Reporter Aggie Underwood devoted a chapter in her 1949 autobiography, Newspaperwoman, to movie stars. One star she covered was Thelma Todd. Thelma, nicknamed the Ice Cream Blonde, was a popular actress appearing in over 120 films between 1926 and 1935.

Thelma was born on July 29, 1906, in Lawrence, Massachusetts. She excelled in her studies and aspired to be a schoolteacher. Despite going to college after high school, her mother still pushed her to take part in beauty contests because of her looks. In 1925, she became “Miss Massachusetts” and entered the “Miss America” pageant. Despite not winning, Hollywood talent scouts took notice of her.

Among the stars with whom Thelma appeared during her career were Gary Cooper, William Powell, The Marx Brothers, and Laurel and Hardy.

In the late 1920s and early 1930s, various male comedy duos achieved success. Studio head Hal Roach saw the potential in pairing two women. Between 1931 and 1933 Thelma and Zasu Pitts appeared in over a dozen films, primarily two-reelers.

When it came time for contract renegotiation, Zasu and Thelma found out that Hal Roach had made certain that their individual contracts expired six months apart. He concluded the stars had less leverage individually than they would as a team. He’d pulled the same trick on Laurel and Hardy. Zasu’s bid for more money and a stake in the team’s films was a non-starter with Roach. They gave her a take it or leave it option. She left. Thelma’s new partner was wisecracking Patsy Kelly, and they churned out a series of successful shorts for Roach until 1935.

Thelma’s pleasant voice made her transition from silent to sound films an easy one. She had name recognition and with financial backing from her lover, film director Roland West, she opened the Thelma Todd’s Sidewalk Café. Thelma and Roland lived in separate rooms above the café. They had known each other for about 5 years. Thelma starred in West’s 1931 film Corsair, and that is when they embarked on a passionate affair.

West’s estranged wife, Jewel Carmen, lived in a home about 300 feet above the café on a hill overlooking the Pacific Ocean. It was an odd domestic arrangement, to be sure.

On Saturday, December 14, 1935, Thelma’s personal maid of four years, May Whitehead, helped to dress the actress in a blue and silver sequin gown for a party. At about 8 p.m. Thelma and her mother Alice were preparing to leave the Café together. Thelma had plans to attend a party at the Trocadero, where Ida Lupino and her father Stanley were the hosts.

As they were about to get into the limo driven by Ernie Peters (one of Thelma’s regular drivers) Roland approached Thelma and told her to be home by 2 a.m. Not one to be given orders, Thelma said she’d be home at 2:05.

When questioned later, West described his exchange with Thelma as more of a joke than a serious demand on his part. On that earlier occasion, Thelma had knocked hard enough to break a window and Roland let her in.

According to party goers, Thelma arrived at the Trocadero in high spirits and seemed to look forward to the holidays. She downed a few cocktails. Although intoxicated, none of her friends thought she was drunk. Thelma’s ex-husband, Pat Di Cicco, was at the Trocadero with a date, but he was not a guest at the Lupino’s party.

Very late in the evening, Thelma joined Sid Grauman’s table for about 30 minutes before asking him if he’d call Roland and let him know she was on her way home. Thelma’s chauffeur said that the actress was unusually quiet on the ride home, and when they arrived, she declined his offer to walk her to the door of her apartment. He said she’d never done that before.

It’s at this point that the mystery of Thelma Todd’s death begins.

On Monday, December 16, 1935, May Whitehead, had driven her own car to the garage, as she did every morning, to get Thelma’s chocolate brown, twelve-cylinder Lincoln phaeton and bring it down the hill to the café for Thelma’s use.

May said that the doors to the garage were closed, but unlocked. She entered the garage and saw the driver’s side door to Thelma’s car was wide open. Then she saw Thelma slumped over in the seat. At first May thought Thelma was asleep, but once she realized her employer was dead, she went to the Café and notified the business manager and asked him to telephone Roland West.

Once Thelma Todd’s premature death became public, local newspapers sensationalized it, hinting at foul play. The Daily Record’s headline proclaimed: “THELMA TODD FOUND DEAD, INVESTIGATING POSSIBLE MURDER”. The Herald’s cover story suggested that Todd’s death was worthy of Edgar Allan Poe:

“…if her death was accidental, it was as strange an accident as was ever conceived by the brain of Poe.”

The circumstances of Thelma’s death were puzzling, and upon receiving the news, her mother, Alice Todd, shrieked, “My daughter has been murdered!”

Whether Thelma’s death was a suicide, accident, or murder rested with the cops and criminalists. Thelma’s face bore traces of blood, and droplets of blood were present inside the car and on the running board.

According to the coroner, Thelma’s death likely occurred around twelve hours before they found her body. But a few witnesses came forward to swear that they’d seen, or spoken to, Thelma on Sunday afternoon when, according to the coroner, she would have already been dead.

The most interesting of the witnesses who had claimed to have seen or spoken with Thelma on Sunday was Mrs. Martha Ford. She and her husband, the actor Wallace Ford, were hosting a party that day to which they had invited Todd. She said that she received a telephone call and that she’d at first thought the caller was a woman named Velma, who she was expecting at the party; but then the caller identified herself as Thelma, and used the nickname Hot Toddy. Martha said that Toddy asked her if she could show up in the evening clothes she’d worn the night before to a party — Martha told her that was fine. “Toddy” also said she was bringing a surprise guest and said, “You just wait until I walk in. You’ll fall dead!” Mrs. Ford insisted the caller was Thelma.

Thelma Todd’s death evoked a massive outpouring of grief. Hundreds of mourners from all walks of life visited Pierce Mortuary where Thelma’s body was on view from 8:00 a.m. to 1:00 p.m. on December 19, 1935.

Patsy Kelly was said to have been so upset that she was under a doctor’s care. Thelma’s death devastated Zasu Pitts. She had been out Christmas shopping with her a few days earlier.

The sightings of Thelma on Sunday led to a multitude of theories, ranging from plausible to crackpot. Among the theories that have gained popularity over the years, even though unsubstantiated, is the rumor New York mobster Lucky Luciano put pressure on Thelma to host gambling at the Café. When Thelma said no, he had her killed.

Another theory is her ex-husband, Pat Di Cicco, murdered Thelma. He had a history of violence against women; but they found no evidence against him.

I have my own theory, of course. How could I not? Here’s what I believe happened.

On Saturday night as she was leaving for the Trocadero, Roland West told Thelma to be home at 2 am. He wasn’t joking with her as he’d said. Asserting herself, she told him she’d be home at 2:05—but at 2:45 or 3 a.m., probably to avoid an unplkeasant call, she asked Sid Grauman to phone West and let him know she was on her way.

Her chauffeur, Ernie, said they arrived at the café at about 3:30 a.m. and she declined his offer to walk her up to her apartment. I believe she declined because she expected an ugly scene with Roland about her late arrival home. She had a key in her evening bag, but the door to the apartment was bolted from the inside. Roland had locked her out again. She was tired, and she’d been drinking. Her blood alcohol level was later found to be .13, enough for her to be intoxicated but not sloppy drunk. She decided she didn’t have the energy to engage in an argument with Roland—it must have been about 4 am. The beach was cold that night as Thelma trudged up the stairs to the garage.

After opening the garage doors, she turned on the light. To stay warm, she started her car and turned on the engine. Within minutes, she fell asleep and succumbed to carbon monoxide poisoning. She fell over and banged her head against the steering wheel of the car, which caused a small amount of blood to be found on her body. Later, they tested the blood and found carbon monoxide in it, indicating that her injury happened inside the garage.

According to tests made by criminalist Ray Pinker, it would have taken about two minutes for there to have been enough carbon monoxide in the garage to kill her. He had even tested the car to see how long it would run before the engine died—the shortest time it idled was 2 minutes 40 seconds, the longest was 46 minutes 40 seconds.

What about the light switch and the open car door? I think that when Roland heard nothing from Thelma, he looked for her. He walked to the garage to see if she’d taken her car. He went inside and saw Thelma slumped over in the front seat, just the way May Whitehead would find her on Monday morning. The car’s motor was no longer running. He opened the driver’s side door to wake her up, only to discover she was dead. Shocked, he left, leaving the driver’s side door open, switching off the garage light and closing the doors. Then he returned to the apartment.

While West did not kill Thelma, I believe he felt responsible for her death. He never told a soul about that night; unless you believe the rumor that he made a death bed confession to his friend, actor Chester Morris.

What about Martha Ford’s alleged telephone conversation with Thelma? Was it Thelma on the phone? Maybe Ford was mistaken about the time. Another of the many loose ends in the mystery surrounding Thelma’s death.

Aggie was wrapping up her first year as a reporter for Hearst when Thelma Todd died. She had never attended an autopsy before. She knew her male colleagues brought her along to test her. They wanted to know if she had the stomach for it. She did. According to her memoir, by the end of the autopsy, only she and the coroner remained in the room; her colleagues had turned green and bolted for the door.

The last words are Aggie’s. Perplexed by mysteries surrounding Thelma’s death, she wrote in her memoir, “In crucial phases of the case, official versions as told reporters varied from subsequent statements. It was known where and what Miss Todd had eaten on Saturday night. Stomach contents found in the autopsy did not appear to bear out reports on the meal. There were other discrepancies, including interpretations of the condition of the body and its position in the automobile.”

For conspiracy buffs, Aggie talked about a detective she knew who worked to clarify some of the disputed information. She said, “…he was deeper in the mystery, receiving threatening calls…which carried a secret and unlisted number. He was warned to ‘lay off if you know what is good for you.’

“In his investigation, the detective stopped and searched an automobile of a powerful motion picture figure. In the car, surprisingly, was a witness who had reported that Miss Todd had been seen on Sunday. Near the witness was a packed suitcase. The investigator told me the owner of the car attempted to have him ousted from the police department.”

Aggie would not reveal the name of the detective. In summation, she wrote, “There’s a disquieting feeling in working some of these cinema-land death cases, whether natural or mysterious. One senses intangible pressures, as in the Thelma Todd story: After the inquest testimony, in which one sensational theory was that the blonde star, who died of carbon monoxide gas, was the victim of a killer, the case eventually was dropped as one of accidental, though mysterious, death.”

Over the decades, Thelma’s death has been the subject of books, movies, and TV shows; and attributed to everything from suicide to a criminal conspiracy.

I think it best if Aggie and I leave you to make up your own minds about what happened to the beautiful Ice Cream Blonde.

If you are curious, here is CORSAIR, starring Thelma Todd and Chester Morris

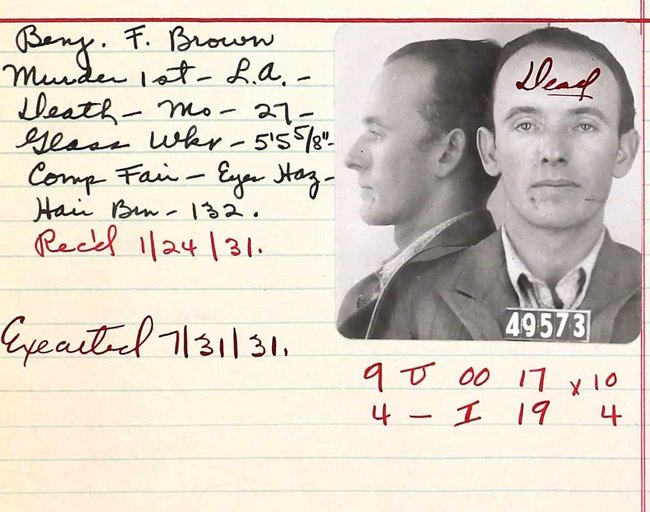

Benjamin confessed to police, but his trial was postponed until January 1931. His attorneys needed time to gather evidence regarding his sanity.

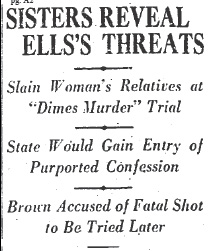

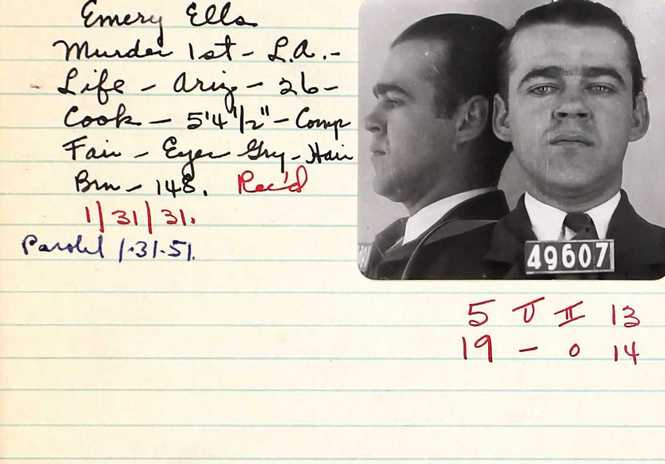

Benjamin confessed to police, but his trial was postponed until January 1931. His attorneys needed time to gather evidence regarding his sanity. Emery’s trial lasted two weeks. On January 8, 1931 after deliberating for just a few hours the jury found him guilty of first degree murder. They recommended life in prison rather than the death penalty asked for by the prosecution. When Emery heard that his life had been spared he turned to his attorney and grinned.

Emery’s trial lasted two weeks. On January 8, 1931 after deliberating for just a few hours the jury found him guilty of first degree murder. They recommended life in prison rather than the death penalty asked for by the prosecution. When Emery heard that his life had been spared he turned to his attorney and grinned.