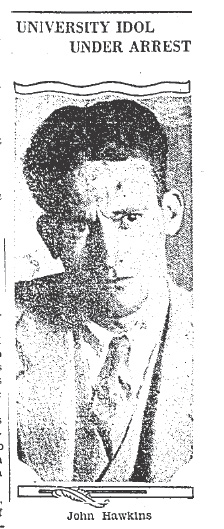

Former USC football idol, Johnny Hawkins, was arrested for burglary in the home of Biltmore orchestra leader, Earl Burnett. They found him in the living room holding a flashlight and listening to the radio. Hawkins immediately confessed to over two dozen residential burglaries over the period of a few months, and he told the police that he had committed the crimes because he was desperate for money, in part because his wife had major medical bills.

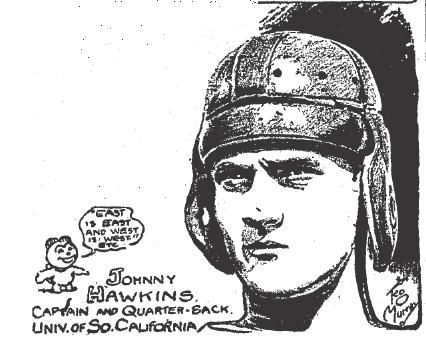

Hawkins was about the last guy anyone would expect to turn to crime. He had been the captain and quarterback of the USC football team. In fact, he was an all-around fine athlete playing football, baseball, and basketball with equal skill. He could have had a career in any of the sports in which he excelled, but the first couple of years following his graduation from college had proved difficult for Johnny.

Cops were baffled when Johnny led them to the attic of his parent’s Fullerton home and showed them his ill-gotten loot because he had tried to sell none of the items. If he desperately needed money, why would he have kept the loot?

Another odd wrinkle in the case came when it was discovered that about a week before Johnny’s arrest, one of his younger brothers, Jimmy, was taken into custody for grand theft.

In early June 1928, just days prior to Johnny’s arrest, Jimmy Hawkins stopped in at the home of Mrs. Betty Sheridan on Normandie Avenue. While Betty was on the telephone with her sister, Jimmy disappeared, taking with him $1500 worth of her jewelry. It isn’t clear how Jimmy became acquainted with Betty. She said she knew his father was a prominent citizen in Fullerton, but didn’t seem to know anything else about the young man or his background.

While he was cooling his heels in a jail cell, he got a visitor, Johnny. Johnny delivered a severe lecture to his sibling and convinced the younger man to return the stolen jewelry. The D.A. declined to press charges, and released Jimmy.

Unfortunately, Johnny’s encounter with the law didn’t go as well as his brother’s had. They charged him with thirty-one counts of burglary. If Johnny thought his life couldn’t get any worse, he was wrong. The law arrested Johnny’s brother, again. This time, it was as an accomplice.

The L.A. Times likened Johnny to Fagin, the receiver of stolen goods and leader of a group of thieving children in the Charles Dickens novel “Oliver Twist.” Not a flattering comparison, and it showed how far Johnny had fallen, at least in the eyes of the press.

Jimmy didn’t hold up well under interrogation, and he confessed. He shifted the bulk of the blame onto his older brother. He told cops when he became unwilling to continue the residential crime spree, Johnny became domineering and forced him to continue the illicit activities.

Johnny hired an attorney, Joe Ryan, who appeared to believe in his client. Hawkins confided in Ryan he was stealing because he was seized by an uncontrollable mania, which he believed had been caused by an injury to his head while playing football. He had a lump over his left eye that may have been the outward sign of severe brain trauma.

Johnny finally got a piece of good news when his brother Jimmy recanted his confession. Jimmy said,

“I was so sleepy. They (the cops) wouldn’t let me sleep for two nights and I didn’t know what I was signing.”

In August 1928, Johnny Hawkins appeared in Superior Court to plead guilty to five out of thirty-one counts of burglary and to apply for probation so he might avoid a prison term. Hawkins’ attorney, Joe Ryan, told the court that his client was under the care of Dr. Cecil Reynolds, a brain specialist, who intended to perform brain surgery to relieve pressure believed to have been caused by a football injury. The injury on which Johnny blamed his recent criminal tendencies.

While awaiting a probation hearing, Johnny fainted. He fell to the concrete floor of the attorney’s room in the jail and received another serious head injury.

Despite the argument that his repeated head injuries had caused Hawkins to pursue a brief life of crime, there was no recommendation for probation, and Superior Judge Fricke sentenced the former college gridiron great to from five to seventy-five years in prison.

Given an opportunity to address the court, Johnny said, “Don’t you think I would be a respectable citizen after all this trouble if I were given another chance?”

To which Judge Fricke replied, “I am sorry, but I am not certain that you would be.”

After the pronouncement of sentence, Johnny shook hands with his counsel, who was also a friend of his from his glory days at USC, then bowed his head and walked from the courtroom manacled to a deputy sheriff.

Nothing ever came of the brain operation that Johnny had hoped for.

Hawkins served twenty-nine months in San Quentin before they paroled him. For seven years following his release, he held a position in M.G. M’s art department; he even coached the studio basketball team to championships.

On May 22, 1939, thirty-seven-year-old Johnny Hawkins died of an apparent brain abscess. Dr. Louis Gogol, assistant county autopsy surgeon, stated that in his opinion the injury Johnny had received while playing football at USC was the probable reason for the string of burglaries that he’d committed eleven years earlier. He said that the previous injury was undeniably the cause of his premature death.

Death verified Johnny Hawkins’ innocence, yet shockingly, very little has changed. Other than repeated brain trauma, the risk factors for chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) remain unknown. The disease can only be accurately diagnosed postmortem.