I research a lot of heinous crimes for this blog. But, sometimes, I tumble down a research rabbit hole and find a character who captures my imagination; then I follow them through their time in Los Angeles.

Each person is a thread in the fabric of the city. Which is how I came to Babette Fontaine. I tugged on a random thread. I saw an article about her and was fascinated. I would describe Babette as an entrepreneur who shared qualities with other transplants to Los Angeles during the 1930s and 1940s. Growing up in rural America, and coming of age during the Great Depression, Babette had nothing handed to her.

Conservative perceptions of women at the time dictated the employment available to them. Even programs in President Roosevelt’s New Deal restricted women.

They could not join the Civilian Conservation Corps, and other programs put them into housekeeping jobs. I imagine, as the daughter of a Kentucky miner, Babette preferred not to be stuck in front of a stove or behind a desk. She became a burlesque performer instead and traveled the east coast for a few years as a dancer.

I love women who defy the conventions and expections of their time. Babette was a rebel.

By the 1930s, American burlesque shows were unrecognizable from their 16th century English literary antecedents. Burlesque during the Great Depression was a training ground for many great comedians and actors whose careers took off in mainstream movies and television during the 1940s and 1950s. Dozens of legendary strippers, Sally Rand, Gypsy Rose Lee, and my favorite, Betty “Ball of Fire” Rowland, began their careers in the 1930s.

Chicago police arrested Sally Rand four times in a single day at the 1933 World’s Fair for her fan dance. Feathers, bubbles, and snakes became props for inspired dancers. Other dancers came up with their own signature acts.

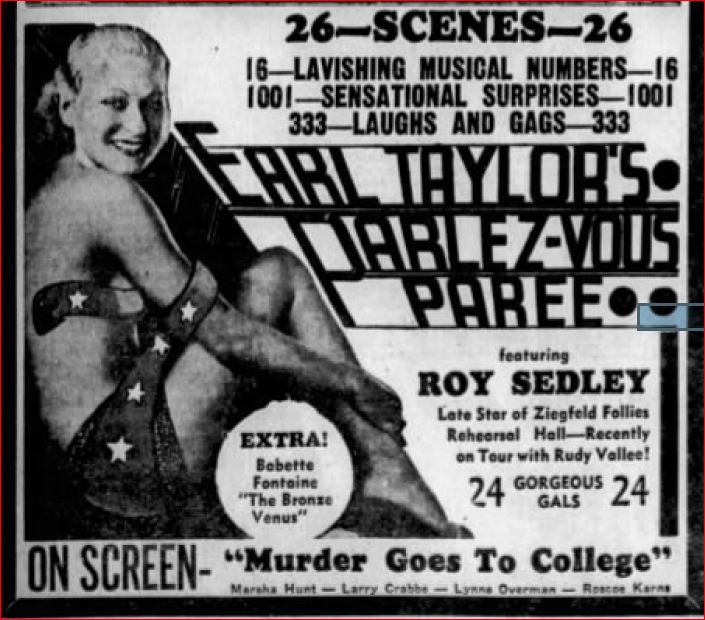

In 1936, Babette Fontaine painted her body bronze in imitation of a statue, and became known professionally as the Bronze Venus. The gimmick made her a featured player in Parlez Vous Paree, a burlesque revue produced by Earl Taylor. Babette wasn’t the only woman to claim the Bronze Venus moniker.

Beginning in the 1920s, black mega-star Josephine Baker was called Bronze Venus. Baker didn’t need paint to glow like a work of art. Others to advertise themselves as Bronze Venus were Ha Cha San, Bobby Lynn, Collette, and La Tonda.

Born to Burns and Maude Mccarty in rural Kentucky in 1916, Babette’s birth name may have been Dorothy. While Dorothy is an ideal name for a schoolteacher or housewife; Babette Fontaine looks better on a theater marquee.

The Parlez-Vous Paree show debuted in September 1936. It was a large production and featured scores of entertainers. They billed one as a stooge-like comedian. I wonder. Did he throw pies or chuckle nyuk, nyuk, nyuk?

A few months following the opening of the show, Babette’s name is prominently displayed in ads. The last mention of her is in November 1938.

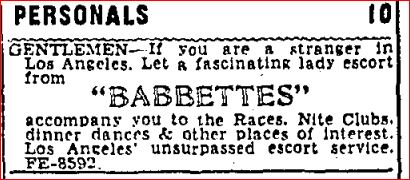

Between November 1938 and January 1940, Babette vanished from show business. Then, suddenly, she resurfaced in multiple newspapers in a wire service interview. They described her as the head of a Los Angeles escort service.

Asked, “What would you pay for a date with your favorite movie star?” Babette had a ready answer. She said that if, by some miracle, she could deliver the “oomph girl” Ann Sheridan as a dinner partner to a lonely gent on New Year’s Eve, she would expect to get $1500. To put that into perspective, the 2022 equivalent amount is $30,585.00! If the lonely gentlemen would accept a second-best companion, Babette said she would offer either Dorothy Lamour, Hedy Lamarr, or Claudette Colbert for $750.

Babette gave Greta Garbo a thumbs down as date material. Why? Because

she felt that men would be frightened of her.

What if a woman needed an escort? Babette named Tyrone Power as the perfect date. Clark Gable, not so much. She said, “I am afraid he is a little too much of the aggressive type.”

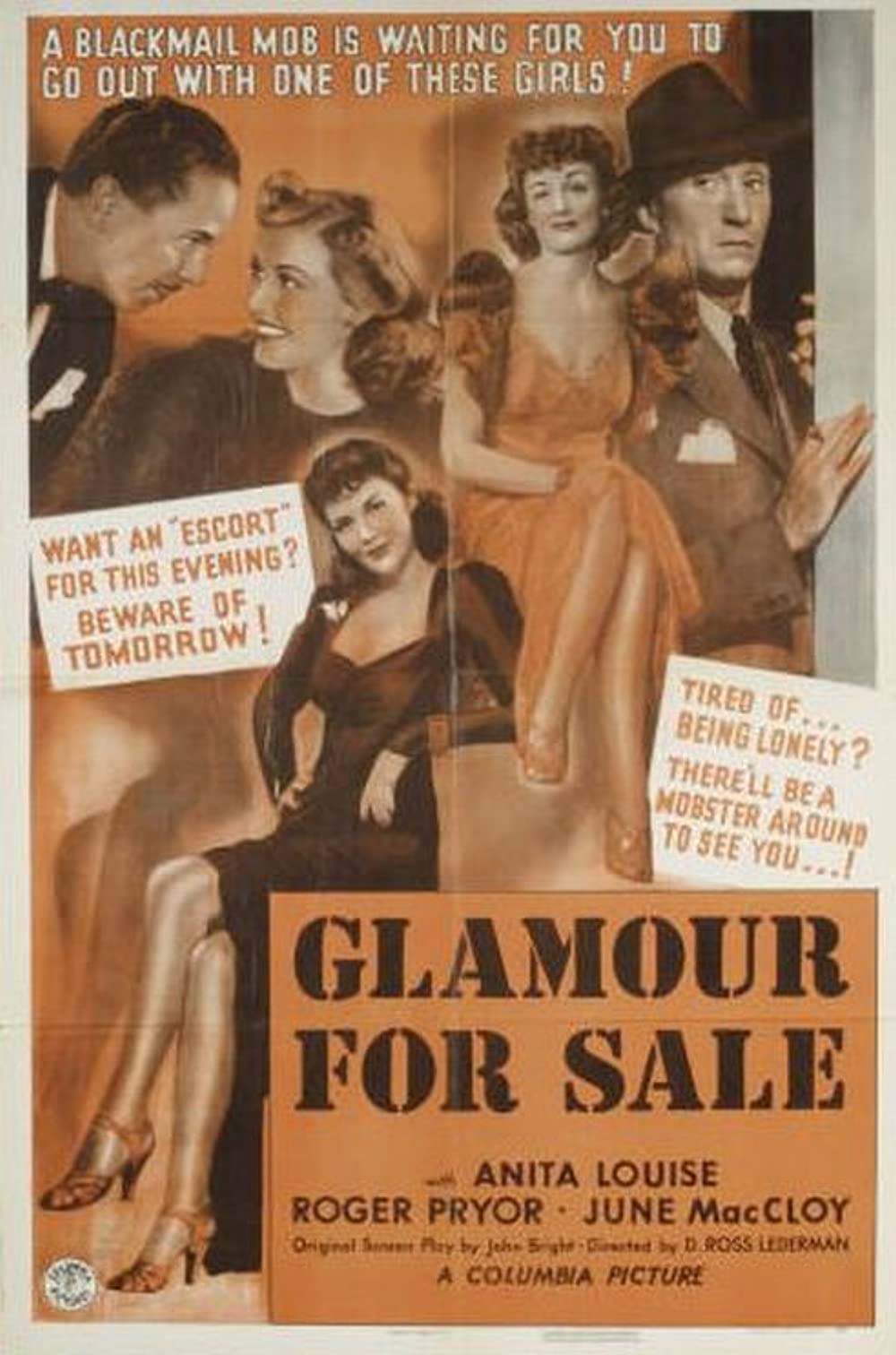

In April 1941, a few months after Babette rated various Hollywood stars as potential dates for hire, she appeared in newspapers again. Operating an escort agency out of 726 South Wilton Place, she filed an injunction against Columbia Pictures Corp. The company planned to produce a film called “Glamour for Sale”.

And why should the film concern Babette? Because it depicted the escort business as shady, specializing in extortion, blackmail and other criminal activities. Babette took umbrage. She said she had operated an escort bureau in Los Angeles for two years and had never engaged in anything illegal. She worried her reputation would suffer if they released the film.

Babette withdrew her suit in September when producers at Columbia said that they would also show legitimate escort businesses in “Glamour for Sale.”

In a move similar to Babette’s lawsuit, in late 1941, burlesque star Betty Rowland sued Samuel Goldwyn Productions for using her well-known stage name, “Ball of Fire” as the title for his upcoming film starring Barbara Stanwyck and Gary Cooper.

Several years ago, I asked Betty about her lawsuit. She winked and told me that the publicity was good for her and for the classic screwball comedy.

[Note: I’m pleased to report that as far as I know, as of this writing, Betty “Ball of Fire” Rowland is alive and well at 106! I hope she lives forever.]

Following the recall of Mayor Frank Shaw and the dismantling of his criminal empire in 1938, Los Angeles cracked down on vice. Regulations followed. One of the new regulations required escort bureaus to be licensed. Legislating morality is nigh impossible, but that never stopped a city, county, or a nation from trying.

A man seeking an escort sometimes expects more for his money than arm candy. If the woman is willing, they might make a deal without the agency’s knowledge. Of course, a crooked agency would encourage such arrangements and take a cut.

When Babette applied for a license in May 1941, she endured a grilling by the Police Commission. They wanted to know how much income tax she paid, what the girls charged and what she charged the girls.

According to Babette, she selected girls of good moral character, however, they were on “their own” after being introduced to the client. To me, that sounds like ass-covering 101. She said she charged the client $5. She then suggested to the client that he tip his date $5.

Babette claimed none of her girls ever had been arrested, and the only complaints she received about them came from police vice squad officers posing as clients. Sergeant John Stewart of the Central vice squad told a different story about one of Babette’s escorts. He and a few of his men operated an investigation out of the Biltmore and arrested one of the girls for “offering.”

Stewart, questioned about amounts paid to the escorts, said some demanded $50 from undercover investigators, others wanted $100 or more. A far cry from the five bucks Babette quoted.

Babette needed to prove she knew nothing of her escort offering undercover vice investigators a service not on the bureau’s official menu. She provided an alibi. She claimed she was out of town, or out of the office, when the girl was arrested. She played the sympathy card. The stress of the vice investigation caused her to suffer a breakdown. She fled to Dallas, Texas, for her nerves. Then she spent three days at the Hollywood Knickerbocker to further recuperate.

She produced receipts, which showed she was away when the girl was busted at the Biltmore. Babette also claimed a rival agency planted the girl to get her into trouble with the police.

The day after her license hearing, where she learned they postponed the renewal, Babette overdosed on sleeping pills in her car in a service station at Wilshire Boulevard and Detroit Street. She left a note, “Cards stacked—no use.” In her handbag she left a typewritten summary of her testimony to the Police Commission.

Babette claimed the police hounded her for not “playing nice,” and one vice cop in particular, who she nicknamed the “boogeyman”, followed her girls and clients, and prevented her from operating her business.

By July, Babette received the bad news. Her request for a license was denied. Babette’s attorney filed an appeal.

The drama kicked up a notch when, in February 1942, Babette claimed two men kidnapped and beat her.

She said two men followed her as she drove away from her home at 9038 Rosewood Avenue, Beverly Hills. Several blocks later, the men forced her car to the curb. A masked man got into her car and told her to follow his directions or “get a bullet in your back.”

She drove to 135th and San Pedro, where the men forced her from the car into a vacant lot. The thugs told her to “get out of town”, punched her on the jaw and knocked her out. When she revived, she had a gag in her mouth– her wrists and ankles tied. She struggled for an hour before freeing herself. Once freed, she walked into the street and flagged a passing motorist who took her to the Compton Police Station. Police reported Babette’s abductors had used her red lipstick to mark her forehead, cheeks and breasts with crosses. The significance of the red crosses is a mystery.

Babette had a flair for self-promotion. Was her kidnapping real? Without a description of her assailants, the police had nothing to investigate.

In early April, vice cops arrested Babette on morals charges in her home at 1769 S. Crescent Heights Boulevard. Arrested with her were Norma Clark and Harry Barker. Cops took the trio to Lincoln Heights Jail. They charged Babette with procuring and set her bail at $500. They charged Barker and Clark with resorting, and bail was set at $150 each.

Neighbors complained about suspicious goings-on at the bungalow and police staked it out for two nights before making the arrests.

Once her bail was posted, Babette made a beeline to her sister Colleen’s place at 2500 S. Hobart, where she was arrested while packing for a trip to Reno.

At first, Babette refused to appear in court. Then she changed her mind. She pleaded guilty to a misdemeanor procuring charge, and they immediately committed to jail for a medical exam (likely to screen for STDs) pending a probation hearing and sentencing. No word on how that turned out for her.

The Los Angeles Times offered a brief rundown of Babette’s escapades, beginning in 1941 and ending with her March 1943 arrest in Glendale after being found wandering along Brand Boulevard at 3:00 a.m. wearing only a white nightgown with gold trimmings.

This bizarre report ends the newspaper trail for Babette Fontaine—a fascinating and enterprising temporary Angeleno.

The last information I have for Babette is a marriage certificate. In Clark County, Washington, on January 28, 1946, Babette married Will Hayes—seventeen years her senior. Both gave as their address as the Broadway Hotel in Portland, Oregon.

Where they went and what they did as a couple following their marriage, I wish I knew. I hope Babette landed on her feet.