There is no such thing as a routine day in law enforcement. On Thanksgiving Day, 1923, a City of San Fernando motor officer, Nathan Oscar Longfellow, rode out to the scene of a reported riot on the 1300 block of Celis Drive.

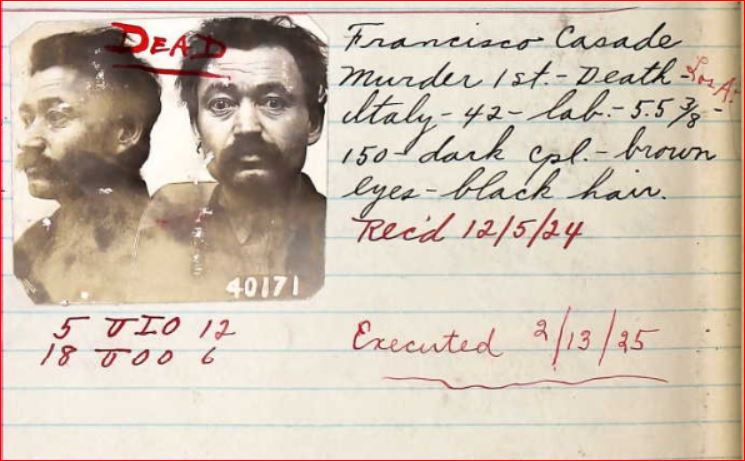

One hundred people filled the street, none of them too stuffed with turkey and pie to celebrate the holiday. There was no riot. The large gathering was peaceful except for one man, Francisco Casade, 45, a laborer who was drunk, loud, and creating a disturbance.

Longfellow rolled up on his motorcycle prepared to quell a riot. He found one unruly drunk.

Before a crowd of witnesses, Longfellow placed Casade under arrest for disturbing the peace and placed him in the sidecar of his motorcycle. As the motorcycle pulled away Casade attempted to escape.

Witnesses watched as Longfellow tried to restrain his prisoner. Casade produced an automatic pistol he had concealed under his vest. He fired three times. Longfellow dropped to the pavement.

The crowd, enraged by the shooting, fought Casade to the ground and held him until other officers arrived.

An ambulance transported Longfellow to the San Fernando Hospital where he died a few days later. The officer was a 21-year-old former clerk who had had joined the San Fernando Police Department 13-months earlier.

Fearing that citizens in the neighborhood would storm the local jail and lynch him, police took Casade to the Los Angeles County Jail and held him without bond.

The county grand jury heard testimony from J.W. Thompson, Chief of Police in San Fernando, Deputy Sheriff Charles Catlin, who investigated the case, and Mrs. G. Strathern, a witness to the shooting. The statements were enough indict Casade for Longfellow’s murder.

On January 11, 1924, the jury in the Francisco Casade trial informed Judge Reeve that they could not reach a verdict. The judge ordered them sequestered until the morning of the 12th. Maybe all the jury needed was an overnight incentive.

The jurors tried, but they squared off: six for hanging and six for life imprisonment. A conference between the District Attorney’s office and the judge resulted in a continuance until January 14.

Judge Reeve had no choice but to dismiss the jury after the foreman told him that six of the jurors held out for hanging and would not budge. They ordered a second trial to begin on January 18.

Casade’s public defender tried to use his client’s intoxication as a mitigating circumstance. He failed to convince his recalcitrant client to plead guilty and avoid the death penalty. Casade rolled the dice.

After two hours of deliberation, the jury returned a verdict of guilty for first degree murder. They sentenced Casade to hang.

Appeals are automatic in a death penalty case, and Casade’s snaked its way through the system to the State Supreme Court. In September 1924 the court upheld the sentence.

Holidays proved unlucky for Casade. He killed officer Longfellow on Thanksgiving Day 1923 and hanged for the crime on Valentine’s Day 1925.

On this day when we give thanks, let’s honor those people who have paid the ultimate price to keep us and those we love safe: law enforcement, firefighters, members of the military. They deserve our respect and support.

In memory of Nathan Oscar Longfellow, a young man who never got the chance to fulfill his dreams, the following poem by an unknown author.

“Policeman’s Prayer“

When I start my tour of duty

God,

Wherever crime may be,

as I walk the darkened streets alone,

Let me be close to thee.

Please give me understanding

with both the young and old.

Let me listen with attention until their story’s told.

Let me never make a judgment in a rash or callous way,

but let me hold my patience let each man have his say.

Lord if some dark and dreary night,

I must give my life,

Lord, with your everlasting love

protect my children and my wife.