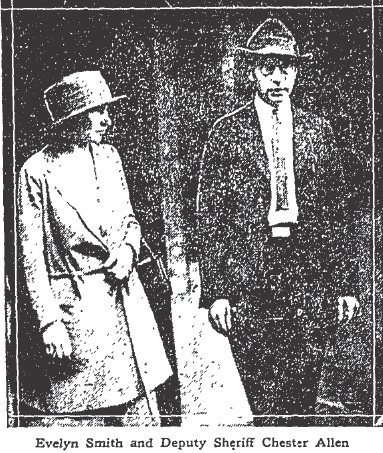

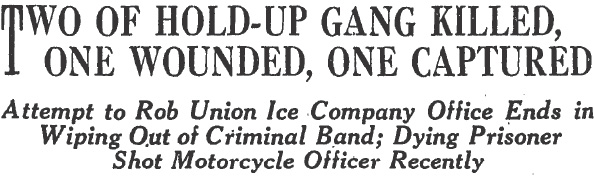

Not long after the bloody shootout between the Burton gang and Sheriff’s deputies at the Union Ice Company, in which all of the bandits except J.W. Gilkye were killed, deputies found Edward Burton’s girlfriend. Investigators located the young woman in a room at the Superior Hotel. She was taken into custody under her alias, Mary Dayke, but quickly revealed her given name, Evelyn Smith.

Smith, like Burton, was from Chicago. Questioned by Chief of Criminal Investigation, A.L. Manning and Deputy Sheriff Chester Allen, Smith said that she had no idea what Burton was up to or why he had left Chicago for Los Angeles. “I know nothing of Burton’s crimes. I did not realize he was leading a life of crime until he was arrested in the raid. Even then I did not believe he was the man who shot the motor officer.

Smith continued: “I came out from Chicago last May to join Burton. Be he soon lost interest in me. He told me I was not the kind of a girl to stick with him. Last Tuesday afternoon, only a few hours before he was killed, he accused me of being too inquisitive. He said I asked too many questions, told me to mind my own business. And then he beat me severely.”

Sheriff’s investigators asked Smith about the two one-way train tickets to Chicago that were found in Burton’s coat pocket, but again she claimed to know nothing. Evidently, Burton had a new woman in his life; a blonde with bobbed hair who had accompanied the bandit gang on a number of robberies. Smith said Burton planned to “ditch” her for his new squeeze and leave Smith in Los Angeles to fend for herself.

Sheriff’s deputies conducted raids at several locations in an attempt to round up other members of the gang. The lawmen came up empty. The gunsels, aware that the deputies wielded sawed-off shotguns and were prepared to do battle, had fled the city for parts east.

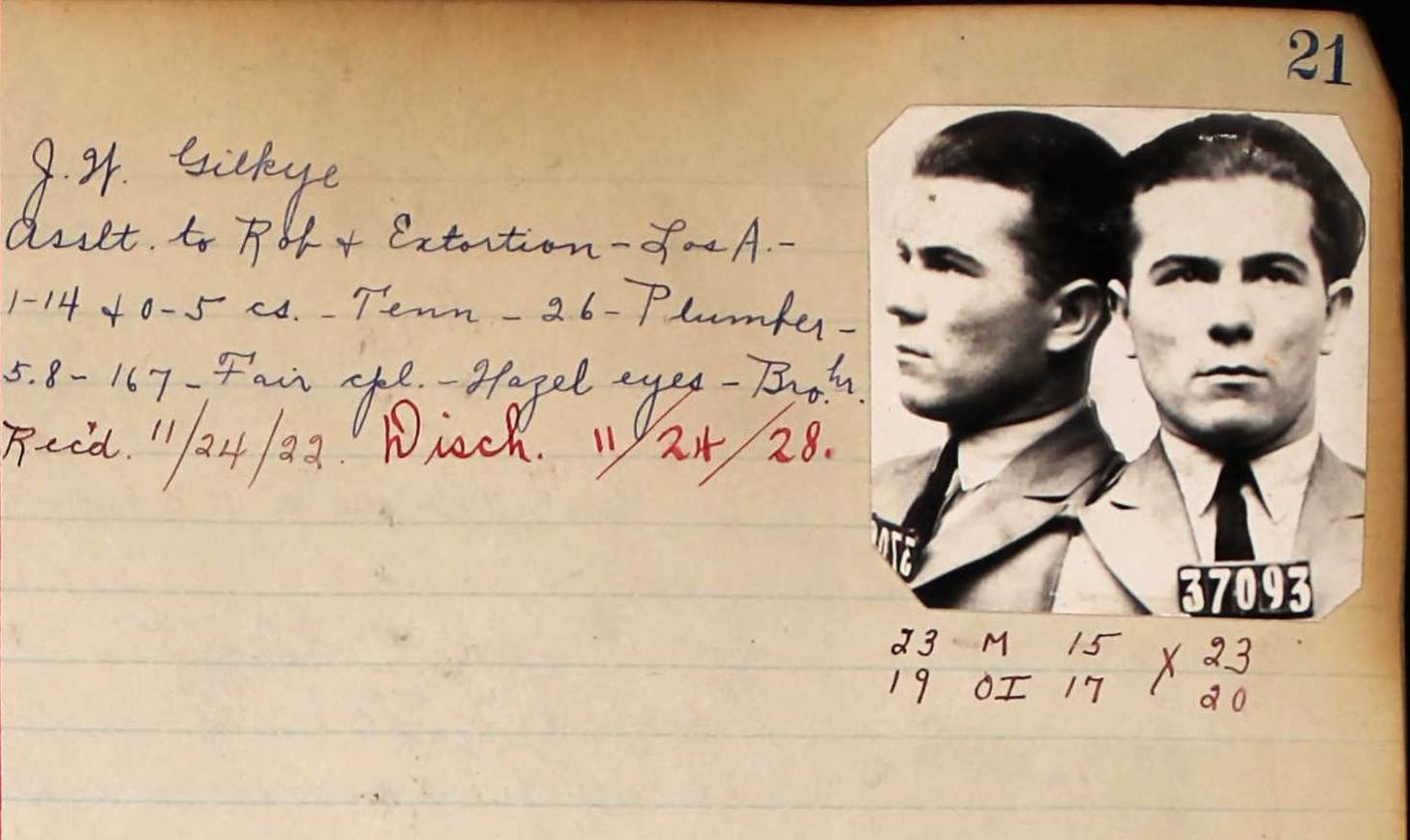

Only J.W. Gilkye, the lone bandit to survive, was left to answer for the crimes he and his fellow thugs had perpetrated. Gilkye survived only because he had dropped his weapon and refused to fight when deputies drew down on him at the ice company.

During questioning, Gilkye said: “You got enough on me without me telling you more.” And then he proceeded to tell Chief Deputy Manning a lot more. Like many crooks Gilkye loved the sound of his own voice and couldn’t resist crowing about his criminal accomplishments and playing the tough guy. “I may get hooked for a long time up the road, but I ain’t through yet. We were double-crossed, we were, by one of our own gang. But I’ll get him if it takes all my life. He double-crossed us and caused three of my best pals to get killed. But they were nervy–had the goods.” The “goods” can’t do much for you when you’re dead.

Gilkye wasn’t as nervy as his pals had been, so he lived to tell the tale. He was tried and convicted for his part in the ice company job, but before he left Los Angeles County Jail for San Quentin, he nearly made good on his promise to get even with the man who had dropped a dime on the gang.

The snitch was Roy Melendez. Melendez and Gilkye encountered each other in the County Jail where, according to witnesses, Gilkye “roared like an infuriated animal” when Melendez was placed in lock-up. Gilkye would have murdered Melendez with his bare hands if jail attendants hadn’t intervened.

Melendez may have met a bad end even though Gilkye wasn’t able to lay another finger on him. When Melendez failed to appear in court on a bum check charge an unnamed official opined: “Either Melendez has been killed or they have made it so hot for him he is afraid to show up.” A bench warrant was issued for Melendez, but he was nowhere to be found.

Members of the Sheriff’s Department breathed a sigh of relief. The Burton gang’s brief reign in Los Angeles was over.

* * *

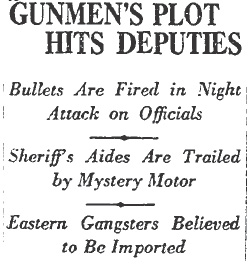

Late in February 1923, two men from Chicago arrived in Los Angeles. The men weren’t tourists, they were on a mission to assassinate the deputies they held responsible for killing Edward Burton and two members of his gang during the shootout at Union Ice Company. The men made inquiries around town in an attempt to learn as much as they could about their targets. While the hitmen were compiling dossiers on their targets, the targets themselves were conducting their business as usual. Deputies William Bright, Spike Modie, Chester Allen and Norris Stensland didn’t know they were being hunted.

At about 1 a.m. on the morning of March 7, 1923, William Bright and Spike Moody left Sheriff’s headquarters. They climbed into Moody’s Stutz and headed up Broadway. They turned west on Temple and continued down the dark, deserted street. After traveling a few blocks they eyeballed a sedan with the side curtains pulled down. They wouldn’t have paid the automobile much attention except that it was trailing them too closely for their comfort. Knowing that they had enemies in the underworld Moody and Bright readied their weapons. As they prepared themselves for a possible gunfight, Moody and Bright watched the sedan suddenly swing off into a side street and disappear.

A few blocks later the mysterious sedan lurched out of a side street onto Temple and passed the Stutz at a high rate of speed. Moody and Bright saw the side curtains part and a shotgun appear. A second shotgun appeared from the tonneau, the rear passenger compartment of the sedan, and both unleashed a volley fire at Modie and Bright. The deputies pulled out their revolvers and returned fire. Bright fired through the windshield of the Stutz. Fortunately for the deputies, the would-be assassins aim went high when their sedan hit a pothole.

Stutz c. 1923

Moody jammed his foot down on the accelerator and gave chase as the sedan drew away. Bright continued to return fire. Bright may have scored a hit. The sedan skidded across the street into a telephone pole. The sedan sagged with one broken wheel. Three men jumped from the car and fled, but not before firing again at the deputies.

Bright and Moody gave chase on foot but the men vanished into the darkness. Returning to the crippled sedan Bright found a hat with a jagged hole through the crown. The wearer had narrowly escaped death. The hat bore the name of a Chicago hatter.

Sheriff’s investigators located the gunmen’s hotel room. They also identified a few of the shooters acquaintances who, under orders from Sheriff Traeger, were kept under surveillance.

Deputies Bright, Moody, Stensland and Allen prepared themselves for the possibility of another attack–but it never came. The Burton gang seems to have departed Los Angeles forever.

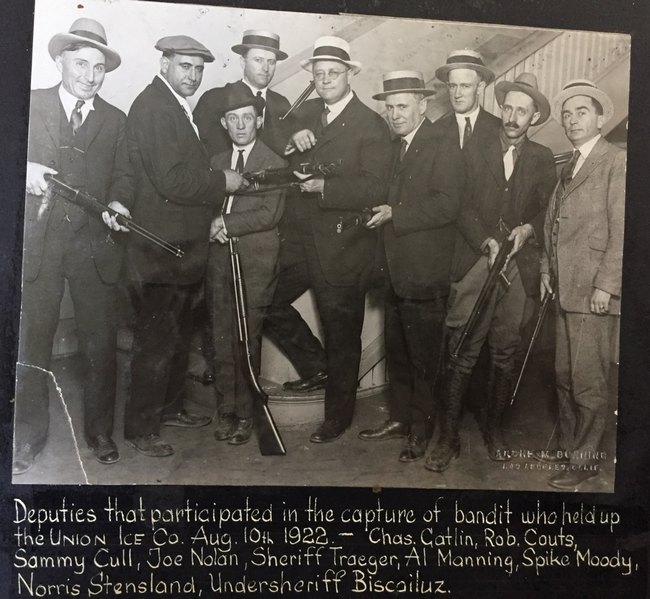

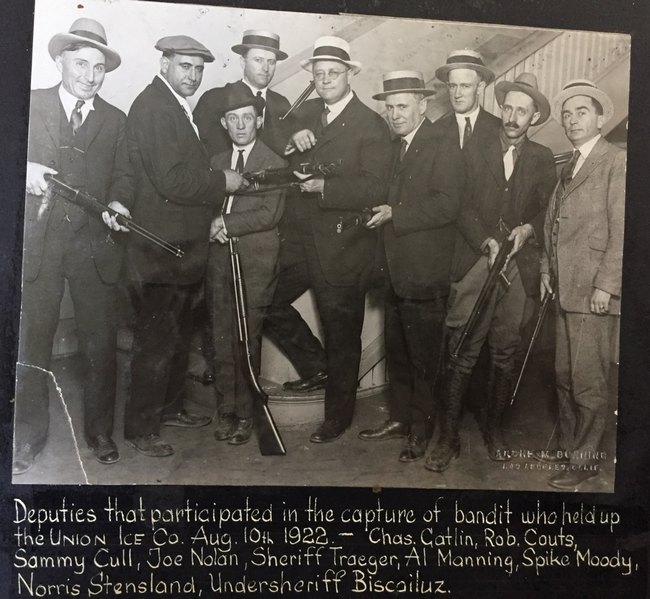

This is such a great photo I decided to post it again!

NOTE: Once again, I am indebted to Mike Fratantoni. His knowledge of L.A.’s law enforcement and criminal history is encyclopedic.

It can be frustrating to pin down accurate spellings of proper names in these historic tales. Often reporters phoned a story into a rewrite person at the newspaper who phonetically spelled a person’s name. Edward Burton was in some reports, Edwin. Another example, Spike Moody’s surname has appeared as Modie. Judging from the above photo it should be the former spelling.

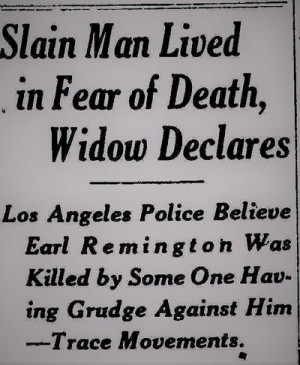

Less than a week into the investigation police discovered that Earle was the victim of extortion — a blackmail scheme run by a man and woman. The woman had allegedly seduced Earle then told him it would cost him big time for her to keep her mouth shut about their affair.

Less than a week into the investigation police discovered that Earle was the victim of extortion — a blackmail scheme run by a man and woman. The woman had allegedly seduced Earle then told him it would cost him big time for her to keep her mouth shut about their affair.

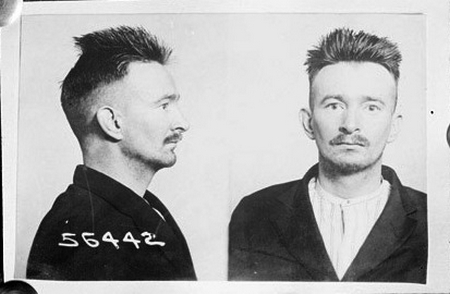

Burton was released on $10,000 [equivalent to $145k in current dollars] bail while Sheriff’s investigators continued to dig into his life and the lives of his companions. No one was surprised to find that Burton was a career criminal with numerous aliases–among them, Charles Mullen. Burton/Mullen fit the description of the man who had shot Motor Officer Bandle; and the car found near the scene of the shooting was registered to Mullen. An unlikely coincidence.

Burton was released on $10,000 [equivalent to $145k in current dollars] bail while Sheriff’s investigators continued to dig into his life and the lives of his companions. No one was surprised to find that Burton was a career criminal with numerous aliases–among them, Charles Mullen. Burton/Mullen fit the description of the man who had shot Motor Officer Bandle; and the car found near the scene of the shooting was registered to Mullen. An unlikely coincidence.