Los Angeles County Sheriffs had few clues in the murder of Alexandra “Xandra” Roos — but then most murder cases don’t come with a suspect and confession tied with a big red bow. The lack of evidence in the case meant that investigators had to rely on old-fashioned grunt work — and they began to question all of Xandra’s friends and acquaintances to see what they could shake loose. A logical place to begin was with Xandra’s ex-lover, and father of her child, Alan Brown.

Los Angeles County Sheriffs had few clues in the murder of Alexandra “Xandra” Roos — but then most murder cases don’t come with a suspect and confession tied with a big red bow. The lack of evidence in the case meant that investigators had to rely on old-fashioned grunt work — and they began to question all of Xandra’s friends and acquaintances to see what they could shake loose. A logical place to begin was with Xandra’s ex-lover, and father of her child, Alan Brown.

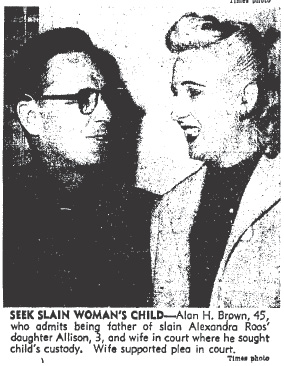

According to Brown he had become involved with Xandra in 1950 during a rough patch in his marriage. After giving birth to a little girl, Xandra threatened him with a paternity suit unless he agreed to support the child. Brown decided to pay up and he had been sending Xandra $10 weekly support through the City Attorney’s office for a couple of years.

Homicide investigators weren’t completely satisfied with Brown’s statement, it seemed too neat, so they pushed him a little harder.

During his interrogation, Alan revealed that he’d taken Xandra out for at least four months before she had finally consented to have sex with him. He also confessed to the cops that he and the dead woman had continued their affair, off and on, until there was an ugly confrontation between Xandra and his wife, Viola.

Xandra had been pressing Alan for child support, and to make sure he knew that she was serious she turned up at the house he shared with Viola. The visit didn’t go well. Viola called Xandra a bum, and Xandra responded by calling Viola a slut. It was a nightmare for Alan who had been led woefully astray by his penis. He was just an average Joe in his 40s looking to bed a sweet young thing while he and his wife were on the outs — but his entanglement with Xandra had nearly cost him his marriage and had briefly made him a murder suspect. There’s a lesson in there somewhere.

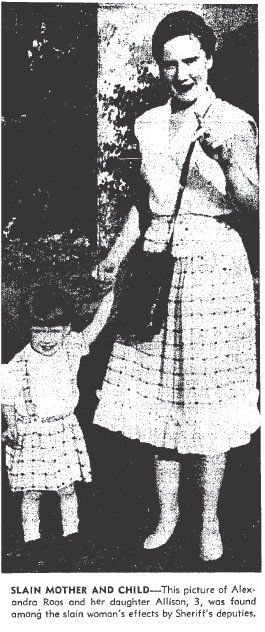

While detectives were grilling the people who had played a part in Xandra’s life, the fate of her daughter, Allison, was getting more complicated by the minute. Xandra’s will made it clear that she didn’t want her mother and step-father, Frieda and Hugh Schmidt of Tukahoe, NY, to have any role in her daughter’s upbringing. Xandra had stipulated that the Schmidt’s should:

“…be not designed or appointed guardian of the person or property of my daughter.”

Mrs. Hannah Frank of the Bronx, N.Y., who had once taken care of Allison, was named

as the girl’s guardian. But Alan’s wife Viola declared that not only had she forgiven her husband for the affair she was eager to bring his child with Xandra into their home. She declared:

“We want to make a real home for Allison and give her the love parents — something she has never known.”

The battle for guardianship of Allison raged on while services for her mother were held in the chapel of the McGlynn Mortuary. Among the small group of mourners was Xandra’s mother, who flung herself over the flower-decked coffin of her murdered daughter. She sobbed uncontrollably for a few minutes before being led away.

Xandra’s personal life and finances were so complex that detectives despaired of ever untangling the mystery of her murder. They didn’t even have a clear motive for the killing until they learned of Xandra’s relationship with Frank and Anita Meloche.

Xandra had first met Anita and Frank in July of 1954 when she answered their rental ad. The situation at first seemed to be mutually beneficial — Anita cared for Allison while Xandra worked, which meant that the Meloches collected both rent and money for babysitting. Then in August or September Xandra approached Anita with an interesting proposition. Xandra offered to loan the couple enough money to purchase a bigger home — the only attached string was that Anita would continue to care for Allison.

It sounded like a good deal, so Anita and Frank went for it. Xandra loaned them five thousand dollars (equivalent to $43,000 in current U.S. dollars) which they used to buy a home on the 4200 block of Perlita Avenue in Glendale.

Xandra moved with Allison to a nearby apartment, and then began to make plans to build a second house behind the home that Anita and Frank had purchased. The structure that Xandra had in mind turned out to be too large for the lot, so it was back to square one. Xandra then came up with the idea to purchase the house next door, but all the wheeling and dealing was getting to be too much for Anita.

Xandra moved with Allison to a nearby apartment, and then began to make plans to build a second house behind the home that Anita and Frank had purchased. The structure that Xandra had in mind turned out to be too large for the lot, so it was back to square one. Xandra then came up with the idea to purchase the house next door, but all the wheeling and dealing was getting to be too much for Anita.

Xandra had one last suggestion, and it seemed bizarre to Anita. Xandra said:

“What do you want to stay with Frank for? I can do so much for you, Anita, if you would only let me. Leave Frank and we’ll go somewhere.”

Anita was being run ragged between caring for her own children, babysitting for Allison, and running errands for Xandra. On top of everything, Xandra wouldn’t stop pressuring her to leave Frank, something Anita refused to do.

Once detectives discovered that Xandra had made a sizable personal loan to the Meloches, they had a thread to tug on. Money is a powerful motive — but would it lead them to a killer?

One of my favorite Sheriff’s investigators, Det. Sgt. Ned Lovretovich, interviewed Frank and he collapsed, sobbing — then he spilled the whole awful story. (For more on Ned see: Thugs With Spoons and Death Doesn’t Sleep )

Frank said that at about 6:30 p.m. on the evening of January 7, 1955, Anita asked him to go to the store for her. The errand shouldn’t have taken more than 30 minutes — but he was gone for over four hours.

When he finally turned up, Anita asked him:

“Where were you so long?”

Frank replied:

“I just got rid of her”.

Anita fainted.

Once she had regained her senses, Frank confessed to Anita — and he told the same version of events to homicide investigators.

Frank had met Xandra at a streetcar stop at the intersection of Glendale Blvd. and Brunswick Ave. He wanted to persuade Xandra to stop making demands on Anita and to leave them alone. He said:

“She (Xandra) didn’t like me. She kept pestering my wife to take our children and come and live with her. She was making a slave out of my wife. I decided to tell her to stay away from us.”

Xandra got into Frank’s car and their chat quickly turned into a heated argument. Frank said that Xandra taunted him about his manhood, or lack thereof, and then slapped him hard across the face. Frank pulled his car to the curb near the intersection of Hart St. and Sepulveda in Van Nuys, and then he snapped. He said that he grabbed Xandra around the neck and throttled her — minutes later she slipped to the floor of the car, dead.

Frank drove her body out near the beach where it was discovered a couple of weeks later.

Frank said that he couldn’t take any more of Xandra’s abuse, and that he had felt an explosion in his brain which compelled him to grab the woman and choke the life out of her. Evidently Frank was no stranger to brain explosions. He had been discharged from the Navy during WWII after being diagnosed as a “constitutional psychopath” — a condition described in 1926 in The Journal of the American Medical Association as:

“…a generic term to include the six classes of constitutional psychopathic states noted in the nomenclature; criminalism, emotional instability, inadequate personality, paranoid personality, pathologic liar and sexual psychopathy.”

Frank Meloche was found guilty of murder and sentenced to from one to ten years in prison.

Despite Xandra’s will custody of her daughter, Allison, was awarded to Frieda.

Judge Wolfson said that he had disregarded Xandra’s wishes because:

“…sometimes we have an unconscious hate for those we know we have wronged.”

It wasn’t made clear in what way Xandra may have wronged her mother and stepfather.

Alan and Viola Brown had filed a petition for custody of Allison, but the judge denied it because he thought they seemed a little too interested in the girl’s inheritance.

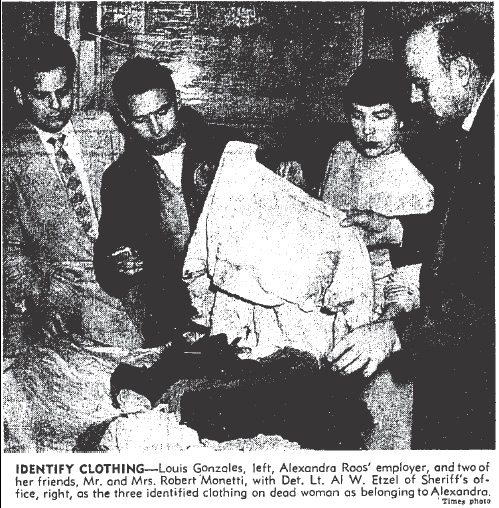

The only good news in connection with the Roos case was that the Sheriff’s investigators, who had managed to solve the case despite the initial lack of evidence or clues, were recognized for their accomplishment. Cited were: Lt. Al Etzel, commander of the Sheriff’s homicide detail, and Det. Sgts. Harry Andre, Claude Everley, Jack Lawton, Norman Peterson, Ned Lovretovich, Hubert A. Waldrip, Norman Hamilton, Ray Hopkinson and Lyle Stalcup.

Unfortunately even a successful investigation couldn’t bring Xandra back to life. Alexandra Roos was a fascinating and complex woman; she was a free spirit with a strong will and sense of independence unusual for her time; but she still had a long way to go — how sad that she never got the chance to realize her potential.