On October 29, 1941, a story appeared in the L.A. Times about a man, Monty J. llingworth, who had been arrested for the 1937 murder of his wife, Hallie, in Clallam County, Washington.

On October 29, 1941, a story appeared in the L.A. Times about a man, Monty J. llingworth, who had been arrested for the 1937 murder of his wife, Hallie, in Clallam County, Washington.

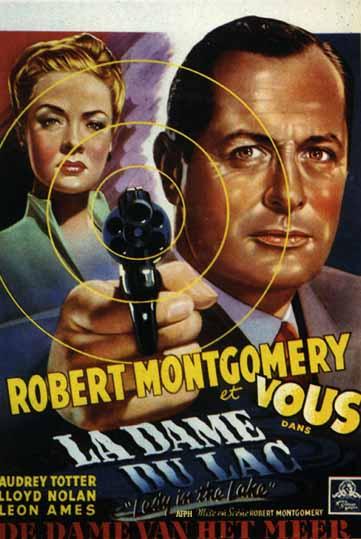

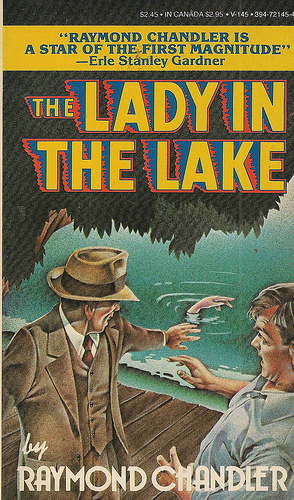

Because Illingworth had committed the crime in Washington it wasn’t covered extensively here, but I have to wonder if Raymond Chandler saw the piece in the newspaper and was inspired to write THE LADY IN THE LAKE (published in 1943).

The true story of the Lady began on July 6, 1940 when two fishermen found the well preserved body of a woman floating in the waters of Lake Crescent, near Port Angeles, Washington. The corpse had been wrapped in blankets and tied with heavy rope.

The body was not decomposed as one might have expected, nor was it bloated as “floaters” generally are. Dr. Kaveney, who examined the body, said:

The body was not decomposed as one might have expected, nor was it bloated as “floaters” generally are. Dr. Kaveney, who examined the body, said:

“I never saw a corpse just like this one before. The flesh is hard, almost waxy. She must be nearly as large as when she went into the water. I’d say she is about 5 feet 6 inches in height and that she weighed about 140 pounds when alive.”

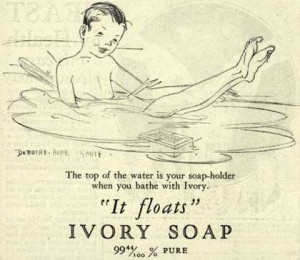

There was a chemical reason for the relatively good condition of the woman’s body, she had saponified, she had literally turned into soap! In fact, she had become very much like Ivory soap, the “soap that floats”.

Even though they were unable to I.D. the woman her cause of death was certain, she had been strangled.

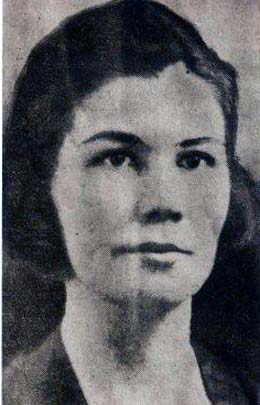

The press dubbed the unknown woman The Lady of the Lake. She was buried as a Jane Doe in a pauper’s grave. She was exhumed a couple of times in an attempt to give her a name, but it wasn’t until criminologist Hollis B. Fultz began to look at missing persons reports from the area that the case came together.

Hollis focused his attention on a missing waitress, Hallie Illingworth. Hallie had been an attractive woman with auburn hair — the corpse also had auburn hair.

Hallie was married to a beer truck driver, Monty Illingworth, at the time of her disappearance. Monty told people that Hallie had run off with a Navy lieutenant commander.

Further investigation revealed that Hallie had never contacted any of her family, which the cops found suspicious. Also suspicious was the fact that Monty had filed for a divorce five months after she’d vanished on the grounds of incompatibility, not desertion.

A chart was made of the dead woman’s unique upper dental plate and advertised in professional journals. Finally a dentist from South Dakota came forward to positively identify The Lady of the Lake as Hallie Illingworth.

Monty had moved to Long Beach, California shortly after Hallie allegedly ran off with a Navy man. Monty wasn’t alone, accompanying him was Elinore Pearson the daughter of a wealthy timber magnate.

Illingworth was arrested at 1351 St. Louis Street, Long Beach. His mother and Elinor Pearson visited him while he was waiting to find out if he’d be extradited to Washington. In his jail cell, Monty turned to face his mother and said: “Mother, you know I didn’t do it; I didn’t.” To which his mother replied: “Yes, I know you didn’t, son.”

The couple had been living as husband and wife yet Elinor was coy when asked if she was married to Monty, she would neither confirm nor deny it.

The truck driver was extradited to Washington where he was tried for Hallie’s murder.

On March 5, 1942 a Washington jury found Monty Illingworth guilty of second degree murder. They’d agreed on the lesser charge because they felt the crime had been one of passion and not premeditation.

Monty was sentenced to life in Walla Walla Prison, but was paroled after only nine years. He returned to California where he lived until his death in the early 1960s.

A writer of Chandler’s caliber wouldn’t have needed anything more than a small newspaper piece to become inspired. Of course I don’t know if Raymond Chandler actually saw the story about the Lady of the Lake, but I like to think so.