For the past 3 1/2 years I’ve been a volunteer archivist at the Los Angeles Police Museum. I find the work fascinating and rewarding, in fact given my passion for old paper (I have a vast collection of vintage cosmetics ephemera) and historic L.A. crime, it is the ideal place for me.

When I first met with the Executive Director of the LAPM, I wasn’t sure what projects they had or what they would want me to do. I told him about my personal collection and he said “I may have a project for you.” He sure did! He showed me the museum’s collection of Daily Bulletins and I was immediately hooked.

Many of the Daily Bulletins had been bound into volumes, while others were loose pages. The majority of the Bulletins, even those in bindings, were in fragile condition. They were printed on inexpensive paper and were handed out to each officer at the beginning of a shift; they were never meant to survive beyond a day or two and we wanted them to last forever.

Our first priority was to determine the best practice for preserving the Bulletins — they’re a valuable resource and we couldn’t afford to make any mistakes.

We we arranged a consultation with experts at the Getty and they recommended that we unbind the volumes and place the individual pages into archival sleeves.

I was particularly worried about the unbinding process. I’d never done anything like it before. With proper instruction and the right tools I have been able to unbind many years worth of Daily Bulletins. The future of the Bulletins is secure, and we’ll eventually have a searchable database which will allow us to further our own research as well as to share knowledge with historians, sociologists, criminologists and policy makers.

The Bulletins began in March of 1907 under Chief Edward Kerr, and provide a daily snapshot of the LAPD as well as of the City of Los Angeles over a period of 50 years.

In his 1913 holiday greeting, Chief C.E. Sebastian referred to the Daily Bulletin as the ‘Paper Policeman’, which suits them perfectly. The Bulletins didn’t just convey information about wanted criminals or stolen property; they contained notices of funerals, commendations, and policy and procedure updates.

The Bulletins sometimes had a sense of humor. In this Bulletin from April 1, 1907 there’s a LOOK OUTS notice:

“A real bear is lost, strayed or stolen from the Shrine Sircus (sic) at Fiesta Park. Look out for him and if found notify Leo Youngworth, U.S. Marshal and Chief Bear Tamer.”

I checked the historic LA Times and there was a circus in town that week, but I found no report of a runaway bear.

Dedication of the L.A. Aqueduct — November 5, 1913. [Photo courtesy of LAPL]

The November 3, 1913 Daily Bulletin listed the all of the officers who would form the Aqueduct Detail for the opening of the Los Angeles Aqueduct.

It was arguably the most significant event in the history of L.A., and the Bulletin shows that LAPD was present.

It was arguably the most significant event in the history of L.A., and the Bulletin shows that LAPD was present.

I’ve seen thousands of incredible Daily Bulletins, but the one that means the most to me personally is from June 1953, and that’s because I was peripherally involved in the cold case 56 years later.

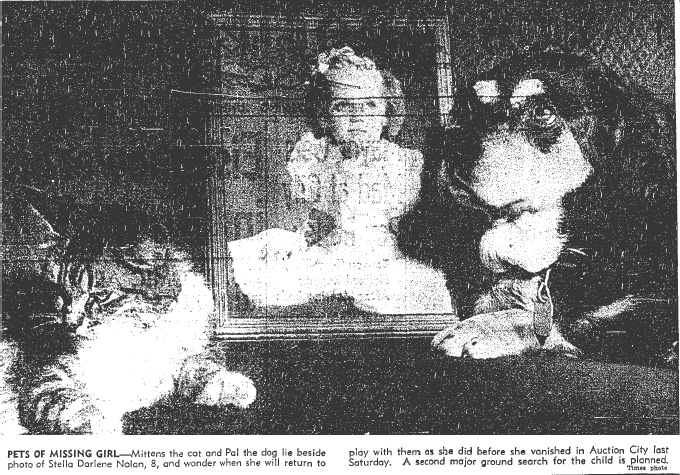

But let me begin at the beginning — June 20, 1953. Ilene Nolan had reported the disappearance, and possible abduction, of her eight year old daughter, Stella Darlene. There was something about the little girl that caught my eye.

Usually a missing child will turn up in a day or two and the notice will be canceled in a subsequent Bulletin. I couldn’t find a cancellation for Stella, so I decided to dig deeper; and I couldn’t believe what I found.

Stella had disappeared from Auction City (in the Norwalk area) where her mother was employed as a clerk at a refreshment stand. Stella was a well behaved child and checked in every hour with her mom, so when she failed to turn up between 8 and 9 pm Mrs. Nolan knew that something was wrong.

Stella had disappeared from Auction City (in the Norwalk area) where her mother was employed as a clerk at a refreshment stand. Stella was a well behaved child and checked in every hour with her mom, so when she failed to turn up between 8 and 9 pm Mrs. Nolan knew that something was wrong.

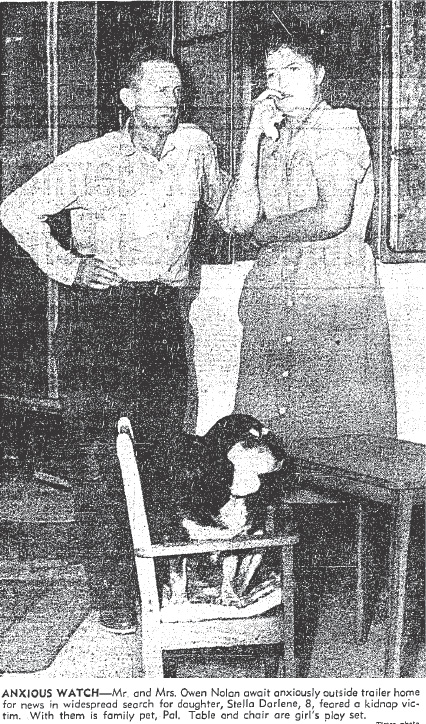

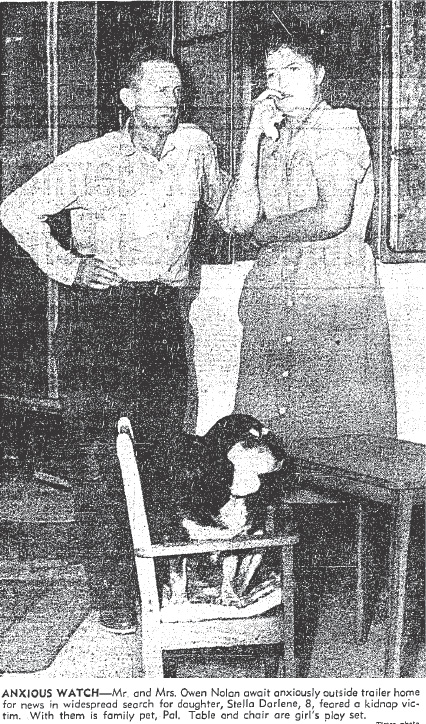

A few days following Stella’s disappearance the little girl had still not returned home. Her parents, who lived in a trailer park at 16108 South Atlantic in Compton, were frantic with worry. Even Stella’s dog, Pal, was inconsolable. By day, the little dog wandered around the trailer whimpering, and at night he would howl and bay.

A few days following Stella’s disappearance the little girl had still not returned home. Her parents, who lived in a trailer park at 16108 South Atlantic in Compton, were frantic with worry. Even Stella’s dog, Pal, was inconsolable. By day, the little dog wandered around the trailer whimpering, and at night he would howl and bay.

In desperation, Stella’s mom and dad revealed that they were not her birth parents and that even though they’d had custody of her since birth they had never legally adopted her!

Ilene told cops how she and her husband, Owen, had acquired custody of Stella. During the mid-1940s Ilene had worked with Marjorie Woods and Betty Jean Stalcup at the Pony Cafe in San Diego. Ilene had expressed her desire to have a child and so Betty Jean, who was pregnant, agreed to give her baby to Nolan a few days after the baby’s birth. Six days after the child was born Betty Jean tuned her over to Ilene.

The Nolans said they had often thought of adopting Stella Darlene and in 1950 they had even gone so far as to consult a San Diego lawyer. The attorney, however, had advised the couple to save possible sorrow and heartbreak by doing nothing!

The cops quickly located Betty Jean, Stella’s birthmother. She’d moved to Texas, married, and had a three year old girl. She was swiftly cleared of any involvement in Stella’s disappearance.

The newspapers reported that except for occasional fits of silent weeping, Ilene Nolan had maintained her composure. But she lost it when her cousin, Mrs. Kay Talley of San Diego, arrived at the trailer. Ilene collapsed and sobbed convulsively. Then she told of having a vision in which she saw Stella Darlene dead.

She said:

“I sat quiet for a few minutes trying to rest. I was thinking very hard about anything that might help us. Then across my eyes came a vision of Darlene’s little legs sticking out of a hole somewhere. She had red shoes on her feet. They were leather ones with big, thick crepe rubber soles.”

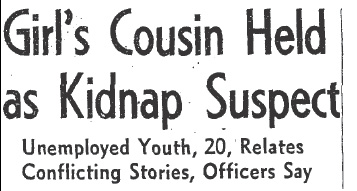

By early July, barely a month after she’d disappeared, Stella’s twenty year old married cousin, William R. Nolan, an unemployed hospital orderly, was jailed on a technical booking in Long Beach as a key suspect in the case. Nolan emphatically denied any connection with Stella Darlene’s disappearance. William was grilled for hours by detectives. The L.A. Sheriff’s Department dispatched several criminal laboratory technicians to check for possible blood stains in William’s bungalow court apartment and in the trunk of his 1949 convertible. The techs didn’t turn up a single clue. He told conflicting stories regarding his whereabouts on the night that Stella disappeared, but he was cleared.

At least one crank caller phoned the Nolans to tell them that their little girl was alive, but nothing came of the call. The police were frustrated by the lack of movement in the case.

In mid-October 1953, a fourteen year old boy was brought in for questioning — Norwalk Dep. Dist Atty. Adolph Alexander and Inspector Garner Brown stated that the boy held the key to the girl’s fate. While the fourteen year old was being questioned two of his acquaintances, William R. Hardy, twenty-two, and an unnamed seventeen year old, were facing lie detector tests in Pasadena.

In mid-October 1953, a fourteen year old boy was brought in for questioning — Norwalk Dep. Dist Atty. Adolph Alexander and Inspector Garner Brown stated that the boy held the key to the girl’s fate. While the fourteen year old was being questioned two of his acquaintances, William R. Hardy, twenty-two, and an unnamed seventeen year old, were facing lie detector tests in Pasadena.

The boys were proved to be liars, and one of them even made a false confession, however they were not killers.

During the remainder of 1953 various “hot” suspects were interrogated but none of them panned out.

On June 20, 1955, the second anniversary of her disappearance, the L.A. Times ran a follow-up story about Stella but it didn’t result in any further leads. The Sheriff’s detectives reluctantly stated that they believed Stella had been kidnapped and killed by a sexual psychopath.

Mrs. Nolan told reporters:

“We’ll never give up hope until we’re both dead.”

NEXT TIME: What happened to Stella Darlene Nolan?

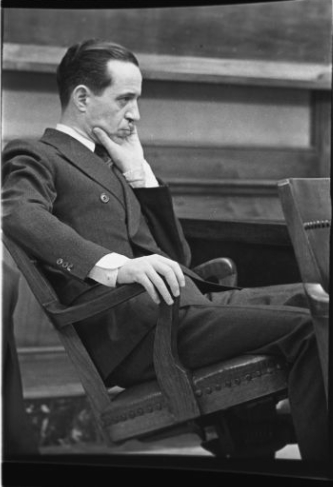

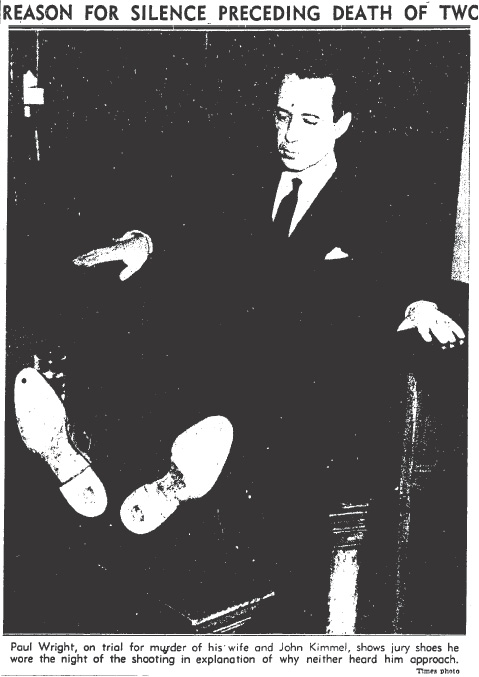

![Paul Wright in court. [Photo courtesy of UCLA digital collection.]](https://derangedlacrimes.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/05/paul-wright_ucla-collection.jpg)

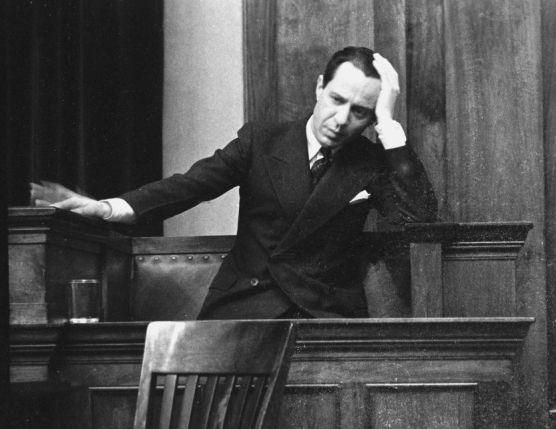

![Paul Wright & Jerry Giesler [Photo courtesy UCLA digital collection.]](https://derangedlacrimes.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/05/wright_geisler_ucla-photo.jpg)

![Bugsy Siegel and Jerry Geisler. [Photo courtesy of LAPL.]](https://derangedlacrimes.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/05/00010116_geisler_siegel.jpg)