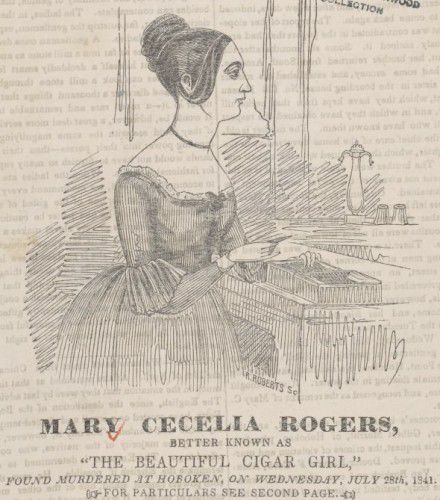

MARY CECILIA ROGERS

Edgar Allan Poe’s The Mystery of Marie Roget, is cited as the first murder mystery based on details of an actual crime. I am skeptical of firsts, but if Poe’s story is not the first, it is an early entry. It appeared in Snowden’s Ladies’ Companion in three installments, November and December 1842 and February 1843.

Behind Poe’s tale of Marie Roget is the murder of Mary Cecilia Rogers.

Rogers, a tobacco shop employee, became known as the Beautiful Cigar Girl. She disappears on October 4, 1848, and local papers report her elopement with a naval officer. She returns later, sans husband.

She disappears again on July 25, 1841. Friends see her at the corner of Theatre Alley, where she meets a man. They walk off together toward Barclay Street, ostensibly for an excursion to Hoboken.

Three days later, H.G. Luther and two other men in a sailboat pass by Sybil’s Cave near Castle Point, Hoboken. Floating in the water they see the body of a young woman. They drag it to shore and contact police.

According to the New York Tribune, Rogers is “horribly outraged and murdered”. Questions regarding Rogers’ death remain. It is alleged she ended up in the river following a failed abortion. The scenario is credible, in part, because her boyfriend committed suicide and left a note suggesting his involvement in her death.

GRACE BROWN

I love it when a novel is based on a true crime. One of my favorites is An American Tragedy by Theodore Dreiser. Dreiser draws inspiration from a murder in the Adirondacks.

In 1905, Chester Gillette takes a job as a manager in an uncle’s skirt factory in Cortland, New York. It is there he meets factory worker, Grace Brown. They begin an affair and she becomes pregnant.

Chester is neither interested in being a husband, nor in being a father. He takes Grace on a trip to the Adirondack Mountains in upstate New York. Using the alias, Carl Graham, Chester rents a hotel room, and a rowboat.

Grace believes the hotel is where they will spend their honeymoon following a visit to the local justice of the peace. In anticipation of her new life with Chester, Grace packs all of her belongings in a single suitcase.

Chester’s suitcase is small. He is not beginning a life with Grace.

On July 11, the couple takes a rowboat out into the middle of Big Moose Lake. There is no marriage proposal. No wedding ring. He beats her over the head with his tennis racquet and pushes her overboard to drown.

On July 13, 1906, The Sun reports the tragic drowning of a couple in Big Moose Lake. Grace’s body floats to the surface the next day. The body of her companion, Carl Graham, is missing.

Fearing he is dead, police search for Carl. They soon learn the true identity of Grace’s companion. He is alive, well, and his name is not Carl. Police arrest Chester. He denies responsibility for Grace’s death. He insists she committed suicide. The bad news for Chester is none of the physical evidence supports his version of events.

The jury shows no mercy—they find him guilty and sentence him to death.

On March 30, 1908, they execute Chester in the electric chair at Auburn Prison in Auburn, New York.

LOIS WADE

March 4, 1932.

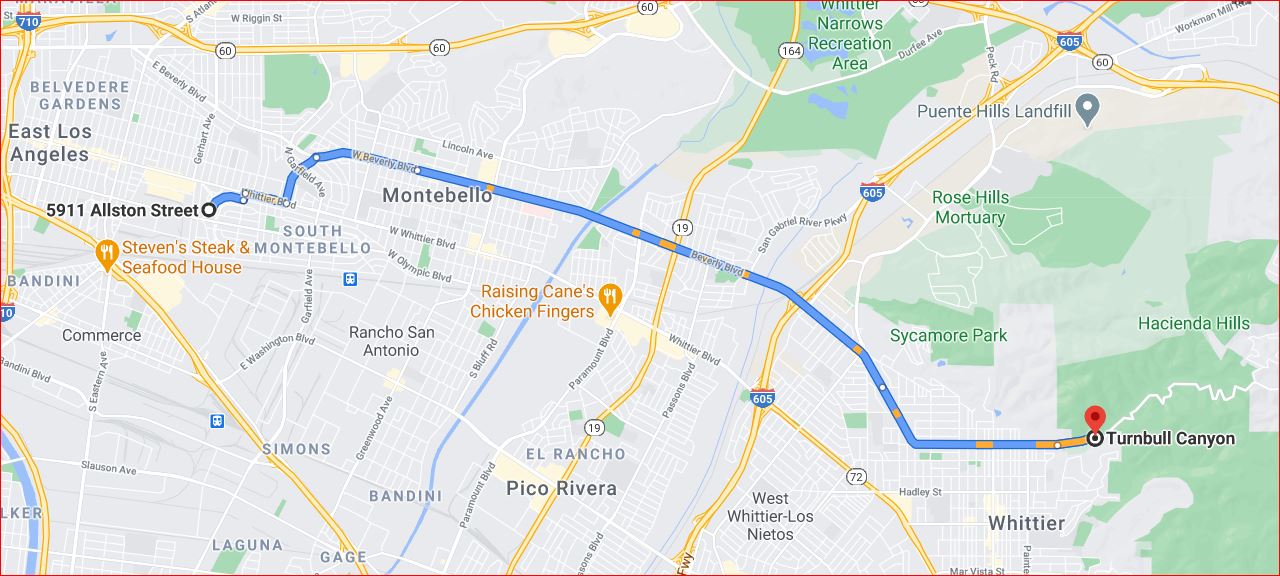

Soaked to the skin, bleeding from the head, and covered in bruises, seventeen-year-old Lois Wade stumbles into the road near Mountain Meadows Country Club in Pomona. A Good Samaritan takes her to Pomona Valley Hospital.

The hospital calls the Sheriff’s department, and deputies arrive to take Lois’ statement. She tells them a terrifying story.

She is is walking from downtown Pomona to her parent’s home at 349 East Pasadena Avenue, when a stranger pulls up alongside her and offers her a ride. She accepts, but rather than taking her home, the man stops his car on Walnut Avenue near an abandoned well and beats her.

Lois’ attacker forces her into the well and shoves her down witht a pole when she attempts to climb out. When Lois vanishes from his view, the man gets in his car and drives away.

The motiveless attack makes little sense, and deputies question Lois’ account. The next day, she revises her story.

Her attacker is not a stranger as she originally claims; he is her nineteen-year-old married lover, Frank Newland.

Deputies Killion and Lynch arrest Frank at his home at 918 South San Antonio Street, Pomona. They book him on a charge of assault with intent to commit murder. Frank denies the attack.

As Lois lay in serious condition in the hospital, the D.A. revises charges against him to include statutory rape. Because of the severity of Lois’ wounds and her inability to appear in court, Judge White resumes Frank’s hearing at Lois’ hospital bedside.

Within a month of the attempt on Lois’ life, Frank goes to trial. Local newspapers pick up on the similarities between Frank and Lois and the characters in Theodore Dreiser’s An American Tragedy.

Future Los Angeles mayor, Fletcher Bowron, sits on the bench. Public interest in the trial is high and draws an enormous crowd—the largest since the 1929 rape trial of theater mogul Alexander Pantages.

The trial begins on April 28; Lois takes the stand, and the courtroom hangs on her every word.

Lois is low-key and demure as she testifies to her ordeal.

“By prearrangement we met on a corner in Pomona. We went in his roadster to the Mountain Meadows Country Club, where he drove off the road and stopped the car. We sat in the car for a half-hour; yes, we kissed and loved. He then suggested that we walk over to an old windmill and abandoned well nearby.”

“We looked in the well and then suddenly he turned around and struck me over the head with a club. I fell to the ground. He struck me eight or ten times more and kicked me several times.”

Frank grabs Lois by the feet and drags her, struggling and screaming ten feet to the well. No match for Frank, he overpowers her and throws her in the well.

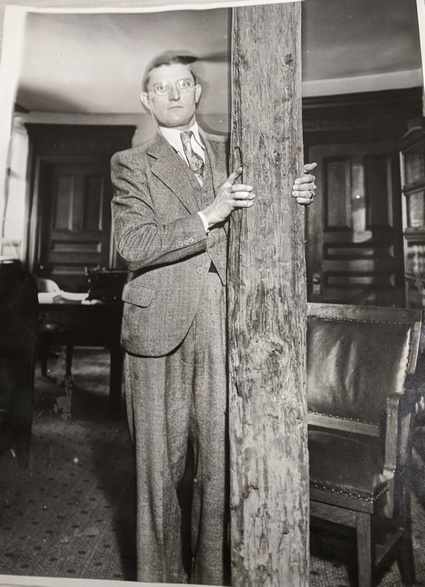

Lois lands in twenty-five-feet of water. She bobs to the top, and fights for her life. Frank uses a railroad tie to shove Lois under water. A photo of Deputy W.L. Killon, puts the size of the weapon into perspective.

LOIS WADE

Convinced Lois is dead, Frank gets into his car and drives away.

Lois claws herself up the wall of the well. She crawls over the edge, tumbles onto the ground, then rises and lurches into the street to summon help. A man stops his car to render aid. Amazingly, Lois’ Good Samaritan is a doctor.

Dr. Roy E. St. Clair testifies to finding Lois in the road.

“I was driving to Pomona on the Mountain Meadows Road about 8:30 p.m. last March 4 when I heard a cry and the lights on my car picked up the figure of Miss Wade standing with her right arm out-stretched. I backed up my machine, and she came to the door and said ‘Take me to a doctor.’”

NEXT TIME: A strange ending.