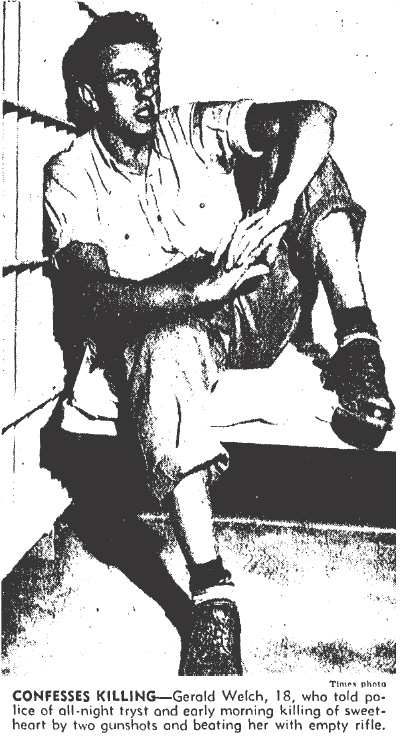

Pasadena police were stunned when, early on the morning of April 19, 1947, 18-year-old Gerald Snow Welch arrived with the dead body of a girl in his car. He coolly announced to officers his “purpose in life has been completed.” What in the hell was he talking about? Who was the girl and how had she died?

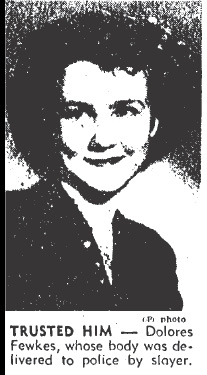

Gerald identified the girl as his 16-year-old sweetheart Dolores Fewkes. He claimed that he and Dolores had planned to die together but he survived due to a miscalculation on his part. He had brought only two bullets with him to the deserted picnic grounds in the San Gabriel Mountains where the couple planned to leave this world behind. He thought two rounds would be enough, but when Dolores failed to die immediately after the first bullet entered her head, he fired again. The second round entered her skull about a half an inch from the first, but it didn’t kill her either. She started to scream and wouldn’t stop. He told police that he “finished her off” by battering her to death with the stock and barrel of the .22. “If only I had taken more bullets…” he told police. Once Dolores was dead he put her bloody body into his car and drove her to the police station where he confessed.

Gerald identified the girl as his 16-year-old sweetheart Dolores Fewkes. He claimed that he and Dolores had planned to die together but he survived due to a miscalculation on his part. He had brought only two bullets with him to the deserted picnic grounds in the San Gabriel Mountains where the couple planned to leave this world behind. He thought two rounds would be enough, but when Dolores failed to die immediately after the first bullet entered her head, he fired again. The second round entered her skull about a half an inch from the first, but it didn’t kill her either. She started to scream and wouldn’t stop. He told police that he “finished her off” by battering her to death with the stock and barrel of the .22. “If only I had taken more bullets…” he told police. Once Dolores was dead he put her bloody body into his car and drove her to the police station where he confessed.

He told investigators that he felt “no sorrow, no regrets” about the slaying and was convinced that Dolores was surely in heaven awaiting his arrival. “There won’t ever be any change in my feelings. I loved her and she wanted to go with me into the next world. It will be much happier and better there.” Then he explained that he’d rather let the State kill him but: “…I would kill myself if I got the chance.” Gerald appeared to be in no hurry to make good on his threat, he sat on the bunk in his jail cell and stared at the ceiling.

He admitted that when he originally contemplated suicide he had no intention of taking Dolores with him but: “She said she couldn’t stand to be left behind and we decided to go together.”

He admitted that when he originally contemplated suicide he had no intention of taking Dolores with him but: “She said she couldn’t stand to be left behind and we decided to go together.”

What had driven the teenagers to consider such drastic action? Were teenage angst or raging hormones to blame? Gerald explained that his suicidal thoughts were the result of a crisis of faith coinciding with his medical discharge from the Navy where he had served “three unhappy months.”

“I began to doubt a lot of things which had been told me in Sunday School and church and I began to do some investigations. I went to the library and I read philosophers–lots of them–Plato, and Schopenhauer and Emerson. I found in Schopenhauer a positive justification for suicide.”

Strange as they were Gerald had given his reasons for wanting to die, but his contention that Dolores couldn’t bear to be left behind needed further examination. Everyone who knew the Montebello High School student said that she was a happy girl with a lot to live for. Did she have a secret dark side that she had revealed only to Gerald? Had she willingly entered into a suicide pact with him, or was he lying?

NEXT TIME: Dolores’ family disputes Gerald’s story that she wanted to die with him and accuses him of cold-blooded murder.

Russell Thompson refused to believe that his daughter, 7-year-old Alsa, had poisoned anyone. Dr. Edwin Huntington Williams, a psychiatrist, was inclined to agree with him. The doctor examined Alsa and pronounced her abnormal but “…not exactly insane.” He said: “It might be that in periods of epilepsy she has done strange things but it will take much careful observation to determine what is wrong with her. I have made only a casual examination but will make a more detailed one with Dr. Martin G. Carter, superintendent of the Psychopathic Hospital, and Dr. G.H. Steele, assistant superintendent.”

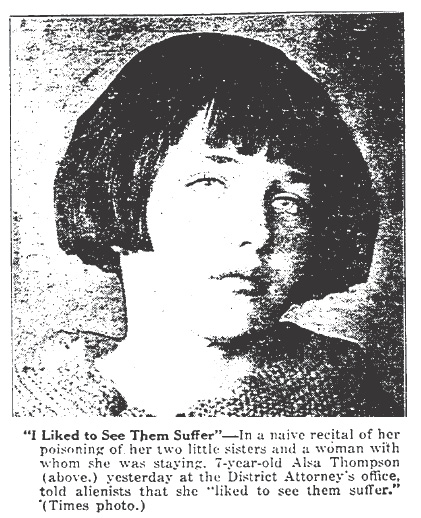

Russell Thompson refused to believe that his daughter, 7-year-old Alsa, had poisoned anyone. Dr. Edwin Huntington Williams, a psychiatrist, was inclined to agree with him. The doctor examined Alsa and pronounced her abnormal but “…not exactly insane.” He said: “It might be that in periods of epilepsy she has done strange things but it will take much careful observation to determine what is wrong with her. I have made only a casual examination but will make a more detailed one with Dr. Martin G. Carter, superintendent of the Psychopathic Hospital, and Dr. G.H. Steele, assistant superintendent.” Psychiatrists declared that Alsa was sane. Buron Fitts, the Chief Deputy District Attorney, didn’t seem to know what make of the girl. He said: “Frankly, I don’t know what to think. It’s the most extraordinary case I ever heard of. I don’t know whether to believe the child or not. Her stories sound improbable, but then there is the way she tells them. I just don’t what to think about it yet.”

Psychiatrists declared that Alsa was sane. Buron Fitts, the Chief Deputy District Attorney, didn’t seem to know what make of the girl. He said: “Frankly, I don’t know what to think. It’s the most extraordinary case I ever heard of. I don’t know whether to believe the child or not. Her stories sound improbable, but then there is the way she tells them. I just don’t what to think about it yet.” On February 3, 1925 a bizarre story broke in the local news — it was alleged that seven year old Alsa Thompson had attempted to murder a family of four with a mixture of sulphuric acid and ant paste she had added to the evening meal. The intended victims tasted the food, but it was so awful they pushed their plates away.

On February 3, 1925 a bizarre story broke in the local news — it was alleged that seven year old Alsa Thompson had attempted to murder a family of four with a mixture of sulphuric acid and ant paste she had added to the evening meal. The intended victims tasted the food, but it was so awful they pushed their plates away. Alsa was taken by Policewoman Elizabeth Feeley to the Receiving Hospital where she was questioned by police and surgeons about the poisoning plot. The little girl cheerfully confessed that she had indeed attempted a quadruple homicide and that she’d done it because: “…I am so mean.”

Alsa was taken by Policewoman Elizabeth Feeley to the Receiving Hospital where she was questioned by police and surgeons about the poisoning plot. The little girl cheerfully confessed that she had indeed attempted a quadruple homicide and that she’d done it because: “…I am so mean.”