Happy New Year!

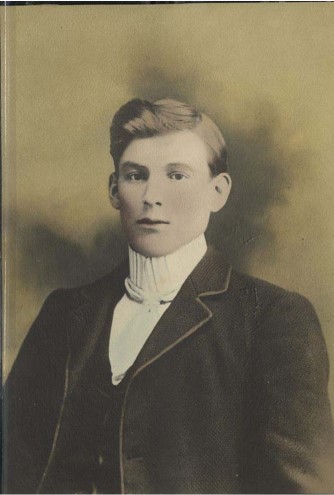

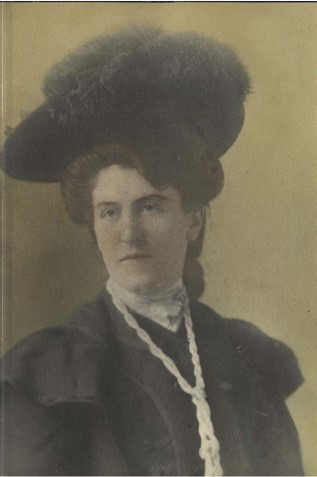

Ohio native Grace Hunt was 17 when she married 41-year-old Charles Price Grogan in Los Angeles on April 5, 1902. It was an advantageous marriage for both. Charles basked in the glory of his triumphs, with the press dubbing him the “Olive King,” and a radiant Grace by his side, a queen befitting his grandeur. A few days prior to their fifth wedding anniversary, they welcomed a son, whom they named Charles Patrick Grogan.

Grace and Charles were married for over a decade before they separated. The difference in their ages may have sunk the marriage. Whatever their reasons, the couple had separated by the late 1910s and divorced by the 1920 census—at least that was how Charles declared his marital status. Grace, for the same census, gave her marital status as a widow. Why the discrepancy? Simple; divorce stigmatized women.

Grace was luckier than many women because California, at least in its laws, was more tolerant of divorce than other states. The State’s first divorce law in 1851 recognized impotence, adultery, extreme cruelty, desertion or neglect, habitual intemperance, fraud, and conviction of a felony as legitimate grounds for divorce.

Despite the law’s progressive attitude, divorce could ruin a woman, which is why many women found it easier to claim widowhood than risk suffering the loss of status if their divorce became public knowledge. It seems absurd to us now in these days of no-fault divorce and “conscious uncoupling” (a phrase coined in 2014 by celebrity Gwenyth Paltrow to describe her separation from her musician husband, Chris Martin), but divorce was not a simple matter when Grace and Charles called it quits.

The couple’s family and intimate friends would have known the truth, and the rest of local society may have acknowledged Grace’s widowhood with a nod and a wink and allowed her to continue her fiction unchallenged.

Grace’s claim to widowhood would edge closer to the truth when Charles died of apoplexy (internal bleeding—perhaps because of a stroke) on July 8, 1921.

The Olive King was a wealthy man who loved his only son. He bequeathed Patrick his entire fortune, estimated to be between $1 and $2 million dollars. Until he turned 25, Grace was to administer Patrick’s monthly allowance, which amounted to a princely sum of $800 per month. An agreement had been reached by Grace and Charles regarding their divorce. The couple agreed Charles would create a trust fund, not to exceed $50,000, for her maintenance. To put things into perspective, $50,000 in 1921 is equivalent to three quarters of a million dollars today. And Patrick’s monthly allowance is equivalent to about $12,000. A fortune like the one Charles left Patrick and Grace can attract the best people in society—it can also be a magnet for the worst of humanity.

In her 30s, Grace was beautiful, wealthy, and prominent. She would make a wonderful wife for the right man.

NEXT TIME: Grace meets a new man, as The Murder Complex continues.

I first encountered Agness “Aggie” Underwood while researching crime in Los Angeles. Aggie’s name appeared many times in various accounts, which piqued my curiosity. I had to know more about one of the few women reporters working in the field during the 1930s and 1940s.

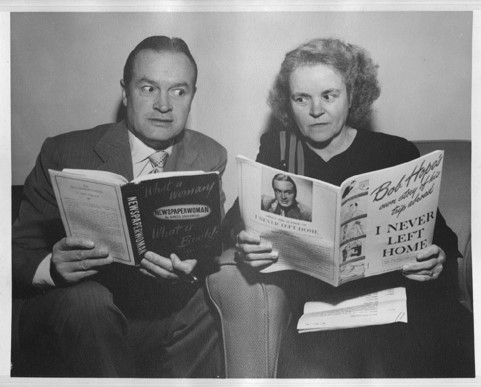

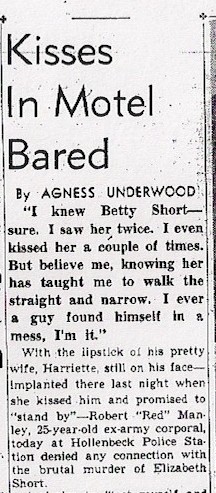

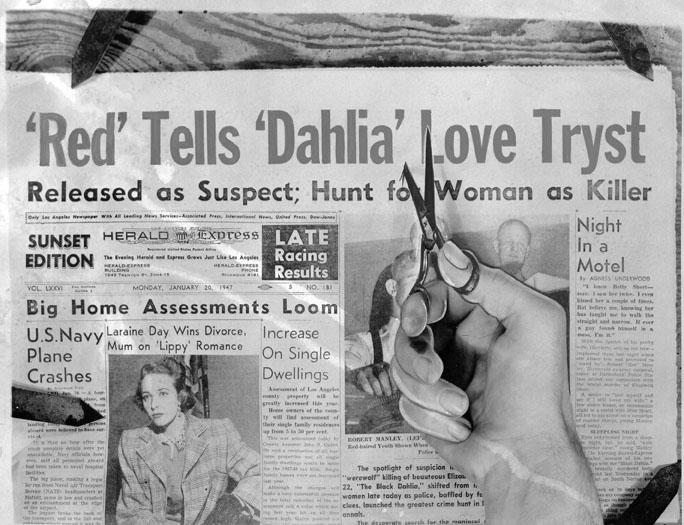

Aggie’s 1949 autobiography, NEWSPAPERWOMAN, was a revelation. Here was a woman who reported on the major crime stories of her day, including the 1947 murder of Elizabeth Short, the Black Dahlia.

Agness May Wilson was born to Clifford and Mamie Sullivan Wilson in San Francisco in 1902.

Her sister, Leona, followed four years later. By 1904, the family had moved to Belleville, Illinois, and it was there Mamie, 25 years old, died of rheumatism of the heart. Before she died, she had Aggie promise to care for Leona. That is a heavy burden to place on the shoulders of a little girl.

Aggie’s father, Clifford, was a glassblower who traveled for work. After Mamie’s death, he passed Aggie and Leona to relatives. Eventually, relatives placed them in separate foster homes. Aggie fought to keep Leona with her, but her best efforts were no match for the adults who tore them apart. The sisters lost touch.

Aggie’s life in the foster home was hard. She struck out on her own in her early teens. Eventually landing in Los Angeles, she worked at the Pig ‘n Whistle downtown. Things looked up when Harry Underwood, a soda jerk at the Pig, proposed to her when a greedy relative threatened to report her for working underage—unless she turned over her entire paycheck. Aggie gratefully accepted Harry’s timely proposal.

We characterize the 1920s as a free-wheeling time when liquor and money flowed. It didn’t hold true for everyone. The Underwoods, like many other families, struggled financially. By 1924, they had two children, Mary Evelyn, and George Harry. They realized they could not make it in Los Angeles, so they traveled out-of-state, seeking new opportunities. During their travels, Aggie located Leona, and they reunited.

The Underwoods returned to Los Angeles, and Leona moved in to the family’s home on the city’s east side. Even with Harry and Leona working day jobs, money was tight. At least Aggie had achieved her dream of having a family. What more could she ask for? How about a pair of stockings?

By October 1926, Aggie grew tired of wearing Leona’s hand-me-down stockings. She went to Harry and asked for the money to buy a pair of her own. He told her they couldn’t afford them.

Incensed, Aggie said if he wouldn’t buy them for her, she’d get a job and buy them herself. It was an empty threat. She hadn’t worked outside the home in several years. What could she do to earn a living?

Before she could turn to the want ads, Evelyn Conners called. She and Aggie had remained close since meeting at the Salvation Army Home several years earlier. Evelyn worked at the Los Angeles Record and got Aggie a temporary job at the switchboard. Evelyn knew Aggie was qualified because they once worked together at the telephone company.

Aggie enjoyed being at the Record, and she hoped to stay through the New Year. She got lucky. Gertrude Price was the women’s editor and wrote an advice column under the name Cynthia Grey. Each year, Gertrude organized a food drive for the city’s poor, and she needed help to fill and deliver the baskets. She asked Aggie if she would stay and help. Without hesitation, Aggie accepted; it meant seven or eight more weeks of steady work.

Aggie assumed she would return to her housewifely chores at in January 1927, but Gertrude had other plans.

Her conscientiousness had not gone unnoticed or unappreciated. Gertrude offered Aggie a part-time job as her assistant. It didn’t pay as well as the switchboard, only five dollars per week. Once she did the arithmetic, Aggie realized she wouldn’t net a dime after she paid a babysitter to watch her kids. Why did she stay if she wasn’t making any money? Aggie didn’t know it yet, but she was in love with the newspaper business.

Throughout 1927, Aggie tackled each task that Gertrude handed her with enthusiasm. In return, Gertrude became her mentor and confidante.

By the time the 1928 holiday season rolled around, Aggie was a fixture at the Record. She again assisted Gertrude Price with the Christmas baskets program. The Underwoods’ financial woes were far from over; but if their holiday was lean, so be it. She felt fortunate to be surrounded by her family.

Ironically, even though Aggie cherished family life, she revealed few details about hers in her autobiography. In fact, she never mentions Harry by name, only referring to her unnamed husband. The reason is simple, she and Harry were divorced a few years before the publication of NEWSPAPERWOMAN. Aggie chose to highlight her professional achievements.

Aggie’s omissions make sense when you consider her position at the time. She was still only a couple of years into her city editorship at the Herald. Personal details might negatively impact her career. I think perhaps the most important thing for Aggie was he desire never to be a “sob sister.” She didn’t want to tug at people’s heartstrings in the copy she wrote for the paper, and especially not in her autobiography. That said, I really wish she had made good on her plan to author a more complete autobiography in her retirement. She never got around to it.

It is no surprise she never wrote about an event that must have devastated her—the death of her sister, Leona, on December 6, 1928. Without Aggie’s input,, we can only speculate on what happened, and what impact it had on her.

Like most families, the Underwoods had a work week routine. December 6 was a Thursday, so Leona dropped her niece and nephew off at the babysitter, as she usually did. While the rest of the family was out for the day, Leona consumed ant paste.

The principal ingredient is arsenic. Ant paste was a common poison found in most households. At twenty-two years old, Leona may have believed that taking poison would be a quick and easy death. She could not have been more wrong. Death by arsenic poisoning is excruciating. Depending on the dose, it can take hours or even days to kill.

Aggie’s established routine was to swing by the babysitter after work, pick up the children, and then go home. When Aggie arrived home, she found Leona. I cannot imagine how Aggie felt. Records show they transported Leona to Pohl Hospital on Washington Boulevard. They admitted her at 3:25 p.m. By 4:00 p.m. her body was in the county morgue. Why did Leona take her life? Her death certificate gives two reasons: “Love affair & financial difficulties.”

Leona’s death notice appeared in the Los Angeles Times the next day. The brief notice said they would hold funeral services on Saturday, December 8, 1928, in the chapel of Ivy H. Overholtser on South Flower Street.

Without input from Aggie, it is difficult to calculate the impact that Leona’s death had on her, but it must have been enormous. Did she feel guilty about failing to honor her mother’s dying wish for a second time? As tragic as Leona’s death was, with two children and a husband to care for, Aggie had no choice but to turn her attention toward the living.

NOTE: The holidays are not a joyous time for everyone. If you or someone you care about is in a crisis, please call 988 Suicide and Crisis Lifeline, or call the Suicide Prevention Lifeline at (800) 273-8255 to talk with a caring, trained counselor. It is free, confidential, and available 24/7.

Welcome to Deranged L.A. Crimes. Ten years ago, I started this blog to cover historic Los Angeles crimes. I am not surprised that I haven’t even scratched the surface of murder and mayhem in the City of Angels.

I have been absent from the blog for a while, focusing on finishing my book on L.A. crimes during the Prohibition Era for University Press Kentucky. It’s not done yet, but I’m close. No matter, it is time to return to the blog. It is something I love to do.

Focusing my energy on the book, I failed to pay tribute to the inspiration for Deranged L.A. Crimes, Agness “Aggie” Underwood, on December 17, 2022, the 120th anniversary of her birth. If you aren’t familiar with Aggie, I’ve written about her many times in previous posts.

In 2016, I curated a photo exhibit at the Los Angeles Central Library downtown. The exhibit, for the non-profit Photo Friends, featured pictures from cases and events Aggie wrote about over the course of her career. I wrote a companion book, The First with the Latest!: Aggie Underwood, the Los Angeles Herald, and the Sordid Crimes of a City.

Aggie is a dame worth learning about. She is a legendary crime reporter, who worked in the business from 1927 until her retirement from the Los Angeles Herald in 1968. A force to be reckoned with, Aggie worked as a reporter until her promotion to City Editor of the Herald in January 1947, while covering the Black Dahlia case. She was the only Los Angeles reporter, male or female, to get a by-line for her reporting on the ongoing investigation.

On her retirement, she told a colleague that she feared being forgotten. That won’t happen on my watch. Thanks again, Aggie, for the inspiration. Deranged L.A. Crimes is dedicated to you.

Among the things I’ve learned over the years researching and writing about crime, is that people don’t change. The motives for crime are timeless: greed, lust, anger, betrayal, and jealousy are but a few.

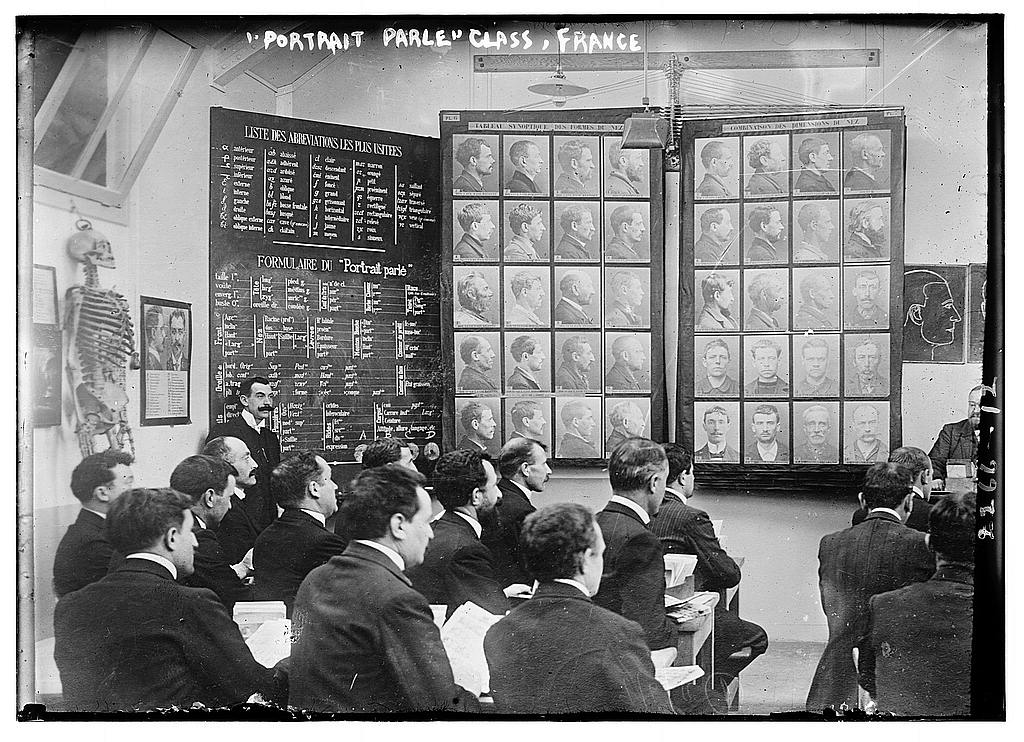

What is different is crime detection. Science has come a long way. Detectives no longer use the Bertillon system to identify criminals—they use DNA. I think part of the reason I’m drawn to historic crime is the challenges overcome by former detectives and scientists. Despite the advancements in science, it is my belief that if it was possible to pluck the best detectives and scientists from the past and set them down in the present, they would still be great. I am amazed at the cases they solved.

I look forward to this new year, and to the challenges it will bring. I am so glad you are here, and I invite you to reach out if you have questions and/or suggestions.

Best to all of you in the New Year.

Joan

Being a researcher is like being an explorer without a map. I set sail and go where the tides take me. It is one reason I love what I do.

On Thursday, I was at the Hall of Justice where I volunteer for the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department Museum. My current project is transcribing a 1895-1896 L.A. County Jail Register and entering the information into a searchable file. The register is a fascinating glimpse into the city and some of its more colorful, and criminal, inhabitants.

Besides entering the details of an arrest: date, suspect name, police officer’s name, type of crime, etc., I document cases when I can find information. There weren’t many murders, but there were plenty of other crimes which merited column space in the local newspapers.

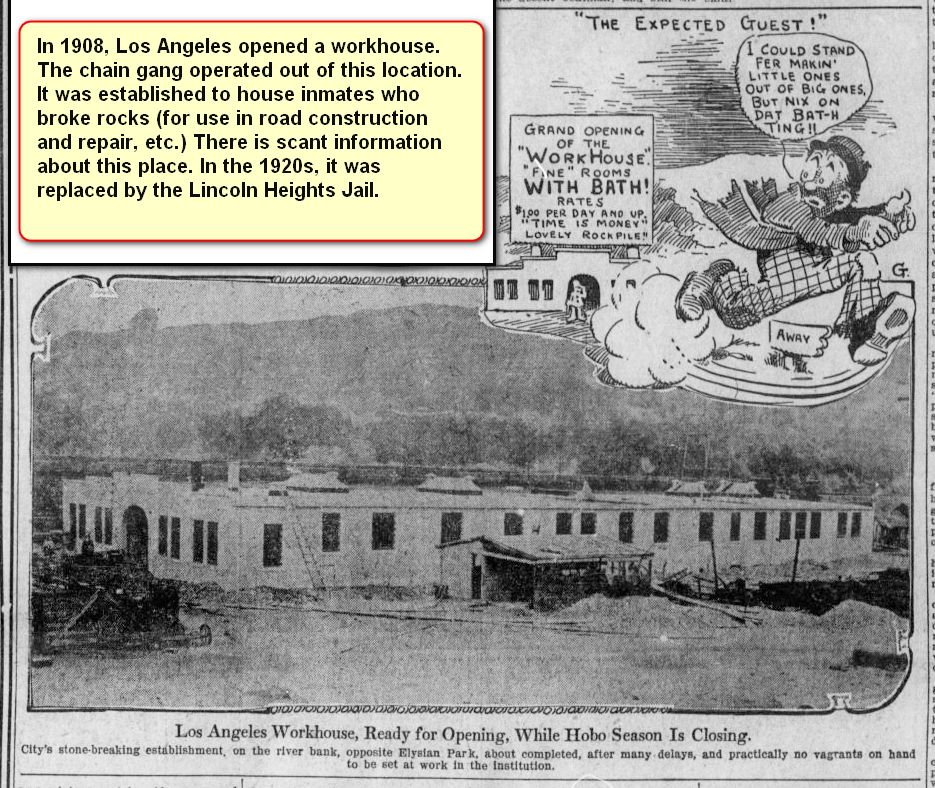

I followed one miscreant right to the door of the Los Angeles County Workhouse about which, I confess, I knew nothing. I dug deeper and found photos of the interior and exterior of the building. Also, a photo and the name of the man in charge, Lt. Charles Dixon.

They officially designated the facility LAPD substation No. 2. Its territory comprised all of Boyle Heights and the entire northern district of the city.

Rumor had it that Lt. Dixon’s assignment was politically motivated. It was, some said, an exile not an opportunity. If Dixon played politics and lost, whose toes did he step on? Chief of Police Edward Kern assigned Dixon to the workhouse; so maybe Dixon crossed Kern and paid for it with a post in the boondocks.

I will dig further into the politics of the era but, meanwhile, I found Chief Kern to be an interesting character in his own right.

Kern’s background was as a teamster and as the chief of supplies for the U.S. Army’s campaign against Geronimo. Like many other former soldiers, Kern landed in Los Angeles.

In 1902, constituents elected him to represent the 7th district on the City Council. Reelected in 1904, he resigned after being appointed police chief–even though it appears he had no law enforcement experience.

In January 1909, Kern continued his public service as an appointee to the Board of Public Works. He lasted two months. Complaints that he was unqualified dogged him, and rather than be removed he quit in March of that year.

Kern battled personal demons and “was given to periodical drunken sprees.” In 1911, he admitted himself to the State Hospital for Inebriates in Patton, California on the advice of his physician, Dr. Sumner J. Quint. Quint became Kern’s legal guardian.

He was unwell when discharged from the hospital. The Los Angeles Times described him as “pitiful” and said “His face was unshaven, haggard and drawn.”

In 1912, Kern went to El Paso, Texas, ostensibly on business. On April 20th, a chambermaid found his body in the bathtub of the hotel where he was staying. He died of a self-inflicted gunshot wound to the head. He left no note, but his revolver, a gift from friends in Los Angeles, lay beside his body.

NOTE: Writing this post, I am reminded of an early TV show, THE NAKED CITY, a police procedural set in New York. It always ended with the narrator saying, “”There are eight million stories in the naked city. This has been one of them.”

The population of Los Angeles in 1895 was approximately 75,000. The above story has been one of them.

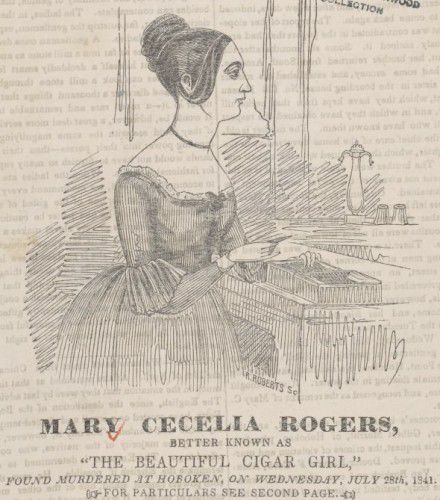

MARY CECILIA ROGERS

Edgar Allan Poe’s The Mystery of Marie Roget, is cited as the first murder mystery based on details of an actual crime. I am skeptical of firsts, but if Poe’s story is not the first, it is an early entry. It appeared in Snowden’s Ladies’ Companion in three installments, November and December 1842 and February 1843.

Behind Poe’s tale of Marie Roget is the murder of Mary Cecilia Rogers.

Rogers, a tobacco shop employee, became known as the Beautiful Cigar Girl. She disappears on October 4, 1848, and local papers report her elopement with a naval officer. She returns later, sans husband.

She disappears again on July 25, 1841. Friends see her at the corner of Theatre Alley, where she meets a man. They walk off together toward Barclay Street, ostensibly for an excursion to Hoboken.

Three days later, H.G. Luther and two other men in a sailboat pass by Sybil’s Cave near Castle Point, Hoboken. Floating in the water they see the body of a young woman. They drag it to shore and contact police.

According to the New York Tribune, Rogers is “horribly outraged and murdered”. Questions regarding Rogers’ death remain. It is alleged she ended up in the river following a failed abortion. The scenario is credible, in part, because her boyfriend committed suicide and left a note suggesting his involvement in her death.

GRACE BROWN

I love it when a novel is based on a true crime. One of my favorites is An American Tragedy by Theodore Dreiser. Dreiser draws inspiration from a murder in the Adirondacks.

In 1905, Chester Gillette takes a job as a manager in an uncle’s skirt factory in Cortland, New York. It is there he meets factory worker, Grace Brown. They begin an affair and she becomes pregnant.

Chester is neither interested in being a husband, nor in being a father. He takes Grace on a trip to the Adirondack Mountains in upstate New York. Using the alias, Carl Graham, Chester rents a hotel room, and a rowboat.

Grace believes the hotel is where they will spend their honeymoon following a visit to the local justice of the peace. In anticipation of her new life with Chester, Grace packs all of her belongings in a single suitcase.

Chester’s suitcase is small. He is not beginning a life with Grace.

On July 11, the couple takes a rowboat out into the middle of Big Moose Lake. There is no marriage proposal. No wedding ring. He beats her over the head with his tennis racquet and pushes her overboard to drown.

On July 13, 1906, The Sun reports the tragic drowning of a couple in Big Moose Lake. Grace’s body floats to the surface the next day. The body of her companion, Carl Graham, is missing.

Fearing he is dead, police search for Carl. They soon learn the true identity of Grace’s companion. He is alive, well, and his name is not Carl. Police arrest Chester. He denies responsibility for Grace’s death. He insists she committed suicide. The bad news for Chester is none of the physical evidence supports his version of events.

The jury shows no mercy—they find him guilty and sentence him to death.

On March 30, 1908, they execute Chester in the electric chair at Auburn Prison in Auburn, New York.

LOIS WADE

March 4, 1932.

Soaked to the skin, bleeding from the head, and covered in bruises, seventeen-year-old Lois Wade stumbles into the road near Mountain Meadows Country Club in Pomona. A Good Samaritan takes her to Pomona Valley Hospital.

The hospital calls the Sheriff’s department, and deputies arrive to take Lois’ statement. She tells them a terrifying story.

She is is walking from downtown Pomona to her parent’s home at 349 East Pasadena Avenue, when a stranger pulls up alongside her and offers her a ride. She accepts, but rather than taking her home, the man stops his car on Walnut Avenue near an abandoned well and beats her.

Lois’ attacker forces her into the well and shoves her down witht a pole when she attempts to climb out. When Lois vanishes from his view, the man gets in his car and drives away.

The motiveless attack makes little sense, and deputies question Lois’ account. The next day, she revises her story.

Her attacker is not a stranger as she originally claims; he is her nineteen-year-old married lover, Frank Newland.

Deputies Killion and Lynch arrest Frank at his home at 918 South San Antonio Street, Pomona. They book him on a charge of assault with intent to commit murder. Frank denies the attack.

As Lois lay in serious condition in the hospital, the D.A. revises charges against him to include statutory rape. Because of the severity of Lois’ wounds and her inability to appear in court, Judge White resumes Frank’s hearing at Lois’ hospital bedside.

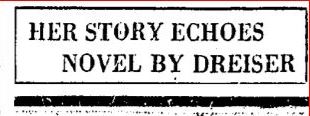

Within a month of the attempt on Lois’ life, Frank goes to trial. Local newspapers pick up on the similarities between Frank and Lois and the characters in Theodore Dreiser’s An American Tragedy.

Future Los Angeles mayor, Fletcher Bowron, sits on the bench. Public interest in the trial is high and draws an enormous crowd—the largest since the 1929 rape trial of theater mogul Alexander Pantages.

The trial begins on April 28; Lois takes the stand, and the courtroom hangs on her every word.

Lois is low-key and demure as she testifies to her ordeal.

“By prearrangement we met on a corner in Pomona. We went in his roadster to the Mountain Meadows Country Club, where he drove off the road and stopped the car. We sat in the car for a half-hour; yes, we kissed and loved. He then suggested that we walk over to an old windmill and abandoned well nearby.”

“We looked in the well and then suddenly he turned around and struck me over the head with a club. I fell to the ground. He struck me eight or ten times more and kicked me several times.”

Frank grabs Lois by the feet and drags her, struggling and screaming ten feet to the well. No match for Frank, he overpowers her and throws her in the well.

Lois lands in twenty-five-feet of water. She bobs to the top, and fights for her life. Frank uses a railroad tie to shove Lois under water. A photo of Deputy W.L. Killon, puts the size of the weapon into perspective.

Convinced Lois is dead, Frank gets into his car and drives away.

Lois claws herself up the wall of the well. She crawls over the edge, tumbles onto the ground, then rises and lurches into the street to summon help. A man stops his car to render aid. Amazingly, Lois’ Good Samaritan is a doctor.

Dr. Roy E. St. Clair testifies to finding Lois in the road.

“I was driving to Pomona on the Mountain Meadows Road about 8:30 p.m. last March 4 when I heard a cry and the lights on my car picked up the figure of Miss Wade standing with her right arm out-stretched. I backed up my machine, and she came to the door and said ‘Take me to a doctor.’”

NEXT TIME: A strange ending.

Ten days ago I narrated the first part of the Dear Hattie post. Your feedback was encouraging, and I took your constructive comments to heart. I will get better as I go along. I truly believe that an audio version of Deranged posts is an idea whose time has come.

I have other ideas for content, too. In my research I often find newspaper and magazine stories that run the gamut — some are heartwarming, others sleazy or just flat-out horrifying, but I don’t feel they are enough to support a full written post. These gems are perfect to share via audio.

I’ll begin digging through my files to see what I can unearth.

Meanwhile, here is the conclusion of Dear Hattie.

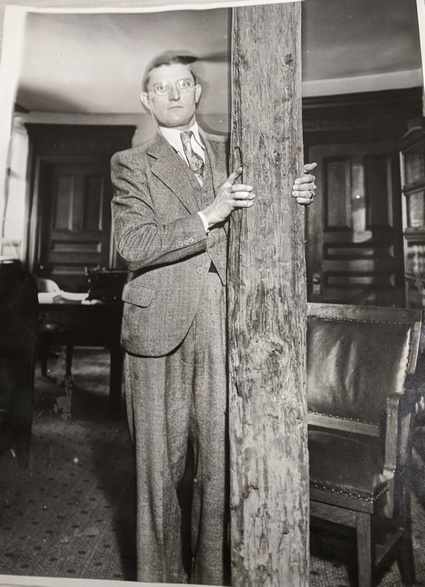

Yesterday was the 117th anniversary of Aggie Underwood’s birth. In her honor the Central Library downtown is hosting a party on Saturday, December 21, 2019 at 2 pm.

I will speak about Aggie and her many accomplishments from her time as a switchboard operator at the Record to her groundbreaking promotion to city editor at the Evening Herald and Express. And yes, there will be cake.

Aggie inspired me to create this blog and her Wikipedia page on December 12, 2012. Aggie loved the newspaper business as much as I love writing for the blog and connecting with all of you.

Deranged L.A. Crime readers are an impressive group. They include current and former law enforcement professionals, crime geeks (like me), and the victims of violent crime. I have even been contacted by a serial rapist (a despicable scumbag).

Each December I reflect on the year that is ending and make plans for Deranged L.A. Crimes. In 2020, the blog’s reach will extend to encompass all of Southern California, which includes the following counties: Los Angeles, San Diego, Orange, Riverside, San Bernardino, Kern, Ventura, Santa Barbara, San Luis Obispo, and Imperial.

I look forward to new stories, personalities and challenges.

Please join me as we enter the Roaring Twenties. This time, no Prohibition.

Aggie hoists a brew c. 1920s. [Photo courtesy LAPL]

Aggie Underwood was born on December 17, 1902 and Deranged L.A. Crimes was born on December 17, 2012, so there’s a lot to celebrate today. We have so many candles on our birthday cake it will take a gale force wind to blow them all out.

It was Aggie’s career as a Los Angeles journalist that inspired me to begin this blog; and my admiration for Aggie and her accomplishments has grown in the years since I first became aware of her.

Aggie at a crime scene in 1946.

Aggie’s newspaper career began on a whim. In late 1926, she was tired of wearing her sister’s hand-me-down silk stockings and desperately want a pair of her own. When she asked her husband Harry for the money, he demurred. He said he was sorry, they simply couldn’t afford them. Aggie got huffy and said she’d buy them herself. It was an empty threat–until a close friend called out of the blue the day following the argument and asked Aggie if she would be interested in a temporary job at the Daily Record. Aggie never intended to work outside her home, but this was an opportunity she couldn’t pass up.

In her 1949 autobiography, Newspaperwoman, Aggie described her first impression of the Record’s newsroom as a “weird wonderland”. She was initially intimidated by the men in shirtsleeves shouting, cursing and banging away on typewriters, but it didn’t take long before intimidation became admiration. She fell in love with the newspaper business. At the end of her first year at her temporary job she realized that she wanted to be a reporter. From that moment on Aggie pursued her goal with passion and commitment.

Aggie at her desk after becoming City Editor at the Evening Herald & Express. Note the baseball bat — she used it to shoo away pesky Hollywood press agents. [Photo courtesy LAPL]

During a time when most female journalists were assigned to report on women’s club activities and fashion trends, Aggie covered the most important crime stories of the day. She attended actress Thelma Todd’s autopsy in December 1935 and was the only Los Angeles reporter to score a byline in the Black Dahlia case in January 1947. Aggie’s career may have started on a whim, but it lasted over 40 years.

Look closely and you can see Aggie’s byline under “Night In a Motel”. [Photo courtesy LAPL]

Over the past nine years I’ve corresponded with many of you and I’ve been fortunate enough to meet some of you in person. Your support and encouragement mean a lot to me, and whether you are new to the blog or have been following Deranged L.A. Crimes from the beginning I want to thank you sincerely for your readership.

There will be many more stories in 2022, and a few appearances too. Look for me in shows on the Investigation Discovery Network (I’ve been interviewed for Deadly Women, Deadly Affairs, Evil Twins, Evil Kin and many others.) I am currently appearing in the series CITY OF ANGELS: CITY OF DEATH on HULU.

Kentucky University Press will publish my compilation of tales on L.A. crime during Prohibition. Title is TBA.

You can find my short story in the recently released anthology, PARTNERS IN CRIME, edited by Mitzi Szereto.

Whether it is on television, in the blog or some other medium I’m looking forward to telling more crime tales in 2022.

Happy Holidays and stay safe!

Joan

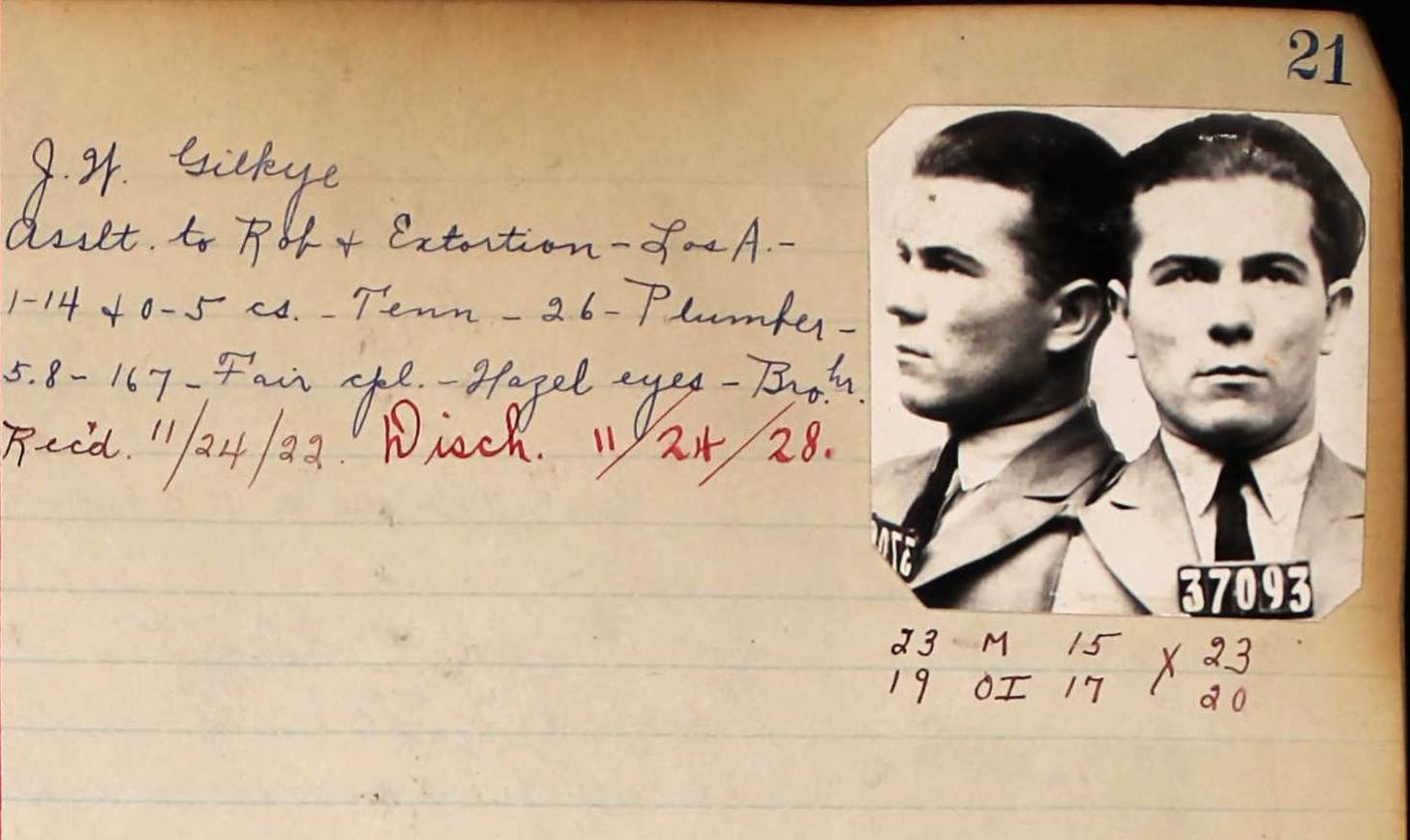

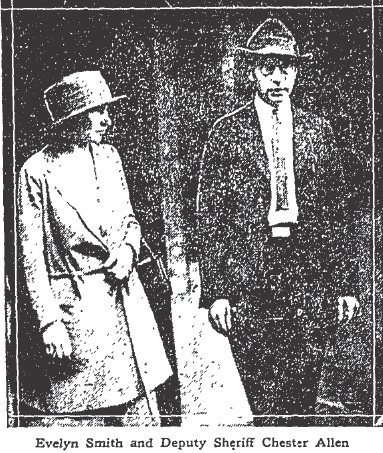

Not long after the bloody shootout between the Burton gang and Sheriff’s deputies at the Union Ice Company, in which all of the bandits except J.W. Gilkye were killed, deputies found Edward Burton’s girlfriend. Investigators located the young woman in a room at the Superior Hotel. She was taken into custody under her alias, Mary Dayke, but quickly revealed her given name, Evelyn Smith.

Smith, like Burton, was from Chicago. Questioned by Chief of Criminal Investigation, A.L. Manning and Deputy Sheriff Chester Allen, Smith said that she had no idea what Burton was up to or why he had left Chicago for Los Angeles. “I know nothing of Burton’s crimes. I did not realize he was leading a life of crime until he was arrested in the raid. Even then I did not believe he was the man who shot the motor officer.

Smith continued: “I came out from Chicago last May to join Burton. Be he soon lost interest in me. He told me I was not the kind of a girl to stick with him. Last Tuesday afternoon, only a few hours before he was killed, he accused me of being too inquisitive. He said I asked too many questions, told me to mind my own business. And then he beat me severely.”

Sheriff’s investigators asked Smith about the two one-way train tickets to Chicago that were found in Burton’s coat pocket, but again she claimed to know nothing. Evidently, Burton had a new woman in his life; a blonde with bobbed hair who had accompanied the bandit gang on a number of robberies. Smith said Burton planned to “ditch” her for his new squeeze and leave Smith in Los Angeles to fend for herself.

Sheriff’s deputies conducted raids at several locations in an attempt to round up other members of the gang. The lawmen came up empty. The gunsels, aware that the deputies wielded sawed-off shotguns and were prepared to do battle, had fled the city for parts east.

Only J.W. Gilkye, the lone bandit to survive, was left to answer for the crimes he and his fellow thugs had perpetrated. Gilkye survived only because he had dropped his weapon and refused to fight when deputies drew down on him at the ice company.

During questioning, Gilkye said: “You got enough on me without me telling you more.” And then he proceeded to tell Chief Deputy Manning a lot more. Like many crooks Gilkye loved the sound of his own voice and couldn’t resist crowing about his criminal accomplishments and playing the tough guy. “I may get hooked for a long time up the road, but I ain’t through yet. We were double-crossed, we were, by one of our own gang. But I’ll get him if it takes all my life. He double-crossed us and caused three of my best pals to get killed. But they were nervy–had the goods.” The “goods” can’t do much for you when you’re dead.

Gilkye wasn’t as nervy as his pals had been, so he lived to tell the tale. He was tried and convicted for his part in the ice company job, but before he left Los Angeles County Jail for San Quentin, he nearly made good on his promise to get even with the man who had dropped a dime on the gang.

The snitch was Roy Melendez. Melendez and Gilkye encountered each other in the County Jail where, according to witnesses, Gilkye “roared like an infuriated animal” when Melendez was placed in lock-up. Gilkye would have murdered Melendez with his bare hands if jail attendants hadn’t intervened.

Melendez may have met a bad end even though Gilkye wasn’t able to lay another finger on him. When Melendez failed to appear in court on a bum check charge an unnamed official opined: “Either Melendez has been killed or they have made it so hot for him he is afraid to show up.” A bench warrant was issued for Melendez, but he was nowhere to be found.

Members of the Sheriff’s Department breathed a sigh of relief. The Burton gang’s brief reign in Los Angeles was over.

* * *

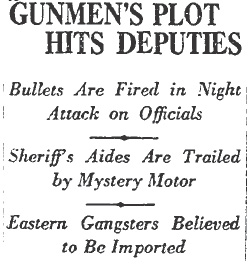

Late in February 1923, two men from Chicago arrived in Los Angeles. The men weren’t tourists, they were on a mission to assassinate the deputies they held responsible for killing Edward Burton and two members of his gang during the shootout at Union Ice Company. The men made inquiries around town in an attempt to learn as much as they could about their targets. While the hitmen were compiling dossiers on their targets, the targets themselves were conducting their business as usual. Deputies William Bright, Spike Modie, Chester Allen and Norris Stensland didn’t know they were being hunted.

At about 1 a.m. on the morning of March 7, 1923, William Bright and Spike Moody left Sheriff’s headquarters. They climbed into Moody’s Stutz and headed up Broadway. They turned west on Temple and continued down the dark, deserted street. After traveling a few blocks they eyeballed a sedan with the side curtains pulled down. They wouldn’t have paid the automobile much attention except that it was trailing them too closely for their comfort. Knowing that they had enemies in the underworld Moody and Bright readied their weapons. As they prepared themselves for a possible gunfight, Moody and Bright watched the sedan suddenly swing off into a side street and disappear.

A few blocks later the mysterious sedan lurched out of a side street onto Temple and passed the Stutz at a high rate of speed. Moody and Bright saw the side curtains part and a shotgun appear. A second shotgun appeared from the tonneau, the rear passenger compartment of the sedan, and both unleashed a volley fire at Modie and Bright. The deputies pulled out their revolvers and returned fire. Bright fired through the windshield of the Stutz. Fortunately for the deputies, the would-be assassins aim went high when their sedan hit a pothole.

Stutz c. 1923

Moody jammed his foot down on the accelerator and gave chase as the sedan drew away. Bright continued to return fire. Bright may have scored a hit. The sedan skidded across the street into a telephone pole. The sedan sagged with one broken wheel. Three men jumped from the car and fled, but not before firing again at the deputies.

Bright and Moody gave chase on foot but the men vanished into the darkness. Returning to the crippled sedan Bright found a hat with a jagged hole through the crown. The wearer had narrowly escaped death. The hat bore the name of a Chicago hatter.

Sheriff’s investigators located the gunmen’s hotel room. They also identified a few of the shooters acquaintances who, under orders from Sheriff Traeger, were kept under surveillance.

Deputies Bright, Moody, Stensland and Allen prepared themselves for the possibility of another attack–but it never came. The Burton gang seems to have departed Los Angeles forever.

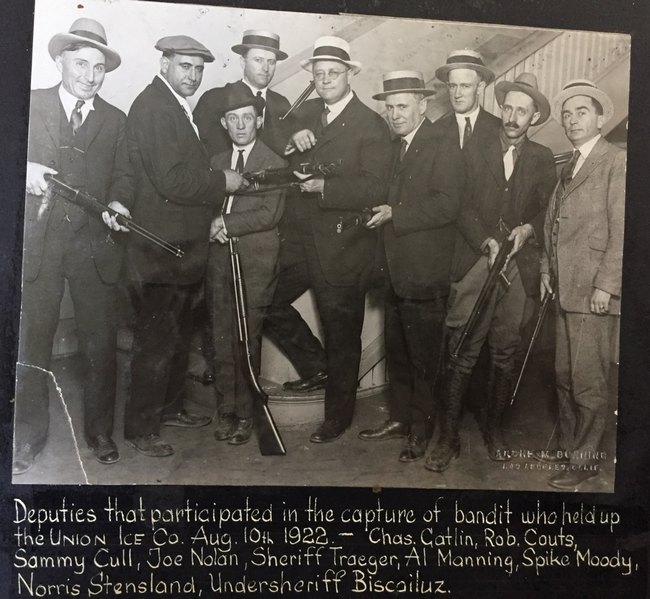

This is such a great photo I decided to post it again!

NOTE: Once again, I am indebted to Mike Fratantoni. His knowledge of L.A.’s law enforcement and criminal history is encyclopedic.

It can be frustrating to pin down accurate spellings of proper names in these historic tales. Often reporters phoned a story into a rewrite person at the newspaper who phonetically spelled a person’s name. Edward Burton was in some reports, Edwin. Another example, Spike Moody’s surname has appeared as Modie. Judging from the above photo it should be the former spelling.