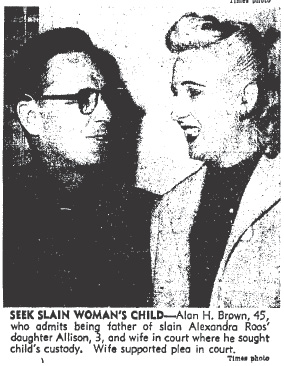

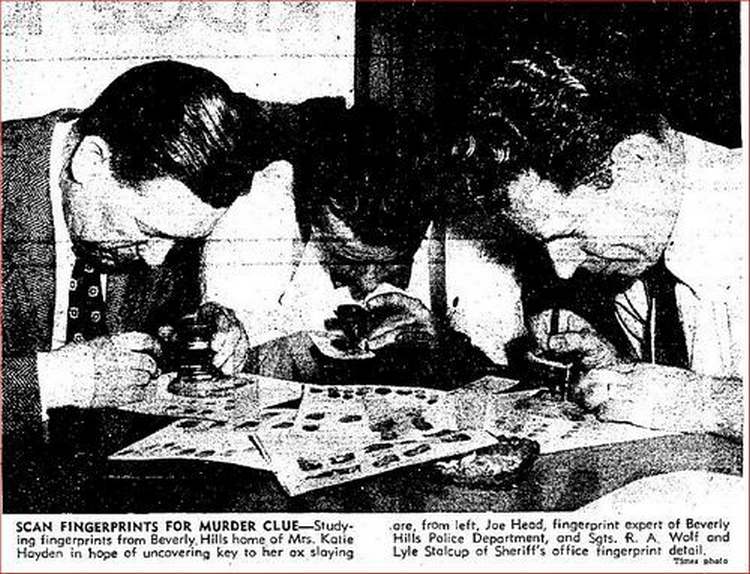

Their failure to solve the June 22, 1947 murder of Bugsy Siegel still rankled members of the Beverly Hills Police Department. None of them wanted to suffer the frustration of another high profile cold case. They were committed to solving Katie Hayden’s murder and they weren’t above asking for help. Many of the smaller Los Angeles county police departments, like Beverly Hills, were unaccustomed to conducting murder investigations so they enlisted the aid of the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department homicide bureau.

Rutherford Leon Bennett (R) and Nathaniel Smith (L). Photo courtesy of LAPL.

Despite his protestations of innocence, Rutherford Leon Bennett was a promising suspect. The Hayden’s had recently dismissed Rutherford as their cook when he failed to perform to their expectations. He said he phoned Samuel Hayden for a reference, but his call could have been interpreted as an attempt to extort money from his former boss for his firing. Rutherford was arrested and booked on suspicion of murder. His roommate, Nathaniel Smith, was taken into custody but released after an intense interrogation proved that he had no part in the crime.

Rutherford submitted to a lie detector test. He passed, but that wasn’t enough to satisfy the police. There are people who can defeat a polygraph – maybe Rutherford was one of them. Police weren’t about to kick him loose unless or until they had a better suspect.

Margaret and Rutherford. Photo courtesy LAPL.

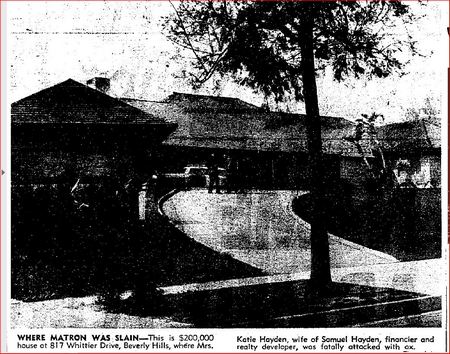

Peggy King, Rutherford’s replacement as the Hayden’s cook, was an obvious suspect because she was the only person in the house when Katie was murdered. But where was her motive? She had only been in the Hayden’s employ for three days.

Police learned that Peggy was also known as (Mrs.) Margaret Moore. Margaret was a relative newcomer to Los Angeles. She left her home in Houston, Texas in 1954 following a separation from her husband. Her father, Samuel Johnson, was a prominent figure in Houston’s Baptist church community. Nothing in Margaret’s background marked her as someone capable of hacking her employer to death with a hatchet. Still, police were obliged to subject her to the same scrutiny they gave Rutherford.

Detective Sergeant Ray Hopkinson of the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s homicide bureau assisted in the investigation. He said that one of Margaret’s male friends, with whom she had recently quarreled, had been located and was able to account for his whereabouts. One more suspect eliminated.

The police weren’t entirely satisfied with Margaret’s description of events. Since there was no one who could confirm or deny her story the police had to find another way to get at the truth. In her closet they found the dress that Margaret was wearing the day of the murder. It was spattered with what appeared to be blood. Even if the blood was Katie’s, it didn’t necessarily mean that Margaret was a killer.

Margaret’s alibi, that she had been vacuuming in another part of the house while Katie was being butchered, didn’t hold together when police realized that the killer would have had to pass Margaret to get to Katie.

Margaret had a date with the polygraph machine on February 11, 1955. Investigators hoped that the polygraph, the ultimate truth or dare device in a murder investigation, would reveal Margaret’s lies — if she was telling any. The former cook was questioned for over 90 minutes. The examiner concluded that Margaret was being deceptive in her answers.

Detectives used Margaret’s lies against her. It didn’t take long for her to break down and confess. But why had she done it?

Margaret. Photo courtesy LAPL.

According to Margaret the murder was the result of a heated argument she had with Katie about how to bone a roast. Katie was supervising Margaret in the kitchen and lost patience with her. In a fit of pique Katie snatched the small ax Margaret was using out of her hands and attempted to give her a demonstration.

“I had gotten the ax to cut the bone in the roast. During the argument Mrs. Hayden took the ax from me and tried to show me how to do it.” Margaret said.

“She (Katie) continued arguing with me and then I took the ax from her and struck her on the head. She didn’t fall after I struck her once and then I struck her again and again. I don’t know how many times I struck her after that. . .”

Margaret may have lost count of the blows it took to shatter Katie’s skull, but Dr. Newbarr, who conducted Katie’s autopsy, said that the sharp end of the ax had been used to inflict 20 to 30 cuts to her head and face. Then the butt end of the ax was used to fracture her lower left jaw and her upper left collarbone.

The vicious attack sent Katie to the kitchen floor in a bloody heap. “I stood over her for more than 10 minutes,” Margaret said. “I was dazed.”

She wasn’t too dazed to formulate a plan to escape detection. As Katie lay dying in a widening pool of blood, Margaret went upstairs and ransacked her employer’s room. “I opened all the drawers in the dressers and scattered clothing about the floor to make it appear that someone had broken in the house,” she told detectives.

While Margaret was yanking out dresser drawers and throwing clothing around Katie’s room, the telephone rang. The caller was one of Katie’s daughters, Rose Furstman. Margaret answered the phone and told her that someone had come in and killed her mother. Then she hung up. Rose lived at 1041 Hilts Avenue in West Los Angeles, barely two miles away from her parents’ home. It must have been an agonizing drive over to her parent’s home.

Margaret used the few minutes before Rose arrived to wipe her bloody hands clean with a dust rag. She tossed the rag and the ax into the kitchen sink, then she began to scream.

Margaret’s unholy wailing drew the attention of the half a dozen landscapers that were in the Hayden’s backyard installing a sprinkler system. When they got to the kitchen they found Margaret standing near Katie’s body. There was blood everywhere.

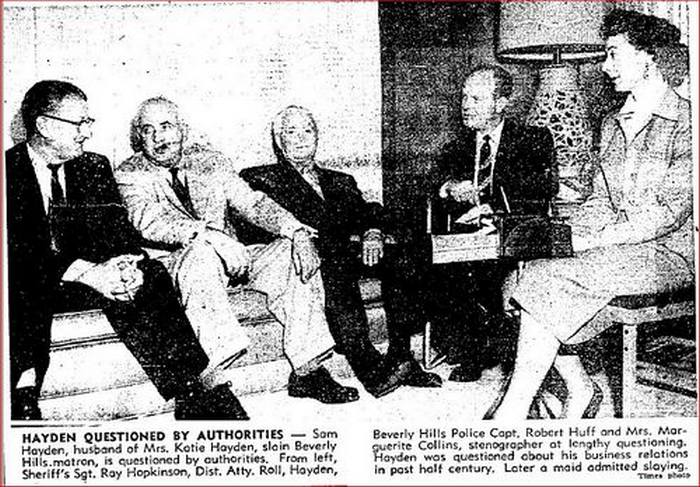

Margaret’s explanation for the murder was that her nerves were on edge because her common-law husband of two years had left her. Margaret’s two-year relationship was nothing compared to the 49 years that Samuel and Katie had spent together. The couple would have celebrated their 50th wedding anniversary in August.

Margaret comforted by her brother, Milton Johnson. Photo courtesy LAPL.

Roy King, the man Margaret called husband, showed up at the Beverly Hills Jail to comfort her. Her brother, Milton Johnson, also came to the jail to show support.

With Margaret’s confession in hand the cops breathed a sigh of relief. Their part was done. Now it was up to the courts to decide her fate.

There was talk of an insanity plea, so Dr. Marcus Crahan, County Jail psychiatrist, examined Margaret. After questioning her for 45 minutes Crahan said: “She is normal mentally.”

Margaret in tears. Photo courtesy LAPL.

With the confession and Dr. Crahan’s report against her, Margaret appeared before Judge Stanley Mosk and withdrew her earlier plea of innocent by reason of insanity and waived her right to a jury trial. It was a smart move, she likely would have fared much worse with a jury than she did with Judge Mosk. He heard the case without a jury and found Margaret guilty of second degree murder and sentenced to a term of from five years to life in state prison.

It wasn’t Katie who had screamed. Peggy King, the Hayden’s new housekeeper and cook, was responsible for the cries which shattered the quiet morning and drawn the landscapers and neighbors from several doors away to the gruesome scene.

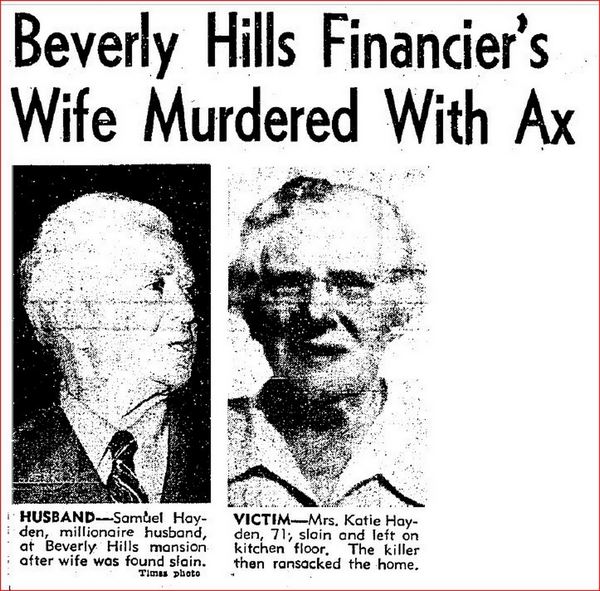

It wasn’t Katie who had screamed. Peggy King, the Hayden’s new housekeeper and cook, was responsible for the cries which shattered the quiet morning and drawn the landscapers and neighbors from several doors away to the gruesome scene. The police were called and within minutes Beverly Hills cops and an ambulance arrived. Katie was taken to Beverly Hills Emergency Hospital and then transferred to Cedars of Lebanon Hospital for surgery. She didn’t make it. Katie’s health had been poor for the last couple of years and she didn’t have to the strength to survive the vicious attack. Even a younger, healthier person would likely have succumbed. Dr. Frederick Newbarr, the Coroner’s chief autopsy surgeon, said that the beating Katie had suffered was the most vicious he had ever seen. The killer used the sharp end of the ax to inflict 20 to 30 cuts on her head and face; then used the butt end to fracture Katie’s left jaw and her upper left collarbone.

The police were called and within minutes Beverly Hills cops and an ambulance arrived. Katie was taken to Beverly Hills Emergency Hospital and then transferred to Cedars of Lebanon Hospital for surgery. She didn’t make it. Katie’s health had been poor for the last couple of years and she didn’t have to the strength to survive the vicious attack. Even a younger, healthier person would likely have succumbed. Dr. Frederick Newbarr, the Coroner’s chief autopsy surgeon, said that the beating Katie had suffered was the most vicious he had ever seen. The killer used the sharp end of the ax to inflict 20 to 30 cuts on her head and face; then used the butt end to fracture Katie’s left jaw and her upper left collarbone. Who could have wanted Katie dead? She wasn’t a high-risk victim – she was a Beverly Hills housewife.

Who could have wanted Katie dead? She wasn’t a high-risk victim – she was a Beverly Hills housewife.

Bennett’s alibi was straight forward. He told police that he was asleep at home when the murder was committed. But Bennett had supposedly telephoned Samuel following his dismissal and demanded two weeks’ severance pay. When the Hayden’s wouldn’t deliver did Bennett get mad enough to kill? Bennett denied that he had pressured the Haydens for money. He stated that his reason for calling was benign, he wanted permission to use them as a job reference.

Bennett’s alibi was straight forward. He told police that he was asleep at home when the murder was committed. But Bennett had supposedly telephoned Samuel following his dismissal and demanded two weeks’ severance pay. When the Hayden’s wouldn’t deliver did Bennett get mad enough to kill? Bennett denied that he had pressured the Haydens for money. He stated that his reason for calling was benign, he wanted permission to use them as a job reference. The Beverly Hills police didn’t want to risk another high-profile failure. They’d struck out on the Siegel murder in ’47. They arrested their only viable suspect in Katie’s murder, Rutherford Leon Bennett.

The Beverly Hills police didn’t want to risk another high-profile failure. They’d struck out on the Siegel murder in ’47. They arrested their only viable suspect in Katie’s murder, Rutherford Leon Bennett.