I’m going to turn my attention away from female victims for the time being because I want to focus on the bad girls of L.A.; but before I dig in to individual cases, I want to provide a little background on women behaving badly.

For a wildly entertaining glimpse into female felons behind bars, I highly recommend the 1933 film “Ladies They Talk About”. In fact, let’s consider it as a tutorial for Bad Girls 101.

No Los Angeles jail records exist from the early 1850s until 1888. In February 1888 it was recorded that there were 213 men in jail and only 3 women. The women who were most likely to have been arrested were prostitutes, called “soiled doves”.

Working girls came to the attention of social reformers more often than jailers, and so it went for years. However, the number of female inmates in Los Angeles continued to rise through the 1910s into the 1920s.

In 1926 the new Hall of Justice opened, and prisoners were transferred to the jail that was located on the 9th through the 15th floors. By 1927 the 181 female inmates had outgrown their accommodations on the 13th floor, and the roof chapel had to be converted to a dormitory to handle the overflow.

![Hall of Justice, showing Broadway and Temple St. elevations. Old Hall of Justice showing its south elevation is seen in lower right background, behind county jail. [LAPL Photo]](https://derangedlacrimes.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/01/hojj_1926_00031871-300x235.jpg)

Hall of Justice, showing Broadway and Temple St. elevations. Old Hall of Justice showing its south elevation is seen in lower right background, behind county jail. [LAPL Photo]

In its early days California didn’t have a women’s prison, so the ladies did their time in San Quentin.

The problems with incarcerating women in a primarily male facility are overwhelming. The 17th century English poet Richard Lovelace said:

“Stone walls do not a prison make, Nor iron bars a cage.”

Stone walls and iron bars also make lousy prophylactics.

In the 1870s a female inmate, Nellie Maguire (who’d been convicted of grand larceny) became pregnant while incarcerated at San Quentin. The father of her child was likely a favored inmate who was given free run of the prison.

In 1901 prison reform in California was getting attention from women’s groups, temperance unions, and politicians. It took a couple of decades, and some bitter political battles, but finally in April 1927 the state legislature passed the reformatory bill which authorized $25,000 for site selection for a women’s facility. After months of work a 1,683 acre site in the Tehachapi Mountains was selected for the California Institution for Women.

In August 1933 the first contingent of twenty-eight prisoners left San Quentin for Tehachapi. Finally, in November 1933, all 134 San Quentin women were in their new quarters.

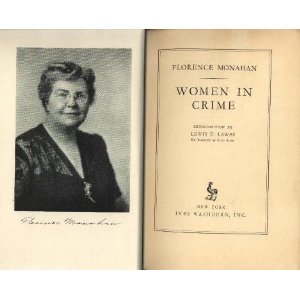

The Superintendent of Tehachapi in the mid/late 1930s was Florence Monahan. Monahan was a long time reformer, and her goal was to release women from Tehachapi who would become self-respecting citizens, instead of bitter, beaten women who would be determined to get back at society.

The Superintendent of Tehachapi in the mid/late 1930s was Florence Monahan. Monahan was a long time reformer, and her goal was to release women from Tehachapi who would become self-respecting citizens, instead of bitter, beaten women who would be determined to get back at society.

Some of the reforms instituted by Monahan included ditching the drab prison uniforms and replacing them with colorful frocks. Monahan said “We plan to revise all clothing. It must be suitable, economical and decent. But why should the women wear something they hate?”

Prisoners were fitted for their new dresses in a sewing room covered with photos torn from the pages of fashion magazines.

The prisoners were no longer required to wear sober footwear in black, white or dark blue. One woman ordered some red sandals from a catalog, and wore them proudly – with everything.

Other freedoms for female inmates included keeping pets, and living in what were referred to as cottages. There were no bars at Tehachapi. And Tehachapi wasn’t only influencing the lives of women doing time there; it was also becoming part of the public consciousness.

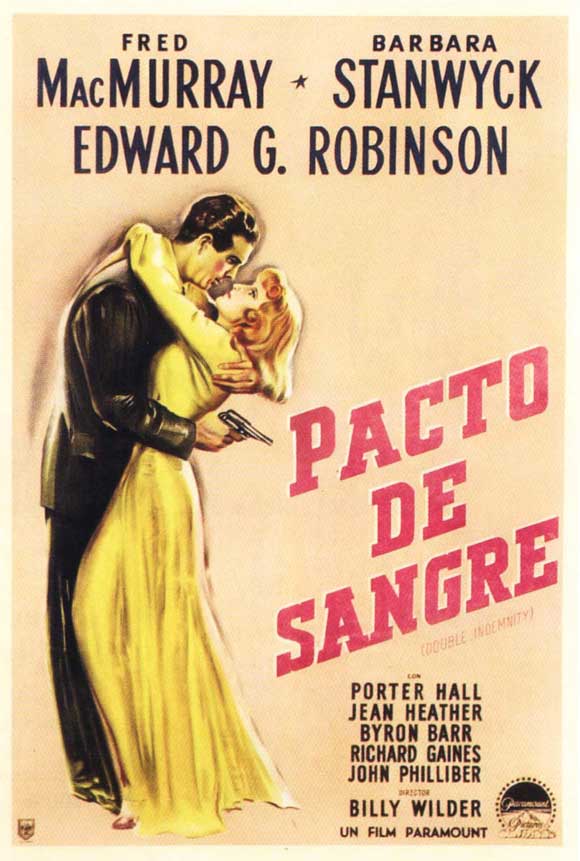

For instance in the 1944 film DOUBLE INDEMNITY, Walter Neff (Fred MacMurray) tries to dissuade Phyllis Dietrichson (Barbara Stanwyck) from carrying out the murder for insurance money plot she’s hatching against her husband by telling her: “….then there was a case of a guy that was found shot. His wife said he was cleaning a gun and his stomach got in the way. All she collected was a 3 to 10 stretch in Tehachapi.”

My favorite film reference to Tehachapi is from the 1941 film, THE MALTESE FALCON. Even though he’s in love with her, Sam Spade (Humphrey Bogart) decides to hand Brigid O’Shaunessy (Mary Astor) over to the cops because she murdered his partner. However, he says that may wait for her: “Well, if you get a good break, you will be out of Tehachapi in 20 years and you can come back to me then. I hope they don’t hang you precious, by that sweet neck.”

There was a significant increase in incarceration rates among women in the mid-1930s, and less than one year following its opening Tehachapi was near capacity.

What kind of woman ended up in Tehachapi? You may be surprised. Ninety percent of the women were first time offenders, and fourteen percent of them had been convicted of murder! Their median age was 37, and eighty percent of them were Caucasian. Nearly half of the inmates came from Los Angeles!

Is there something about Los Angeles that brings out the evil in a woman? Crime writer Raymond Chandler speculated that a local weather phenomenon could cause a woman to contemplate murder. He wrote:

“There was a desert wind blowing that night. It was one of those hot dry Santa Anas that come down through the mountain passes and curl your hair and make your nerves jump and your skin itch. On nights like that every booze party ends in a fight. Meek little wives feel the edge of the carving knife and study their husbands’ necks. Anything can happen. You can even get a full glass of beer at a cocktail lounge.”

The stock market crashed in October of 1929 and flapper bandits gave way to gun molls and Tommy guns.

The Depression of the 1930s resulted in the perpetration of darker crimes. Women became involved in bandit gangs – they didn’t stay at home and roll bandages for the wounded thugs in their lives, they were active participants in kidnappings, bank robberies, and murders.

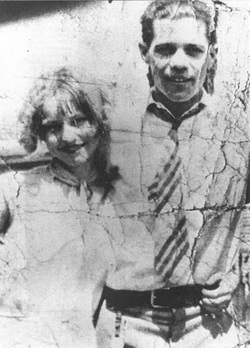

Many of the most notorious gangs of the Depression operated out of the mid-west. Everyone has heard of Clyde Barrow and Bonnie Parker.

Bonnie took an active role in the Barrow Gang’s misdeeds, and she had no illusions about how she and Clyde would end their days. The last few lines of her poem THE BALLAD OF BONNIE AND CLYDE read:

They don’t think they’re tough or desperate

They know the law always wins

They’ve been shot at before, but they do not ignore

That death is the wages of sin.

BONNIE & CLYDE

Some day they’ll go down together

And they’ll bury them side by side

To few it’ll be grief, to the law a relief

But it’s death for Bonnie and Clyde.

How did Bonnie & Clyde pay the wages of sin?

During 1933, before they died in a hail of bullets, Bonnie & Clyde were on the run from the law in the Midwest. L.A. had a criminal duo too, Burmah and Thomas White.

NEXT TIME: L.A.’s own Bonnie & Clyde: Burmah & Thomas White.

![Aggie Underwood interviews a mourner at the funeral of L.A. evangelist Aimee Semple McPherson. [Photo courtesy LAPL.]](https://derangedlacrimes.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/01/00034796-240x300.jpg)

![Welby Hunt and William Hickman [Photo is courtesy of LAPL.]](https://derangedlacrimes.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/01/00027806_HICKMAN_HUNT-300x285.jpg)