This month is an important one for the Deranged L.A. Crimes blog. It is the twelfth anniversary of the blog.

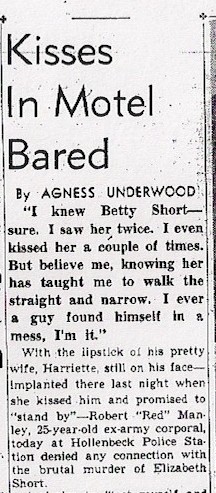

December 17, 2012 (the 110th anniversary of the birth of the woman whose career and life inspires me, Agness “Aggie” Underwood) I created the blog. I also authored her Wikipedia page, which was long overdue. I felt it was important to honor her on the anniversary of her birth. I’ve been trying to keep her legacy alive ever since.

By the time I began, Aggie had been gone for twenty-eight years. I regret not knowing about her in time to meet her in person. But, through her work, and speaking with her relatives over the years, I feel like I know her. I have enormous respect for Aggie. She had nothing handed to her, yet she established herself in a male-dominated profession where she earned the respect of her peers without compromising her values. She also earned the respect of law enforcement. Cops who worked with her trusted her judgement and sought her opinion. It isn’t surprising. She shared with them the same qualities that make a successful detective.

Aggie never intended to become a reporter. All she wanted was a pair of silk stockings. She’d been wearing her younger sister’s hand-me-downs, but she longed for a new pair of her own. When her husband, Harry, told her they couldn’t afford them, she threatened to get a job and buy them herself. It was an empty threat. She did not know how to find employment. She hadn’t worked outside her home for several years. A serendipitous call from her close friend Evelyn, the day after the stockings kerfuffle, changed the course of her life. Evelyn told her about a temporary opening for a switchboard operator where she worked, at the Los Angeles Record. Aggie accepted the temporary job, meant to last only through the 1926-27 holiday season.

Aggie arrived at the Record unfamiliar with the newspaper business, but she swiftly adapted and everyone realized, even without training, she was sharp and eager to learn. The temporary switchboard job turned into a permanent position.

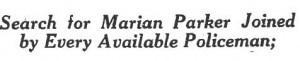

In December 1927, the kidnapping and cruel mutilation murder of twelve-year-old schoolgirl Marion Parker horrified the city. Aggie was at the Record when they received word the perpetrator, William Edward Hickman, who had nicknamed himself “The Fox,” was in custody in Oregon. The breaking story created a firestorm of activity in the newsroom. Aggie had seen nothing like it. She knew then she didn’t want to be a bystander. She wanted to be a reporter.

When the Record was sold in January 1935, Aggie accepted an offer from William Randolph Hearst’s newspaper, the Evening Herald and Express, propelling her into the big leagues. Hearst expected his reporters to work at breakneck speed. After all, they had to live up to the paper’s motto, “The First with the latest.”

From January 1935, until January 1947, Aggie covered everything from fires and floods to murder and mayhem, frequently with photographer Perry Fowler by her side. She considered herself to be a general assignment reporter, but developed a reputation and a knack for covering crimes.

Sometimes she helped to solve them.

In December 1939, Aggie was called to the scene of what appeared to be a tragic accident on the Angeles Crest Highway. Laurel Crawford said he had taken his family on a scenic drive, but lost control of the family sedan on a sharp curve. The car plunged over 1000 feet down an embankment, killing his wife, three children, and a boarder in their home. He said he had survived by jumping from the car at the last moment.

When asked by Sheriff’s investigators for her opinion, Aggie said she had observed Laurel’s clothing and his demeanor, and neither lent credibility to his account. She concluded Laurel was “guilty as hell.” Her hunch was right. Upon investigation, police discovered Laurel had engineered the accident to collect over $30,000 in life insurance.

Hollywood was Aggie’s beat, too. When stars misbehaved or perished under mysterious or tragic circumstances, Aggie was there to record everything for Herald readers. On December 16, 1935, popular actress and café owner Thelma Todd died of carbon monoxide poisoning in the garage of her Pacific Palisades ho9me. Thelma’s autopsy was Aggie’s first, and her fellow reporters put her to the test. It backfired on them. Before the coroner could finish his grim work, her colleagues had turned green and fled the room. Aggie remained upright.

Though Aggie never considered herself a feminist, she paved the way for female journalists. In January 1947, they yanked her off the notorious Black Dahlia murder case and made her city editor—one of the first woman to hold the post for a major metropolitan newspaper. Known to keep a bat and starter pistol handy at her desk, she was beloved by her staff and served as city editor for the Herald (later Herald Examiner) until retiring in 1968.

When she passed away in 1984, the Herald-Examiner eulogized her. “She was undeterred by the grisliest of crime scenes and had a knack for getting details that eluded other reporters. As editor, she knew the names and telephone numbers of numerous celebrities, in addition to all the bars her reporters frequented. She cultivated the day’s best sources, ranging from gangsters and prostitutes to movie stars and government officials.”

I have pondered how appalled Aggie would be at what passes for journalism today. During her lifetime, she disdained anyone unwilling to get out and scrap for a story. Today she would find herself surrounded by people who call their personal opinions news, and their writings (multiple misspellings and grammatical atrocities included), reporting.

In a world where oligarchs bend once respected publications to their perverted will, Aggie would be unwelcome.

Don’t misunderstand me—even in Aggie’s day, newspapers were not owned by paupers, and they all had an editorial agenda. But when it came to reporting hard news, it was all about the facts. There was no such thing as fake news or “alternative” facts (what does that even mean?!)

Today we must look hard to find facts. Legacy media has failed us in all of its forms. Losing reliable media puts our country at significant risk.

I suppose my anger, disenchantment, and disgust with the current state of media is why I honor Aggie’s legacy. She represents the best of what reporters once were, and what they could be again if not constrained by fear. The newspaper & TV owners seem to be motivated by a mixture of fear and greed. It is not the way to maintain a free press. We can all do better.

Happy Birthday, Aggie, and Deranged L.A. Crimes!

Best,

Joan

Why was Marion on a crime spree? He told reporters: “I wanted to commit self-destruction in such a way my insurance policy would not be invalidated through the suicide clause.” Suicide by cop would have been his parents the princely sum of $1200 (equivalent to $20,814.77 in current USD). No doubt the cash would have helped his family weather the Depression. Marion entered a guilty plea, but a few days later he reappeared in court and changed his plea to innocent. He was placed on probation for 2 years.

Why was Marion on a crime spree? He told reporters: “I wanted to commit self-destruction in such a way my insurance policy would not be invalidated through the suicide clause.” Suicide by cop would have been his parents the princely sum of $1200 (equivalent to $20,814.77 in current USD). No doubt the cash would have helped his family weather the Depression. Marion entered a guilty plea, but a few days later he reappeared in court and changed his plea to innocent. He was placed on probation for 2 years.

Marion was convicted of voluntary manslaughter. Judge Henry A. Hicks pronounced sentence–from seven to eight years in the state penitentiary. Lewis D. Mowry, Marion’s attorney, said that the his client had no plans to appeal, nor would he seek a new trial.

Marion was convicted of voluntary manslaughter. Judge Henry A. Hicks pronounced sentence–from seven to eight years in the state penitentiary. Lewis D. Mowry, Marion’s attorney, said that the his client had no plans to appeal, nor would he seek a new trial. By December 1927 twenty-three-year-old Ruth Malone had been in Los Angeles for about 4 months. She’d fled Aberdeen, Washington to escape her husband John, a jealous and violent drunk. She used her mother’s address at 244 North Belmont Avenue, but lived with a girl friend in an apartment at 9th and Flower. She kept the address of the apartment a secret just in case John tried to find her. She worked half a mile from the apartment at a drug store on East Twelfth between Santee Street and Maple Avenue. Ruth had spent the last few months seriously contemplating divorce but she wasn’t in any hurry to confront John.

By December 1927 twenty-three-year-old Ruth Malone had been in Los Angeles for about 4 months. She’d fled Aberdeen, Washington to escape her husband John, a jealous and violent drunk. She used her mother’s address at 244 North Belmont Avenue, but lived with a girl friend in an apartment at 9th and Flower. She kept the address of the apartment a secret just in case John tried to find her. She worked half a mile from the apartment at a drug store on East Twelfth between Santee Street and Maple Avenue. Ruth had spent the last few months seriously contemplating divorce but she wasn’t in any hurry to confront John.

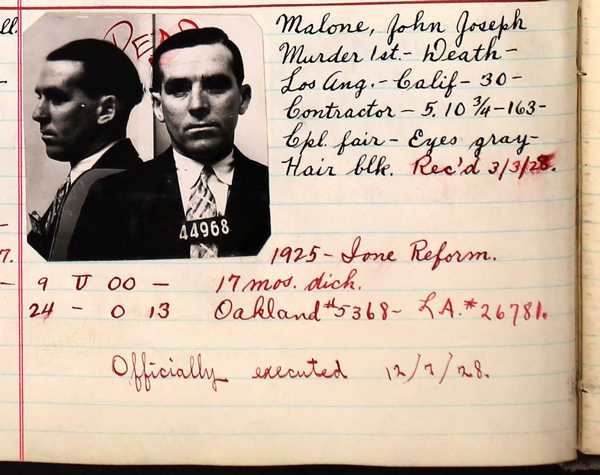

Investigators learned that John was 29-years-old and that he had an arrest record. He’d been busted in Oakland on October 10, 1917 on a burglary charge and later in San Francisco for violation of the State Poison Act (a drug charge). John had been in Los Angeles for a few weeks. He was staying at a hotel just a few blocks away from Ruth’s workplace.

Investigators learned that John was 29-years-old and that he had an arrest record. He’d been busted in Oakland on October 10, 1917 on a burglary charge and later in San Francisco for violation of the State Poison Act (a drug charge). John had been in Los Angeles for a few weeks. He was staying at a hotel just a few blocks away from Ruth’s workplace. On March 20, 1928 John and several other death row inmates welcomed a newcomer to their ranks, William Edward Hickman. Hickman, who had given himself the nickname “The Fox” had been sentenced to death for the brutal mutilation murder of 12-year-old Marion Parker, a crime he had committed only ten days after John had killed Ruth. The two dead men walking had met in the Los Angeles County Jail while each was awaiting trial. John cornered Hickman on one occasion and blamed him for inciting the public to a renewed interest in capital punishment–resulting in his own date with the hangman.

On March 20, 1928 John and several other death row inmates welcomed a newcomer to their ranks, William Edward Hickman. Hickman, who had given himself the nickname “The Fox” had been sentenced to death for the brutal mutilation murder of 12-year-old Marion Parker, a crime he had committed only ten days after John had killed Ruth. The two dead men walking had met in the Los Angeles County Jail while each was awaiting trial. John cornered Hickman on one occasion and blamed him for inciting the public to a renewed interest in capital punishment–resulting in his own date with the hangman. John’s sentence was automatically appealed but the State Supreme Court upheld the death penalty. Judge Fricke re-sentenced John to hang. Unless something changed he would meet his end on December 7, exactly one year to the day since Ruth’s murder. John had evidently changed his mind about dying since his suicide attempt because he was part of a Thanksgiving escape plot that failed. To prevent him from any further attempts to tunnel out of San Quentin he was moved to the death cell.

John’s sentence was automatically appealed but the State Supreme Court upheld the death penalty. Judge Fricke re-sentenced John to hang. Unless something changed he would meet his end on December 7, exactly one year to the day since Ruth’s murder. John had evidently changed his mind about dying since his suicide attempt because he was part of a Thanksgiving escape plot that failed. To prevent him from any further attempts to tunnel out of San Quentin he was moved to the death cell.