By mid-May 1928, Christine Collins had been going through the motions of living for weeks as she waited for word of her missing son Walter. Her job as a telephone operator kept her busy during the day, but at night all she could do was lie in bed and stare at the ceiling.

If Christine read the newspapers she may have seen a story about two boys who had gone missing from Pomona. The boys, Nelson and Lewis Winslow, had vanished after attending a meeting of the Pomona Model Yacht Club.

Nelson was described as: 10 years of age, light hair, blue eyes, 4 feet in height, dressed in a blue shirt and knickers. Lewis was described as: 12 years of age, 4 feet 3 inches in height, light hair, blue eyes, dressed in a regulation Boy Scout uniform — it was also noted that Lewis had a nervous temperament.

According to their family the boys had not been in any trouble and there was no reason for them to have run away from home.

Nelson and Lewis had been gone for a couple of weeks before the Winslows finally received a note from them written on a flyleaf torn from a book issued by the Pomona Public Library. The note said that they’d left Pomona and were off to Mexico to find gold. Pomona cops sent telegrams to border authorities asking them to detain the boys if they were found attempting to cross into Mexico.

There were no sightings of Nelson and Lewis at the border, and no further clues to their whereabouts surfaced. Mr. and Mrs. Winslow found themselves consigned to the same purgatory inhabited by Christine Collins. They were all fearful of hope and ashamed of doubt, and each dawn brought renewed heartache.

There were no sightings of Nelson and Lewis at the border, and no further clues to their whereabouts surfaced. Mr. and Mrs. Winslow found themselves consigned to the same purgatory inhabited by Christine Collins. They were all fearful of hope and ashamed of doubt, and each dawn brought renewed heartache.

Because the Winslow home was thirty miles east of the Collins’ Lincoln Heights bungalow, cops didn’t make a connection between Walter and the Winslow boys. The authorities also had no reason to connect the disappearances to the discovery of the headless body of a Latino boy found on a roadside in La Puente.

The seemingly unrelated cases would come together in a perfect storm of horror in September 1928. It began when a young Canadian woman, Jessie Clark, decided to check up on her younger brother, 15 year old Sanford. She’d been worried about Sanford ever since he’d left with their uncle, Gordon Stewart Northcott, two years earlier. Jessie was concerned enough about her brother’s welfare to travel to Northcott’s ranch in Wineville, California to see for herself exactly what was going on.

Jessie spent a short time at the Wineville ranch, but it was long enough for her to confirm that her uncle was terrorizing and abusing Sanford — and it was just enough time for her uncle to assault her too. When she returned to Canada she told her mother, Winnefred, all about her terrifying visit to Wineville. Her mother immediately dropped a dime on Gordon to U.S. authorities.

Northcott saw agents driving up the road to his ranch, so he told Sanford to stall them or he would shoot him. Sanford had had two years of reasons to believe that his uncle was capable of murder, so he did as he was told.

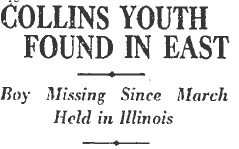

Gordon and his mother, Sarah Louise, fled to Canada, but were quickly busted in British Columbia. While extradition of the two fugitives was being sought, Sanford Clark was relcounting a tale of sexual depravity and unimaginable brutality to the police. It was Clark’s statement that would connect his uncle to Walter Collins, and then to the Winslow boys, and finally to the unidentified headless boy who had been found in La Puente. Clark was also able to lead detectives to physical evidence of the sadistic slayings.

Among the evidence found at the farm was an aviation magazine, the paper from which matched that upon which a note from the Winslow boys had been written. Sanford led police to grave sites on the farm in the hunt for human remains. The graves had been disturbed, and they had likely been emptied by Gordon and his mother Sarah and the contents burned in the desert sometime during the month of August.

The extradition of the fugitive mother and son was successful, and in December the pair arrived in Los Angeles to stand trial.

On December 3rd, Gordon Stewart Northcott confessed to the slayings of Nelson and Lewis Winslow and the headless Mexican boy. Sarah Louise Northcott confessed to the murder of Walter Collins.

NEXT TIME: A fool for a client, a city changes it name, and the Wineville Chicken Coop murder case ends.

![Lewis and Nelson Winslow [Photo courtesy of LAPL]](https://derangedlacrimes.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/winslows00027495.jpg)

![Northcott's murder farm. [Photo courtesy of LAPL]](https://derangedlacrimes.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/murder-farm_00027479.jpg)

![Walter Collins [Photo courtesy LAPL]](https://derangedlacrimes.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/walter-collins00027493.jpg)

![The boy who would be Walter -- Arthur Hutchins, Jr. [Photo courtesy LAPL]](https://derangedlacrimes.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/hutchins00027498-182x300.jpg)

![Billy Fields was an alias used by Arthur Hutchins, Jr. [Photo courtesy LAPL]](https://derangedlacrimes.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/billy00027483.jpg)