Bernice and Carlyn drove around the city with no destination in mind. Bernice ordered her sister to stop at a drugstore on Sawtelle Blvd. Bernice bought a bottle of veronal cubes and before Carlyn could make a move to stop her, she swallowed all of them. Bernice realized the dose could be fatal, so she started to scream and cry. Carlyn thought fast. She saw a bus stopped at the side of the road, so she pulled over to ask the driver for directions to the nearest hospital. Carlyn and the bus driver drove Bernice to Hollywood Hospital; where she lapsed into a coma. The doctors gave Bernice a fighting chance. Darby fared a little better than his wife. The twenty-five cents’ worth of acid damaged one half of his face, but his doctors felt they could save his eyesight. Sadly, they were mistaken. About three weeks after Bernice’s attack, Darby lost sight in one eye.

While Bernice was in the hospital, and Darby recuperated at home. Detectives tried to piece together the complete story. In particular, the motive for the crime. Carlyn provided a piece of the puzzle. She produced a note, written by Bernice, which blamed Mrs. Day, Sr. for the marital discord between the newlyweds.

“Darby: I’m as sane as can be, but after your mother acted the way she did and would have anything to do with you after I saw you this afternoon, I guess it’s quits. I love you from the bottom of my heart and they say love will go to extremes. We are both in the same fix and you will never find a love as true or pure as mine. Mother-in-laws (sic) should not live with young married people. Love, Bernie,”

Bernice woke up, and since she was unwelcome at the Beverly Hills house, she stayed with her mom and sisters in their apartment at 529 South Manhattan. The police found Bernice and Carlyn there and took them into custody.

Bernice stuck to her ridiculous story, claiming that she doused Darby with acid when the cork flew out of the bottle. Alienists examined her and determined she had the mind of a ten-year-old girl.

Once the jury saw the damage Darby had suffered, they didn’t care if Bernice was a clumsy ten-year-old girl in the body of a 20-year-old woman; they found her guilty. The jury cut Carlyn a break. They found her not guilty of being an accomplice.

Bernice got one to fourteen years in prison.

She could not stay out of trouble. Police rearrested her for speeding while she was out on bond, pending an appeal.

For months Bernice remained a free woman, but California’s high court denied her appeal and by mid-August 1926, the Acid Bride was San Quentin bound.

The press caught up with her as she was about to board the train that would take her to San Quentin. She told them, “I have no bitter feelings against anyone. I have nothing to say about the case, as there has been too much said already.”

Darby Day Jr. and his family returned to Chicago, where he divorced Bernice. Even with the divorce, rumors suggested Darby and Bernice would reconcile on her release from prison. The rumors may not have been as loony as they sounded.

In a move that shocked everyone, Darby made a plea to the Governor of California to set Bernice free. He said, “Bernice has been punished sufficiently for her hasty act, just as I have suffered, but this is the time to forgive, make amends, and then forget. I am not attempting to shield her, nor to belittle the offenses, but I will do what I can to bring about her release.”

The governor was not as forgiving as Darby, and Bernice’s bid to win a pardon failed. The parole board paroled Bernice at the end of 1927, after she had served only fourteen months. Too short a sentence for the agony she caused Darby.

The beautiful young parolee said she wanted to put her time in prison behind her. She summed up her fourteen months in San Quentin for reporters saying, “Association with approximately 100 women, white and black, brown and yellow, some good the others mostly bad, all milling back and forth like animals in damp and stuffy quarters where the air is none too good, daily disputes, wrangles, bickering, real fist fights at times and a good deal of hair pullin’—such a life is enough to take the heart out of anyone, especially when one has not been accustomed to such associations.”

Her snobbery and lack of self-awareness speak volumes about her immaturity and selfishness. Pretty on the outside, ugly on the inside.

Bernice denied the rumors that she and Darby would reconcile. She told reporters, “I’m glad he got a divorce, for I never want to see or hear of him again. As for the public, all I ask is that they let me alone.”

Bernice and her family returned to Chicago. Evidence suggests they all moved to Florida, and Bernice remarried.

In a tragic PostScript to the case, Darby Day Jr. died under anesthesia in a Santa Monica hospital on February 4, 1928.

His death hastened by Bernice’s vicious attack.

Close on the heels of the first man’s visit to Cote’s home another young man, twenty year-old Alfred Dobriener of

Close on the heels of the first man’s visit to Cote’s home another young man, twenty year-old Alfred Dobriener of  Detective Lieutenant S.R. Lopez of the the LAPD said that Pearl had either gone to the end of the bus line and hiked up Franklin to take in the view alone, or she had ridden up in the car with the two men to the top of the hill. By virtue of its seclusion and spectacular views the spot was a local lover’s lane. But why would Pearl have gone there with two men?”

Detective Lieutenant S.R. Lopez of the the LAPD said that Pearl had either gone to the end of the bus line and hiked up Franklin to take in the view alone, or she had ridden up in the car with the two men to the top of the hill. By virtue of its seclusion and spectacular views the spot was a local lover’s lane. But why would Pearl have gone there with two men?”

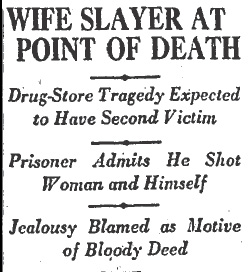

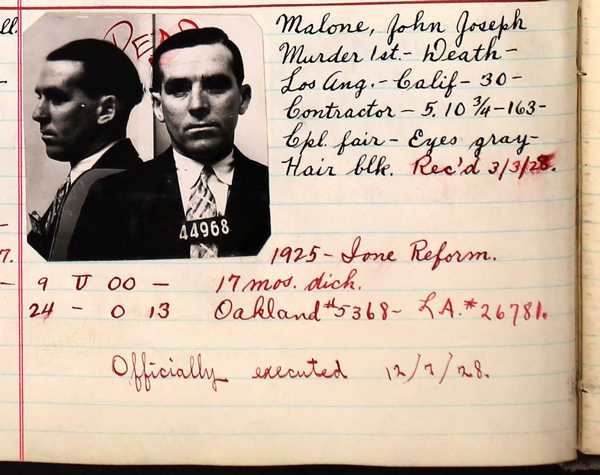

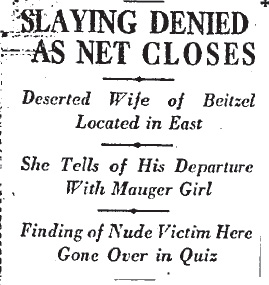

By December 1927 twenty-three-year-old Ruth Malone had been in Los Angeles for about 4 months. She’d fled Aberdeen, Washington to escape her husband John, a jealous and violent drunk. She used her mother’s address at 244 North Belmont Avenue, but lived with a girl friend in an apartment at 9th and Flower. She kept the address of the apartment a secret just in case John tried to find her. She worked half a mile from the apartment at a drug store on East Twelfth between Santee Street and Maple Avenue. Ruth had spent the last few months seriously contemplating divorce but she wasn’t in any hurry to confront John.

By December 1927 twenty-three-year-old Ruth Malone had been in Los Angeles for about 4 months. She’d fled Aberdeen, Washington to escape her husband John, a jealous and violent drunk. She used her mother’s address at 244 North Belmont Avenue, but lived with a girl friend in an apartment at 9th and Flower. She kept the address of the apartment a secret just in case John tried to find her. She worked half a mile from the apartment at a drug store on East Twelfth between Santee Street and Maple Avenue. Ruth had spent the last few months seriously contemplating divorce but she wasn’t in any hurry to confront John.

Investigators learned that John was 29-years-old and that he had an arrest record. He’d been busted in Oakland on October 10, 1917 on a burglary charge and later in San Francisco for violation of the State Poison Act (a drug charge). John had been in Los Angeles for a few weeks. He was staying at a hotel just a few blocks away from Ruth’s workplace.

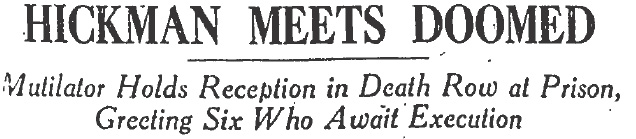

Investigators learned that John was 29-years-old and that he had an arrest record. He’d been busted in Oakland on October 10, 1917 on a burglary charge and later in San Francisco for violation of the State Poison Act (a drug charge). John had been in Los Angeles for a few weeks. He was staying at a hotel just a few blocks away from Ruth’s workplace. On March 20, 1928 John and several other death row inmates welcomed a newcomer to their ranks, William Edward Hickman. Hickman, who had given himself the nickname “The Fox” had been sentenced to death for the brutal mutilation murder of 12-year-old Marion Parker, a crime he had committed only ten days after John had killed Ruth. The two dead men walking had met in the Los Angeles County Jail while each was awaiting trial. John cornered Hickman on one occasion and blamed him for inciting the public to a renewed interest in capital punishment–resulting in his own date with the hangman.

On March 20, 1928 John and several other death row inmates welcomed a newcomer to their ranks, William Edward Hickman. Hickman, who had given himself the nickname “The Fox” had been sentenced to death for the brutal mutilation murder of 12-year-old Marion Parker, a crime he had committed only ten days after John had killed Ruth. The two dead men walking had met in the Los Angeles County Jail while each was awaiting trial. John cornered Hickman on one occasion and blamed him for inciting the public to a renewed interest in capital punishment–resulting in his own date with the hangman. John’s sentence was automatically appealed but the State Supreme Court upheld the death penalty. Judge Fricke re-sentenced John to hang. Unless something changed he would meet his end on December 7, exactly one year to the day since Ruth’s murder. John had evidently changed his mind about dying since his suicide attempt because he was part of a Thanksgiving escape plot that failed. To prevent him from any further attempts to tunnel out of San Quentin he was moved to the death cell.

John’s sentence was automatically appealed but the State Supreme Court upheld the death penalty. Judge Fricke re-sentenced John to hang. Unless something changed he would meet his end on December 7, exactly one year to the day since Ruth’s murder. John had evidently changed his mind about dying since his suicide attempt because he was part of a Thanksgiving escape plot that failed. To prevent him from any further attempts to tunnel out of San Quentin he was moved to the death cell.

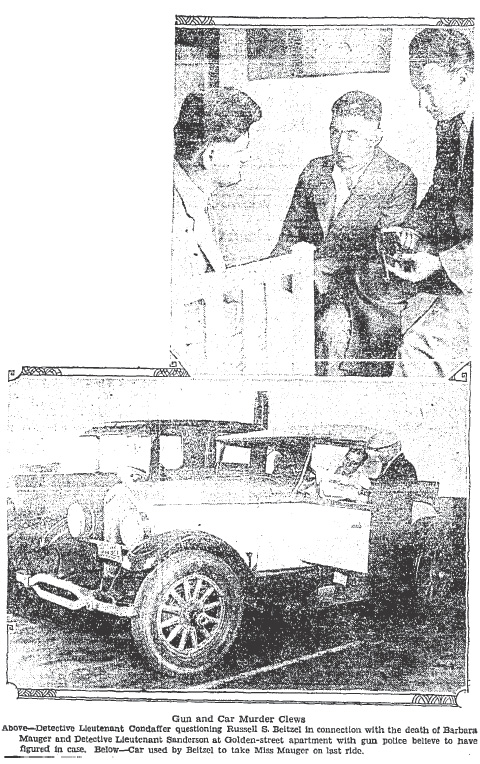

![Convicted murderer, Russell Beitzel getting a shave in prison as other inmates look on, Los Angeles, Calif., 1928. [Photo courtesy of UCLA Digital Collection]](https://derangedlacrimes.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/03/beitzel-shaved_ucla.jpg)