February 9, 1955

Beverly Hills, California

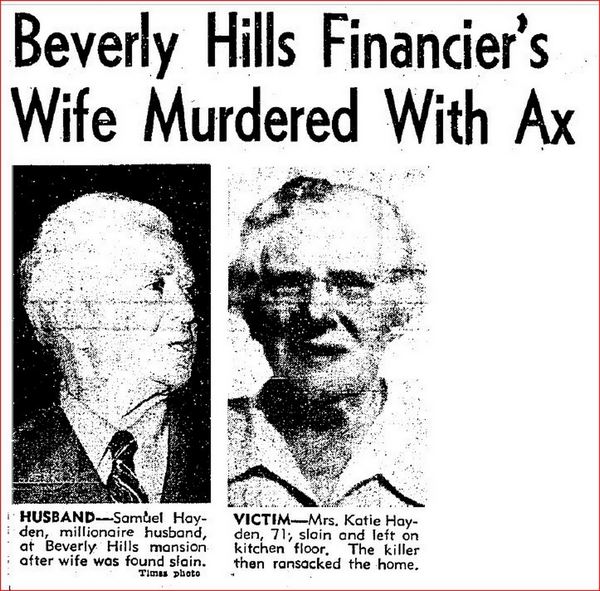

Half a dozen landscapers were hard at work installing a sprinkler system on the grounds of Samuel Hayden’s Beverly Hills estate at 817 North Whittier Street when they were startled by screams coming from inside the home. Dropping their tools as they ran, the men followed the bloodcurdling shrieks to the back entrance to the kitchen. The first man in door must have been horrified. 71-year-old Katie Hayden lay in a widening pool of blood. She had been beaten so badly she was barely recognizable. In the sink was a bloody rag and a small ax.

It wasn’t Katie who had screamed. Peggy King, the Hayden’s new housekeeper and cook, was responsible for the cries which shattered the quiet morning and drawn the landscapers and neighbors from several doors away to the gruesome scene.

It wasn’t Katie who had screamed. Peggy King, the Hayden’s new housekeeper and cook, was responsible for the cries which shattered the quiet morning and drawn the landscapers and neighbors from several doors away to the gruesome scene.

The police were called and within minutes Beverly Hills cops and an ambulance arrived. Katie was taken to Beverly Hills Emergency Hospital and then transferred to Cedars of Lebanon Hospital for surgery. She didn’t make it. Katie’s health had been poor for the last couple of years and she didn’t have to the strength to survive the vicious attack. Even a younger, healthier person would likely have succumbed. Dr. Frederick Newbarr, the Coroner’s chief autopsy surgeon, said that the beating Katie had suffered was the most vicious he had ever seen. The killer used the sharp end of the ax to inflict 20 to 30 cuts on her head and face; then used the butt end to fracture Katie’s left jaw and her upper left collarbone.

The police were called and within minutes Beverly Hills cops and an ambulance arrived. Katie was taken to Beverly Hills Emergency Hospital and then transferred to Cedars of Lebanon Hospital for surgery. She didn’t make it. Katie’s health had been poor for the last couple of years and she didn’t have to the strength to survive the vicious attack. Even a younger, healthier person would likely have succumbed. Dr. Frederick Newbarr, the Coroner’s chief autopsy surgeon, said that the beating Katie had suffered was the most vicious he had ever seen. The killer used the sharp end of the ax to inflict 20 to 30 cuts on her head and face; then used the butt end to fracture Katie’s left jaw and her upper left collarbone.

Who could have wanted Katie dead? She wasn’t a high-risk victim – she was a Beverly Hills housewife.

Who could have wanted Katie dead? She wasn’t a high-risk victim – she was a Beverly Hills housewife.

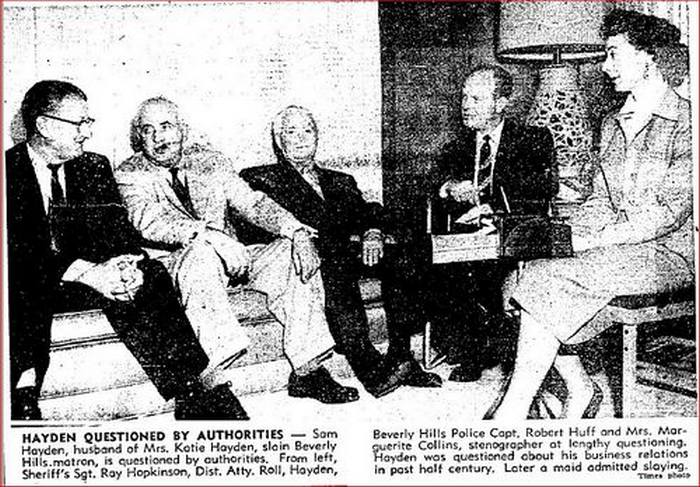

Investigators dug into the Hayden’s background. Did Samuel, who had made a fortune as a real estate developer, have enemies who hated him enough to get to him through is family?

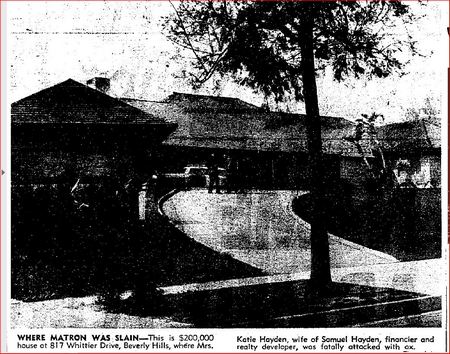

The Haydens had relocated to Los Angeles from Chicago in the mid-1940s and moved to Beverly Hills. They began construction on the Whittier Street home during the summer of 1954 and were occupying it by December. The $200,000 [equivalent to $1.8 million dollars in today’s currency] estate was their dream home. It was also less than 300 feet away from 810 N. Linden Drive where mobster Benjamin “Bugsy” Siegel had been shot to death in the home’s living room in June 1947.

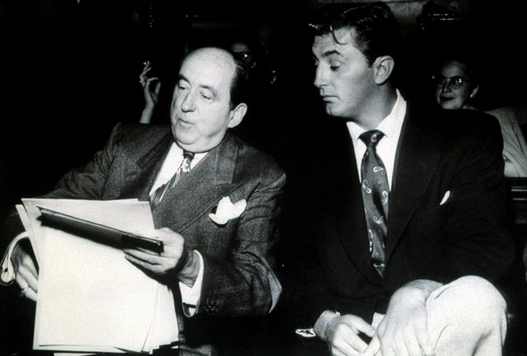

Bugsy Siegel with his attorney Jerry Geisler. [Photo courtesy of LAPL.]

Siegel was a mobster and the Hayden’s were from Chicago, a city with a long history of mob activity. Was there a connection?

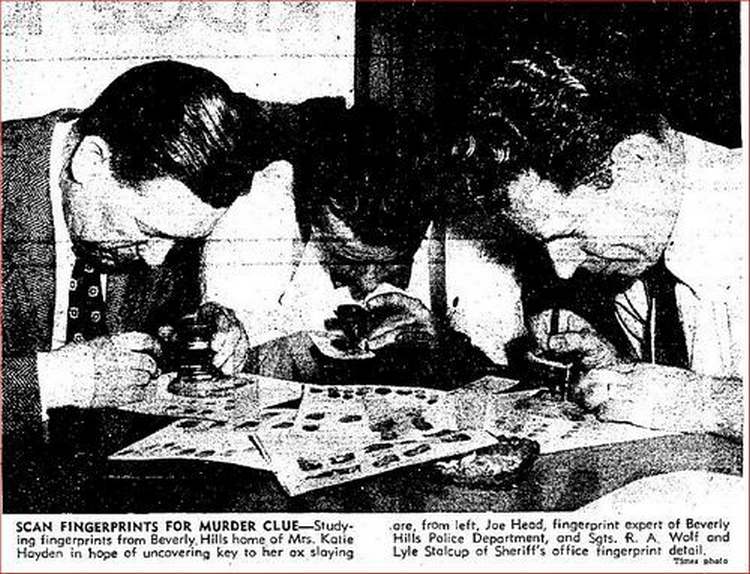

The last thing the city wanted was another unsolved high-profile murder case. Because the house had been under construction and workmen had been in and out, the detectives had at least 50 people to interview. The master bedroom had been ransacked, maybe the murder was a burglary gone wrong. What if someone knew that Katie had been diagnosed with cancer and assumed she had narcotics on hand? Pharmaceutical grade drugs would be a powerful inducement for someone.

Police didn’t find anything to corroborate mob involvement, and the interviews they had conducted in the early hours of the investigation hadn’t led to any blinding insights. Even so, they turned up an interesting suspect. Three weeks prior to the murder 39-year-old Rutherford Leon Bennett had been dismissed from the Hayden’s employ when he failed to meet their standards for a cook. Since Bennett claimed his primary skill was millinery, specifically creating hats for wealthy matrons, his culinary skills may have been lacking.

Bennett’s alibi was straight forward. He told police that he was asleep at home when the murder was committed. But Bennett had supposedly telephoned Samuel following his dismissal and demanded two weeks’ severance pay. When the Hayden’s wouldn’t deliver did Bennett get mad enough to kill? Bennett denied that he had pressured the Haydens for money. He stated that his reason for calling was benign, he wanted permission to use them as a job reference.

Bennett’s alibi was straight forward. He told police that he was asleep at home when the murder was committed. But Bennett had supposedly telephoned Samuel following his dismissal and demanded two weeks’ severance pay. When the Hayden’s wouldn’t deliver did Bennett get mad enough to kill? Bennett denied that he had pressured the Haydens for money. He stated that his reason for calling was benign, he wanted permission to use them as a job reference.

Bennett’s roommate, 24-year-old Nathaniel Smith, verified Bennett’s alibi. Smith said that he and Bennett had been out until 5 a.m. on the morning of the murder and that when they arrived home both had immediately gone to bed. Another point in Bennett’s favor is that he didn’t own a car so getting to Beverly Hills from his home at 1403 West 39th Street would have been a challenge. He could have used Smith’s car, but a police search of the vehicle revealed no bloodstains. Bennett’s clothing was also free of bloodstains.

The Beverly Hills police didn’t want to risk another high-profile failure. They’d struck out on the Siegel murder in ’47. They arrested their only viable suspect in Katie’s murder, Rutherford Leon Bennett.

The Beverly Hills police didn’t want to risk another high-profile failure. They’d struck out on the Siegel murder in ’47. They arrested their only viable suspect in Katie’s murder, Rutherford Leon Bennett.

Bennett, Smith and the Hayden’s maid of three days, Peggy King, were each scheduled to take a lie detector test. Cops hoped for a revelation.

NEXT TIME: False alibis and new clues.

Less than a week into the investigation police discovered that Earle was the victim of extortion — a blackmail scheme run by a man and woman. The woman had allegedly seduced Earle then told him it would cost him big time for her to keep her mouth shut about their affair.

Less than a week into the investigation police discovered that Earle was the victim of extortion — a blackmail scheme run by a man and woman. The woman had allegedly seduced Earle then told him it would cost him big time for her to keep her mouth shut about their affair.