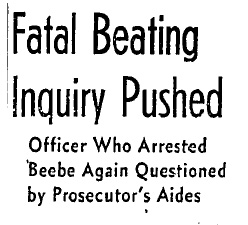

The alleged beating death of Stanley Beebe while he was in custody resulted in more than just a public relations crisis for the LAPD. Citizens were outraged and leery of their police department, especially when other cases of alleged police brutality began to surface.

The alleged beating death of Stanley Beebe while he was in custody resulted in more than just a public relations crisis for the LAPD. Citizens were outraged and leery of their police department, especially when other cases of alleged police brutality began to surface.

Mayor Bowron and the City Council joined the District Attorney in demanding a full investigation. None of the politicos wanted to be perceived as soft on police brutality. Besides, any heat brought to bear on the power structure of the city might reveal pay-offs and other nefarious goings-on and that just wouldn’t do.

The Mayor issued a statement in which he said that a full investigation would be made, and the Council adopted a resolution asking the Board of Police Commissioners to investigate and supply additional information involving the possible beating of a blind man by LAPD officers.

Another man, Mr. James M. Palmer, 63, a janitor at the Philharmonic Auditorium Building came forward and charged that two police radio officers beat him over the head with a blackjack and kicked him after they had arrested him on a charge of intoxication. The records showed that Palmer was booked by Officers Francis B. Doyle and Edward L. Burnett early on the morning of January 4, 1943. Doyle and Burnett told one of the D.A.’s investigators, B.G. Haworth, that they’d gotten an anonymous call, shortly after 1 a.m., informing them that a man was lying on the sidewalk near 433 S. Olive Street and when they arrived at the scene they had found Palmer in a drunken stupor.

Palmer denied that he’d been drinking. In fact his story was substantively different from that of the two cops. Palmer claimed that he’d gone to a drugstore about midnight to get some medicine when he was seized and beaten by two police officers at Fifth and Hill Streets. He was thrown into a black and white patrol car and driven around for a while as the two officers took turns choking and kicking him.

Officers Doyle and Burnett suddenly came down with amnesia–they said they had no recollection of an incident like the one described by Palmer. The investigation was tough going–eight policemen and two jail trusties who had worked the fingerprint room on the night of Stanley Beebe’s incarceration in Central Jail were interviewed. Initially Sergeant Rudolph C. Kucera, made a report to Captain James E. Irwin in which he stated that when he saw Stanley Beebe he looked like he had been beaten–yet when the D.A.’s investigators came around none of them recalled any complaints or beatings. Amnesia was apparently endemic among certain officers in the LAPD.

Assistant D.A. Clyde Shoemaker, who had initiated the investigation into Palmer’s charges said he was puzzled by the discrepancies in the statements and he let it be known that he’d like to speak with any witnesses.

“If anyone was in the vicinity of Fifth and Hill Streets that morning and saw any disturbance, I would like to have them tell me about it. We are going to continue this investigation until we have arrived at the truth as to what happened.”

Councilman G. Vernon Bennett introduced a resolution at a council meeting:

“Moved that the Board of Police Commissioners be requested to make a thorough investigation of alleged police brutality in the Beebe affair and in the alleged mistreatment of Clark Stamper, a blind worker from the Industrial Workshop for the Blind, apprehended at Seventh and Hill Streets at 11:30 p.m. on his way from work: also in the alleged police beating of James M. Palmer, a watchman 63 years of age.”

Councilman Edward L. Thrasher stated that some older police officers had told him that new vice-squad policemen were running rough-shod over vice suspects booked at the Lincoln Heights Jail:

“The picture as presented to me is that these overzealous young men beat and strike these prisoners, being careful to hit them in the stomach or other places where the blows will not leave marks.”

Mayor Bowron weighed in on the allegations of brutality:

“The matter of alleged police brutality is causing me much serious concern. I do not countenance this thing any more than any good citizen of Los Angeles. There has been an unfortunate death under circumstances that make it appear a crime has been committed. That the deceased came to his death as the result of a violent blow there can be no doubt. The question is how was the blow inflicted and by whom.

“The investigation now under way will be thorough and complete. There will be no covering up, there will be no buck passing. Whoever is guilty will be brought to justice but there will be no scapegoat.”

One of the officers called to the D.A.’s office to make a statement was John M. Yates. He had been on duty at the booking desk the night Stanley Beebe had been brought in. Officer Yates failed to grasp the importance of being on your best behavior during an investigation into police brutality. When newspaper photographer Edward Phillips snapped a photo of him the enraged officer kicked the photographer in the balls.

One of the officers called to the D.A.’s office to make a statement was John M. Yates. He had been on duty at the booking desk the night Stanley Beebe had been brought in. Officer Yates failed to grasp the importance of being on your best behavior during an investigation into police brutality. When newspaper photographer Edward Phillips snapped a photo of him the enraged officer kicked the photographer in the balls.

Yates offered a creative explanation for the kicking incident. He said that he’d already been semi-blinded by one photographer’s flash bulb, so when Phillips set off another in his face he started to fall backward. As he struggled to regain his balance his foot flew upward and somehow Phillips fell testicles first onto the upraised foot.

Yates offered a creative explanation for the kicking incident. He said that he’d already been semi-blinded by one photographer’s flash bulb, so when Phillips set off another in his face he started to fall backward. As he struggled to regain his balance his foot flew upward and somehow Phillips fell testicles first onto the upraised foot.

Within four hours of the incident Yates was suspended and ordered to face a trail before a police board of rights.

The investigation of police brutality had turned into a cluster fuck. Officials from Mayor Bowron’s office and from the LAPD were tripping over each other, but whether it was to do the right thing or obfuscate wasn’t entirely clear. Finally D.A. Dockweiler couldn’t take it anymore and ousted all police and city officials who had been involved in the inquiry and announced that his staff alone would undertake the investigation. Dockweiler called it “bad psychology” to expect accurate information from jail trusties, policemen and citizens called as witnesses when they would have to testify in the presence of high ranking police officials.

It’s no wonder some of the witnesses were reluctant to speak. Deputy City Attorney Everett Leighton’s wife picked up their home phone and a man speaking in a gruff voice said:

“If you want that big-mouthed husband of yours to stay alive, tell him to keep his mouth shut.”

Earlier that day Leighton had spoken with Deputy District Attorney Robert Wheeler, the man in charge of the investigation, and told him that when Stanley Beebe had appeared in court at City Jail on the morning after his arrest on intoxication charges he:

“…looked like he had been through a meat grinder. His face was red and puffy. His eyes were swollen so that he seemed to have difficulty in seeing, but they were not discolored.”

Leighton’s statement corroborated that of Mrs. Martha Hamilton, court reporter, who had been on the job the day of Beebe’s court appearance.

None of the D.A’s investigators had been able to break down the cops they interviewed. Without exception police witnesses stated that Beebe showed no indications of any injuries at any time.

In his deathbed statement Stanley Beebe was unable to name his attacker but described him to his wife as a “tall blonde man”. Without a break in the case it was likely that at least one bad cop, maybe more, would get away with murder.

NEXT TIME: The investigation continues.

![LAPD Chief C.B. Horrall inspecting Detective Division c. 1947. [Photo courtesy UCLA Digital Collection.]](https://derangedlacrimes.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/horrall.jpg)

![George Dazey on the witness stand. [Photo courtesy of UCLA digital collection]](https://derangedlacrimes.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/george-witness-stand.jpg)