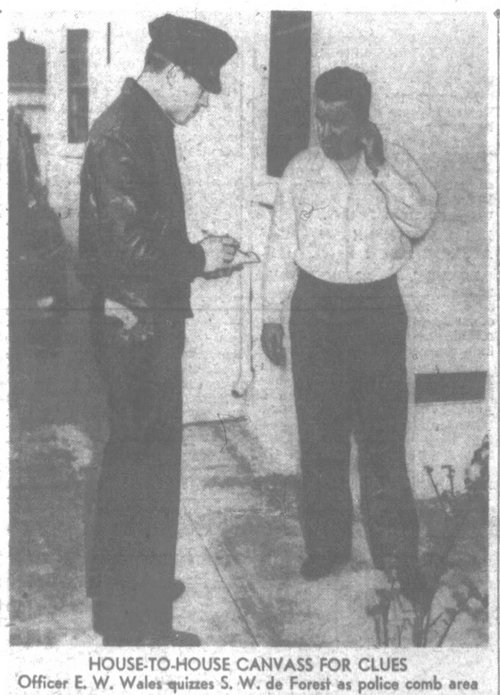

Forty uniformed police officers began a house-to-house search around Norton Avenue, Coliseum Drive and 39th Street, where Elizabeth Short’s body was found. The killer left no evidence at the body dump site, so the police wanted to find the “torture chamber” where Beth was murdered and cut in half.

Detective Lieutenant P. P. Freestone said, “We hope to find someone who saw her during the blank period preceding her death, or who might have heard screams when she was being tortured. The police are in uniform so that housewives won’t refuse to answer their rings.”

The officers found many people willing to talk.

Paul Simone, a painting contractor, told officers he overheard a bitter quarrel between someone he thought was Beth and another woman. The women argued in apartment 501 at 1842 N. Cherokee Avenue in Hollywood, where Beth had lived with several roommates.

Simone said, “It was pretty hard language.” He said the last thing he heard was “Oh, nuts to you,” from the other woman. “Nuts to you” must have been harsh language for women in 1947.

The problem with Simone’s story is he claimed to have heard the altercation on January 11th. Later, they proved there were no credible sightings of Beth from January 9th until the 15th, when Betty Bersinger found her body.

In desperation, police rousted anyone who looked suspicious to them. They arrested one man, only to find out he was distraught because his dog was sick.

Police sought women, too. They launched a “woman hunt” for a pair of brunettes seen with Beth in Hollywood. Newspapers hinted the two women might be lesbians. They described the places the women visited as “Hollywood women’s hangouts.” Nothing came of the brunettes.

Walter A. Johnson, of 3815 Welland Steen, told officers on Tuesday, January 14, he was burning trash across the street from the vacant lot where they found Beth’s body the next morning. He noticed a light tan or cream four-door sedan, possibly a 1935, and a man standing near it. The man’s behavior piqued Johnson’s curiosity. “He walked a little way up the street, then came back, crossed over and looked into my car, and finally got into his own and drove off.”

Johnson got in his car and followed the mystery man, but lost him.

Police asked why he had not come forward earlier. Johnson said he reported the incident, “but nothing came of it.”

Another witness surfaced. A cab driver, I. A. Jorgenson, told detectives he believed he picked Beth and a man friend at Sixth and Main Street on the night of January 11. He said he was “almost positive” the woman was Beth. Jorgenson said the couple hailed his cab, and they instructed him to take them to a Hollywood motel. The police withheld the motel’s name but told reporters they would question the employees.

None of the tips gleaned from the neighborhood sweep resulted in a solid lead. The police questioned hundreds of people, asking questions like the following:

“Do you know anybody in the neighborhood who is mentally unbalanced?”

“Anybody of whom you were suspicious after reading about the Elizabeth Short murder?”

“Do you know of any medical students?”

“Did you find any strange items in your yard or incinerator?”

Police chemist Ray Pinker worked long hours to bring a solution to the murder. He sought to establish Beth’s blood type after a gray, bloodstained blanket turned up late on January 22.

A bloodstained tarp, 3 by 6 feet, found near Indio, was also being examined in the lab.

Desperate to solve the case, the Los Angeles City Council offered a $10,000 (equivalent to $141,368.00 in current USD) reward; but the city attorney felt it to be inappropriate. City council member Ed Davenport, perhaps naively, said an informer “should be prepared to talk without being paid by the city. Maybe now he will come forward without waiting for any reward to be offered.”

If such an informer existed, he or she has never come forward.