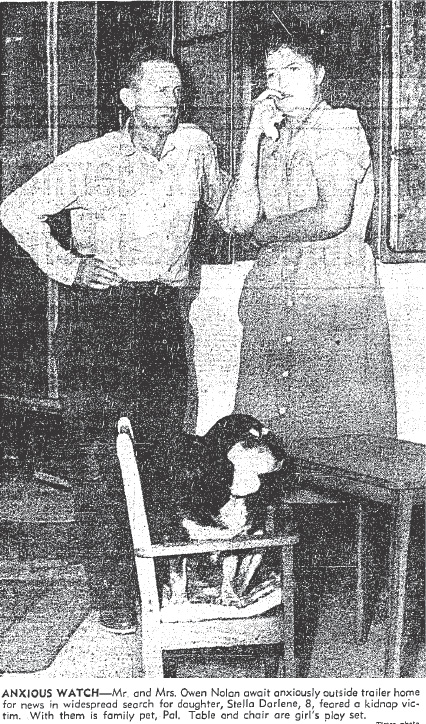

Ilene and Owen Nolan struggled to get on with their lives in the wake of Stella’s disappearance. They moved to the San Diego area, but I imagine that every time the story of a missing or abused child made the news their hearts broke a little more.

Sherriff’s deputies and LAPD investigators continued to pull in every deviant who even looked cross-eyed at a child. They busted other child molesters, but they couldn’t seem to get a break in Stella’s case which grew colder with every passing day.

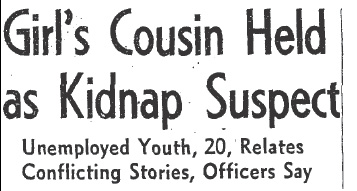

In December 1955, Sheriff’s deputies interrogated Robert Louis Kracker, 20, on suspicion of kidnapping a 3-year-old Baldwin Park girl, Cynthia Hardacre. Kracker had been visiting a cousin in the Hardacre neighborhood when Cynthia, apparently mistaking Robert for her father, dashed toward his automobile calling, “Wait, Daddy.” Kracker told the police

that: “When I saw her, something just came over me.”

Kracker was on parole and had a record, including sex offenses, going back to age 14! In 1949 he spent three months in Juvie and was subsequently committed to the State Hospital at Camarillo. In July of 1950, he was arrested in L.A. on suspicion of a sex offense, and in November, 1951 he was arrested on suspicion of burglary.

Robert was guilty of the attack on Cynthia, but he was not responsible for Stella’s abduction.

In August of 1961 the L.A. Times reported on five children who had mysteriously vanished in recent years; Stella’s name was among them.

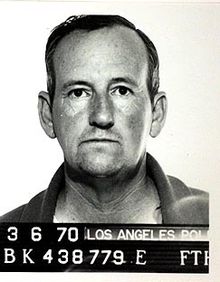

On March 6, 1970 a 51-year-old Sylmar construction worker, Mack Ray Edwards, appeared at the LAPD’s Foothill Division station. He handed them a loaded handgun and then said the had kidnapped three Sylmar girls earlier that day.

Edwards, a native of Arkansas, was booked on suspicion of murder in the 1969 death of a 13-year-old Pacoima boy — one of the six cases he voluntarily discussed with detectives.

Edwards, a native of Arkansas, was booked on suspicion of murder in the 1969 death of a 13-year-old Pacoima boy — one of the six cases he voluntarily discussed with detectives.

Edwards and an unnamed 15-year-old companion told the police that they’d entered the home of Mr. and Mrs. Edgar Cohen at 5 a.m., after the couple had left for work. The two stole a coin collection and other items from the house and then took the three Cohen children, Valerie (12); Cindy (13); and Jan (14) by car to Bouquet Canyon in Angeles National Forest north of Newhall.

Edwards and an unnamed 15-year-old companion told the police that they’d entered the home of Mr. and Mrs. Edgar Cohen at 5 a.m., after the couple had left for work. The two stole a coin collection and other items from the house and then took the three Cohen children, Valerie (12); Cindy (13); and Jan (14) by car to Bouquet Canyon in Angeles National Forest north of Newhall.

Two of the girls escaped and the third was abandoned by Edwards and his accomplice — they told her they’d send a sheriff’s car to pick her up.

It was during his confession to police that he admitted to kidnapping, raping, and then murdering 8-year-old Stella Darlene Nolan in 1953. The girl was allegedly his first murder victim.

In mid-March 1970, the skeletal remains of Stella Darlene Nolan were unearthed by a highway crew who worked from directions given to them by her killer.

In addition to the slaying of Stella, Edwards admitted to murdering Gary Rocha, 16, in 1968, and Donald Allen Todd, 13, in 1960. He also admitted to three other murders of children but he wasn’t charged with them because their bodies couldn’t be found. Edwards was a heavy machine operator and often worked freeway construction sites, it simply wasn’t possible for the law to go around digging up Southern California freeways in an effort to unearth the other remains.

In Van Nuys Superior Court, Edwards entered a plea of guilty in three of the six slayings to which he had confessed. Sgt. George H. Rock was called to testify about Edwards’ voluntary admission that he was a child killer. All of the murders were horrible, but Stella’s was the worst. Edwards had taken her from Auction City in Norwalk to his Azusa home where he molested and then attempted to strangle her. After he thought Stella was dead, he threw her body over bridge. The following day he returned to the scene to bury his victim and found the little girl still alive. She had managed to drag herself about 100 feet. She was sitting up, dazed, when Edwards took out his pocketknife and stabbed her to death.

Edwards attempted to sell his surrender and confession as a guilty conscience. He said:

“I have a guilt complex. I couldn’t eat and I couldn’t sleep and it was beginning to affect my work. You know I’m a heavy equipment operator. That long grader I’m using now costs a lot of money — $200,000. I might wreck it. Or turn it over and hurt someone.”

That doesn’t sound like a guilty conscience to me — it sounds exactly like the kind of profoundly stupid, self-serving statement a sociopath would make. There was no expression of remorse for his victims, his primary concern appears to have been the deleterious affect the brutal child killings were having on his work.

Edwards claimed to want a death sentence. Maybe he did — he attempted suicide twice during his trial. On March 30, 1970 he slashed a 14-inch cut across his stomach with a razor blade and on May 7, 1970 he took an overdose of tranquilizers The third time was the charm — he successfully hanged himself with a length of TV cord in his cell on California’s Death Row.

Edwards claimed to want a death sentence. Maybe he did — he attempted suicide twice during his trial. On March 30, 1970 he slashed a 14-inch cut across his stomach with a razor blade and on May 7, 1970 he took an overdose of tranquilizers The third time was the charm — he successfully hanged himself with a length of TV cord in his cell on California’s Death Row.

Edwards had always claimed six victims, never more; however, he is suspected in the murders of over 20 children between 1953 and 1970.

In 2006, a letter written by Edwards to his wife while he was on death row implicated him the 1957 disappearance of 8-year-old Tommy Bowman in the Arroyo Seco.

In 2011, the Santa Barbara Police Department took four teams of cadaver dogs to an area near a Goleta freeway overpass that was under renovation, looking for the remains of Ramona Price, a 7-year-old girl who disappeared in August 1961 — Mack Ray Edwards worked in the area during that time. Ramona wasn’t found, but the search for other victims of Edwards continues.

EPILOGUE

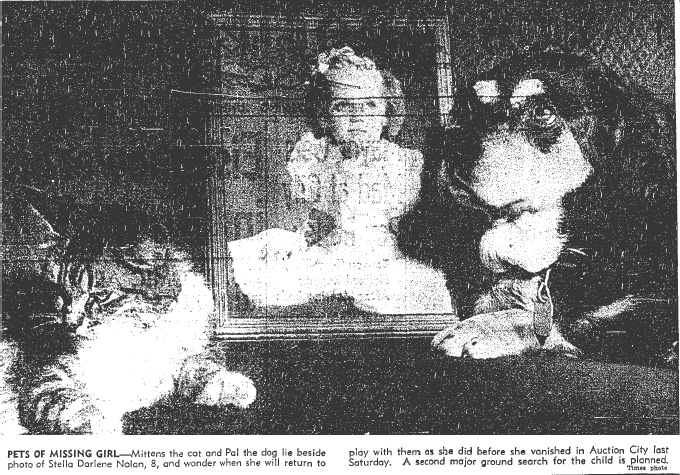

A little over 40 years following Mack Ray Edwards’ suicide I stumbled across Stella Darlene Nolan’s photograph in a Los Angeles Police Daily Bulletin as I was archiving documents from 1953. Something about Stella pulled me in and when I couldn’t find a cancellation for her missing notice in a subsequent Bulletin I followed up, and that’s when I discovered her entire story.

I shared everything I’d uncovered with the L.A. Police Museum’s Executive Director and he telephoned a detective he knows at Foothill Division. She told him she couldn’t discuss details of the case with him because she was assigned to the cold case! She’s seeking to solve many more murders and disappearances for which Edwards may have been responsible. The detective asked if we would send her a copy of the Daily Bulletin featuring Stella because she didn’t have one — it was an incredible feeling to be able to provide a small piece of information in an on-going investigation — my first cold case!

The Daily Bulletins aren’t merely artifacts to be cataloged and filed away; the impact of crime on victims and their families reaches across time. History lives.