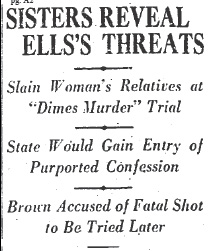

Jury selection in the trial of 41-year-old Santa Monica physician Dr. George Dazey for the 1935 slaying his actress-wife Doris began in early February 1940. Guilty or innocent, George Dazey did one thing right–he hired Jerry Geisler to defend him in court.

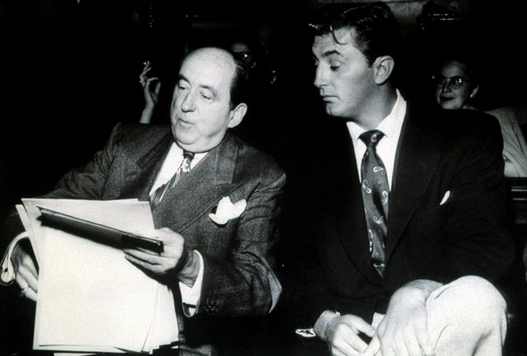

“Get Me Geisler” (pronounced Geese-lar) was a cry that went up routinely in Hollywood circles. Over the course of his half-century of practicing law Geisler defended Errol Flynn, Robert Mitchum, Charlie Chaplin, Lili St. Cyr and many, many others.

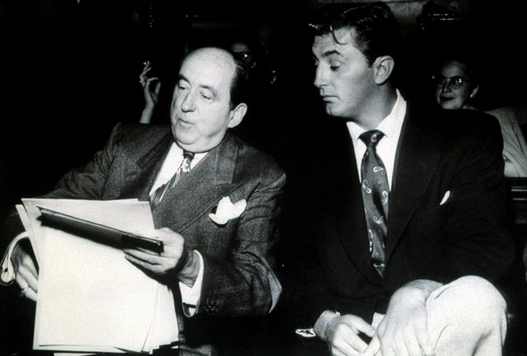

Jerry Geisler w/Robert Mitchum

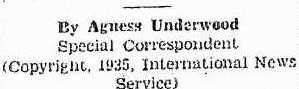

Geisler’s practice wasn’t limited to Hollywood luminaries; he also defended Benjamin “Bugsy” Siegel as well as the odious Dr. George Hodel (for incest). Hodel is well-known for having been a suspect in the 1947 murder of Elizabeth Short, the Black Dahlia.

During the voir dire Deputy District Attorney Hugh McIssac questioned potential jurors on their attitude toward circumstantial evidence and capital punishment. The case against George was entirely circumstantial–which isn’t to say weak; after all, most cases are won on circumstantial evidence. Jerry Geisler’s questions to the possible jurors were very different; he wanted to know:

“If it is brought out here that the deceased might have ended her own life, would you be willing to take that into consideration in the matter of reasonable doubt as applied to this defendant?”

The final jury was composed of three women and nine men. The proceedings hit a snag when on the day after empanelment one of the jurors became too ill to attend the trial. The alternate jurors had not yet been sworn in which led to a legal dispute over when a trial actually begins. Is it when the jury is sworn; when the first witness is called; or when the first witness opens testimony? Opposing counsel agreed to stipulate that the sick juror, Mr. Gieschen, should be discharged and that selection of a jury should continue on the basis of an incomplete panel.

Unconcerned by the minor legal hiccup, Dr. Dazey spent his time working on a crossword puzzle.

George Dazey’s trial opened with a very unusual situation. George Merritt, a major witness in the case, admitted to being a personal friend of both the defendant and Deputy District Attorney McIssac. When Merritt took the stand he testified that Dr. Dazey had called him to the death scene shortly after he claimed to have discovered his wife dead on the garage floor. But his testimony didn’t go as the prosecution had believed it would–Merritt was suddenly unable to recall the doctor making damaging, self-incriminating, statements.

The Deputy D.A. was not pleased:

“Didn’t you tell me at a lunch we had together within recent months that Dr. Dazey kept repeating, ‘Why did I do it? Why did I do it?'”

Merritt said he wasn’t certain.

Peeved with his recalcitrant witness McIssac continued:

“Didn’t you tell me that although Dr. Dazey appeared hysterical and incoherent that you and your friends decided that he was putting on an act?”

Merritt said no.

McIssac told the court that he was taken by surprise. He had every reason to believe that Merritt would testify at the trial the same way in which he’d testified to the grand jury several weeks earlier. At the grand jury hearing he was asked if Dr. Dazey had blurted out, “Why did I do it?” and Merritt had responded: “It might have sound like that.”

Part of the problem faced by the prosecution was that Doris’ death had occurred four years earlier and witnesses are notoriously unreliable even moments after a crime has occurred.

Jerry Giesler made sure to mention that even the police officers who had originally been called out to the scene had to refer to reports they had made at the time of the incident.

After the first day or two of testimony I’d have called the contest between the prosecution and defense a draw. Geisler had made a point about the dim memories of the witnesses, but the prosecution scored a point in refuting the notion that Doris had been suicidal with the testimony of Joe E. Burns, a Frigidaire repairman.

Burns had been called to the Dazey’s home on the day prior to Doris’ death to repair their fridge. He had to return the next day to make further adjustments and he testified that on both occasions Doris seemed to be in a good frame of mind and perfectly lucid when they spoke. That testimony would make it more difficult for Geisler to sell the defense theory that Doris was unstable and suicidal.

Winifred Hart during the silent era.

The most flamboyant of the witnesses to testify was a former neighbor the Dazey’s, Mrs. Wiinifred Westover Hart, the ex-wife of silent film cowboy superstar, William S. Hart.

Winifred was an actress during the silent era, which is how she met her ex-husband. Her first screen appearance was a small role in D.W. Griffith’s 1916 film, Intolerance, but her movie career was over by 1930.

The ex-Mrs. Hart arrived at the murder trial wearing dark glasses and holding a magazine up to shield her face. Her first comment upon taking the witness stand was that she was nervous.

On the night of October 3, 1935 Mrs. Hart said she heard screams coming from the direction of the Dazey home. Deputy District Attorney McIssac asked her:

“Did you tell anyone about hearing these screams after you learned of Mrs. Dazey’s death the next day?”

Mrs. Hart said:

“Oh, I told everybody, I was so upset!”

McIssac asked her if she had received any threats and she answered that she had, but she didn’t recognize the voice over the telephone. There was no way to corroborate her testimony about the threatening calls and on top of that it was difficult for the jury to take her seriously because she was so theatrical. According to the L.A. Times the former silent film actress had a flair for the histrionic.

When it was Jerry Geisler’s turn to question Mrs. Hart he opened with:

“Now don’t get nervous at me.”

Mrs. Hart went on to testify that in the late afternoon of October 3, 1935 she and her mother, Mrs. Sophie Westover, had been listening to the radio when they heard screaming and crying. Hart testified:

“It sounded like a boy being teased—boys used to play in a vacant lot next to us–and after a while I got up and shut the window and turned up the radio.”

Hart knew what time they heard the ruckus because she and her mom were listening to a scheduled program featuring Rudy Vallee.

Winifred Hart c. 1940s

Another witness, Douglas O’Neal, 17, lived near the Dazey’s home and he testified that had seen Dr. Dazey’s car parked by the Dazey residence hours before the doctor said he’d arrived home to find his wife dead.

Jerry Geisler established that the boy couldn’t be certain it was Dr. Dazey’s car because he hadn’t seen the license plate numbers and the car was a popular make and model.

Mildred Guard, sister of the dead woman, testified that she’d visited her sister many times while she was married to Dr. Dazey. She recalled one occasion, a short time prior to the birth of the couple’s child, when there was some rather disturbing breakfast table conversation:

“George [Dr. Dazey] was talking and he said, ‘If the baby looks like_____’ and here he mentioned the name of a certain man–I’ll kill both Doris and the baby.”

Prosecutor McIassac asked Mildred how Doris had replied. Mildred said that her sister had admonished George, asking him not to talk like that.

The mystery man was referred to in court only by his first name, which was Carl. During questioning by Jerry Gisler, Mildred testified that she knew that her sister had been going out with Carl up to the time she began dating Dr. Dazey. When asked if Doris had quit seeing Carl after starting a relationship with George, Mildred admitted that she had no idea.

Geisler said:

“Well, you know the baby didn’t look anything like Carl?”

To which Mildred replied that the baby didn’t bear the slightest resemblance to Carl. Mildred’s testimony concluded with her description of an incident that had occurred on a night when she was staying at the Dazey home. She said she heard Doris scream then call out her name:

“I went to her room and she was partly sitting up in bed and had a frightened look on her face. The doctor was standing about three feet from the bed, fully dressed and apparently sober. He looked very mean. His hands were clenched, his face was purple and he was grating his teeth. She had a look of terror on her face.”

Dr. Dazey allegedly told Mildred he was “only fooling” and asked her to leave the room. Doris never explained the incident to Mildred.

As George Dazey’s trial entered its second week the prosecutors offered their version of Doris’ death–they contended that the doctor had incapacitated his wife in some way then carried her body into their garage and placed her head near the car’s exhaust pipe. In fact Doris’ face was so near to the exhaust pipes that she received burns which the prosecution declared would have been highly improbably if she had committed suicide as had been suggested by George’s defense team.

Unidentified women queued up to watch the trial of Dr. George Dazey.

Everyone who came to the courtroom on February 13, 1940 was there to hear the testimony of Dr. Dazey’s former nurse, and occasional “social companion”, Miss Frances Hansbury. Frances had testified at the grand jury hearing that George had confessed to her that he had murdered Doris.

If the jury believed Frances it could be all over for George Dazey–he might dance into eternity at the end of a hangman’s noose.

NEXT TIME: The trial and verdict.

Here in L.A. there was the murder trial of O.J. Simpson, the so-called Trial of the Century. If you remove fame, wealth, and race and reduce the crime to its basic elements you end up with nothing more than a tragic domestic homicide–the type of crime which is altogether too common everywhere–yet the case continues to fascinate.

Here in L.A. there was the murder trial of O.J. Simpson, the so-called Trial of the Century. If you remove fame, wealth, and race and reduce the crime to its basic elements you end up with nothing more than a tragic domestic homicide–the type of crime which is altogether too common everywhere–yet the case continues to fascinate.

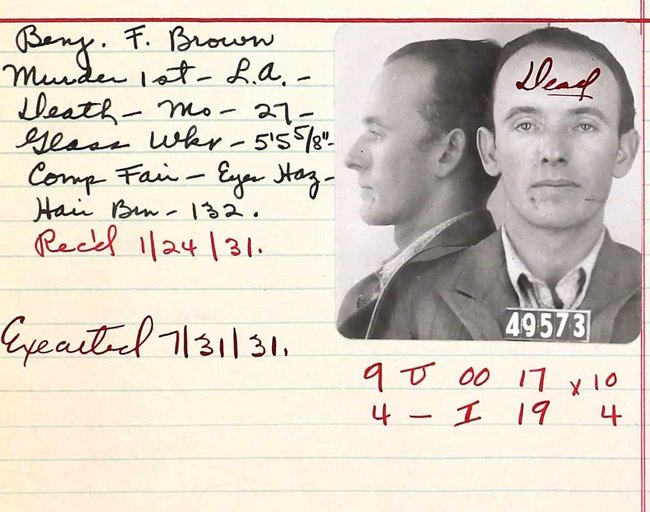

Benjamin confessed to police, but his trial was postponed until January 1931. His attorneys needed time to gather evidence regarding his sanity.

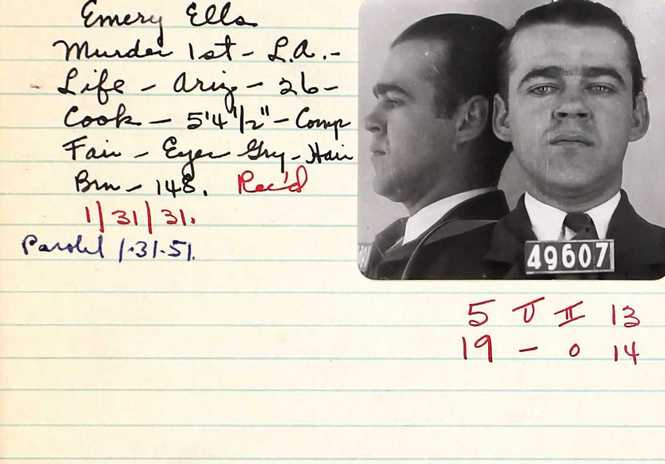

Benjamin confessed to police, but his trial was postponed until January 1931. His attorneys needed time to gather evidence regarding his sanity. Emery’s trial lasted two weeks. On January 8, 1931 after deliberating for just a few hours the jury found him guilty of first degree murder. They recommended life in prison rather than the death penalty asked for by the prosecution. When Emery heard that his life had been spared he turned to his attorney and grinned.

Emery’s trial lasted two weeks. On January 8, 1931 after deliberating for just a few hours the jury found him guilty of first degree murder. They recommended life in prison rather than the death penalty asked for by the prosecution. When Emery heard that his life had been spared he turned to his attorney and grinned.

![Convicted murderer, Russell Beitzel getting a shave in prison as other inmates look on, Los Angeles, Calif., 1928. [Photo courtesy of UCLA Digital Collection]](https://derangedlacrimes.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/03/beitzel-shaved_ucla.jpg)