on one occasion and blamed him for inciting the public to a renewed interest in capital punishment–resulting in his own date with the hangman. John’s sentence was automatically appealed but the State Supreme Court upheld the death penalty. Judge Fricke re-sentenced John to hang. Unless something changed he would meet his end on December 7, exactly one year to the day since Ruth’s murder. John had evidently changed his mind about dying since his suicide attempt because he was part of a Thanksgiving escape plot that failed. To prevent him from any further attempts to tunnel out of San Quentin he was moved to the death cell.

John’s sentence was automatically appealed but the State Supreme Court upheld the death penalty. Judge Fricke re-sentenced John to hang. Unless something changed he would meet his end on December 7, exactly one year to the day since Ruth’s murder. John had evidently changed his mind about dying since his suicide attempt because he was part of a Thanksgiving escape plot that failed. To prevent him from any further attempts to tunnel out of San Quentin he was moved to the death cell.