Blanche Remington — Earle Remington’s sister.

Blanche Remington and her attorney Samuel H. French paid the District Attorney’s office a visit on April 28, 1923. Blanche was terrified. She told District Attorney Thomas Woolwine and Deputy District Attorney Asa Keyes that she was being shadowed by as many as four persons. She had first noticed her stalkers trailing her in an automobile immediately following Earle’s murder. Since then she could feel strange eyes on her no matter where she was.

During her meeting with Woolwine and Keyes, Blanche revealed what she knew of her brother’s finances in the few years prior to his death. According to Blanche, she had lent Earle money for various enterprises for many years. Unfortunately, Blanche was familiar with Earle’s legal business dealings, but knew nothing about his bootlegging side line. Woolwine told reporters, “Miss Remington arranged the conference through her attorney. She believed that she might be able to help us in our investigation, but she has told me nothing that can be used in apprehending Remington’s slayer.”

Was Woolwine telling the truth about Blanche’s ignorance of her brother’s bootlegging scheme? Or was he equivocating in the hope that it would prevent her from being targeted by people who might fear her disclosures? Reporters turned up at Blanche’s home at 1365 ½ West Twentieth Street in attempt to get more information, but the frightened woman refused to divulge any details.

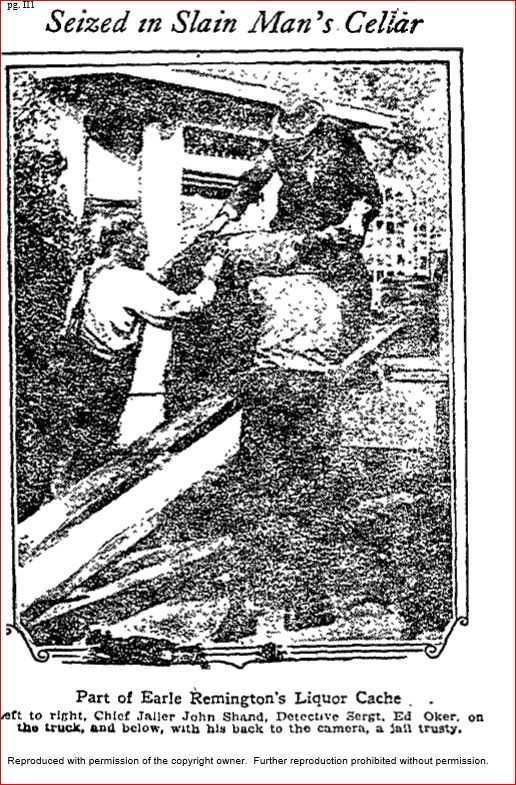

Three weeks following Blanche’s meeting with the District Attorney, prohibition agents and the Long Beach Police raided a major bootlegging outfit. Eight men were arrested, two of whom were millionaires thanks to the Eighteenth Amendment. The raid resulted in the seizure of 160 cases of whiskey, two trucks, four automobiles and a Japanese fishing launch. The authorities thought they could make a connection between the bootleggers and Earle’s murder. Earle had allegedly conducted business with Claude V. Dudrey, one of the men being held on charges stemming from the raid. Claude didn’t deny his association with Earle. He admitted under questioning that he had attempted to get the lease on a building Earle was preparing to vacate. He also admitted to having sold seven cases of booze to Earle. But he adamantly denied any involvement in the murder.

There were reports of high-jacking, shootings and even piracy on the high seas linked to several members of the bootlegging ring but there was nothing to suggest that any of the men had been involved in Earle’s murder.

On April 30, 1923, after months of frustration and dead ends, the Los Angeles Times reported that a young woman, who remained nameless in the report, came forward with a story that everyone hoped would resolve the case. Unfortunately, the woman had not approached police with her tale. She had allegedly confessed to local defense attorney S.S. Hahn. Hahn merely played the messenger. He met with Assistant District Attorney Asa Keyes and repeated what he had been told.

According to Hahn, the woman (whom Hahn described as an attractive 28-year-old brunette) said she and Earle had been lovers for more than eighteen months, but his interest in her began to wane. She tried unsuccessfully to hold on to him. The woman told Hahn: “I loved Remington and expected him to marry me. I first began to share his love more than a year and a half ago. I had been married. I knew he was married, but he promised that he would obtain a divorce and marry me. For a year we were happy. He and I lived together for a time at the beach at Venice. Then gradually his love seemed to cool. He missed his appointments with me and I say less and Less of him.”

According to Hahn, the woman (whom Hahn described as an attractive 28-year-old brunette) said she and Earle had been lovers for more than eighteen months, but his interest in her began to wane. She tried unsuccessfully to hold on to him. The woman told Hahn: “I loved Remington and expected him to marry me. I first began to share his love more than a year and a half ago. I had been married. I knew he was married, but he promised that he would obtain a divorce and marry me. For a year we were happy. He and I lived together for a time at the beach at Venice. Then gradually his love seemed to cool. He missed his appointments with me and I say less and Less of him.”

There was more:

“At first I suspected and then I knew that there were other women in his life. It became more and more difficult for me to see him and finally I realized that he was out of my life. I wanted to talk to him, but was unable to meet him. Time after time I sought an interview with him at his office without success. Then, on the day of the shooting I trailed him. I saw him meet the other woman. I followed them. They had dinner together in a restaurant. I waited outside while they dined and followed them to the Athletic Club (Los Angeles Athletic Club), where I lost track of them. That day I carried with me a bottle of acid with which I planned to forever disfigure both of them. After losing trace of them I got in touch with a man I knew I could trust and asked him to help me. He brought another man with him. With them I drove to the Remington home and waited for Earle. I wanted to talk with him.”

According to the mystery woman she never got the chance to talk to Earle again. She said she waited in the car for her two men friends to bring Earle to her. She saw Earle drive up and then there was a scuffle. The evening quiet was shattered by two gunshots and the woman’s screams.

From the murder scene the woman said she was driven by the killers to her aunt’s home where she lived for the first few weeks following the murder. The woman confessed details of Earle’s murder to her aunt. She didn’t share details of the murder with her friends, but everyone she knew shielded and aided her. But, if S.S. Hahn was to be believed, the woman was so conscience stricken that she was ultimately compelled to seek the attorney’s counsel.

S.S. Hahn told reporters, “The woman came to me as a client and said she was wanted for the slaying of Earle Remington. She said she would disclose the details of the murder if the District Attorney’s office would assure her she would be allowed liberty on bail pending the trial. She was nervous, hysterical and exhausted.”

The D.A. wasn’t prepared to make the deal and S.S. Hahn refused to name his client if they couldn’t reach an agreement.

The Remington case stalled again in early May. LAPD Captain Home said, “we are no nearer a solution of the mystery than we were two months ago.”

Two months turned into two years, then twenty. It has now been nearly 95 years since Earle was murdered in the driveway of his home. Yet, there was a brief glimmer of hope when a WWI veteran, Lawrence Aber, confessed. His reason? He said he was angry at Earle for selling liquor to veterans. It didn’t take long for the police to realize that Aber had lied. He wasn’t being malicious, he suffered from severe mental issues and he was in a hospital at the time of the slaying.

Two months turned into two years, then twenty. It has now been nearly 95 years since Earle was murdered in the driveway of his home. Yet, there was a brief glimmer of hope when a WWI veteran, Lawrence Aber, confessed. His reason? He said he was angry at Earle for selling liquor to veterans. It didn’t take long for the police to realize that Aber had lied. He wasn’t being malicious, he suffered from severe mental issues and he was in a hospital at the time of the slaying.

For several years following her husband’s death, Peggy Remington suffered a series of tragedies. She lost three brothers to various ailments including paralysis and Bright’s Disease. And most of her money vanished due to “sharp practices of asserted friends.” She was undeterred. “It means I am going to work; I am going to be hostess of a country club at Rye, N.Y.” She smiled at reporters and said, “Oh, I’ll get along.”

Despite the dozens of suspects identified early in the investigation, detectives never got the break they needed to catch the killer(s).

It is always hard for me to reconcile myself to the fact that someone got away with murder. In this case there were so many suspects it was dizzying.

So, I’m curious. Who do you think murdered Earle? Bootleggers? Former business partners? An ex-lover? Feel free to weigh in.

Aimee Torriani’s self-proclaimed psychic abilities were underwhelming. She put forward the same theory that Earle’s brother-in-law had suggested — that the killer was a veteran of the world war. According to Aimee the mystery vet’s motive was simple, he respected Peggy Remington for her work with veterans and felt her husband was doing her dirt with his constant string of affairs.

Aimee Torriani’s self-proclaimed psychic abilities were underwhelming. She put forward the same theory that Earle’s brother-in-law had suggested — that the killer was a veteran of the world war. According to Aimee the mystery vet’s motive was simple, he respected Peggy Remington for her work with veterans and felt her husband was doing her dirt with his constant string of affairs.

Less than a week into the investigation police discovered that Earle was the victim of extortion — a blackmail scheme run by a man and woman. The woman had allegedly seduced Earle then told him it would cost him big time for her to keep her mouth shut about their affair.

Less than a week into the investigation police discovered that Earle was the victim of extortion — a blackmail scheme run by a man and woman. The woman had allegedly seduced Earle then told him it would cost him big time for her to keep her mouth shut about their affair.