Being a researcher is like being an explorer without a map. I set sail and go where the tides take me. It is one reason I love what I do.

On Thursday, I was at the Hall of Justice where I volunteer for the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department Museum. My current project is transcribing a 1895-1896 L.A. County Jail Register and entering the information into a searchable file. The register is a fascinating glimpse into the city and some of its more colorful, and criminal, inhabitants.

Besides entering the details of an arrest: date, suspect name, police officer’s name, type of crime, etc., I document cases when I can find information. There weren’t many murders, but there were plenty of other crimes which merited column space in the local newspapers.

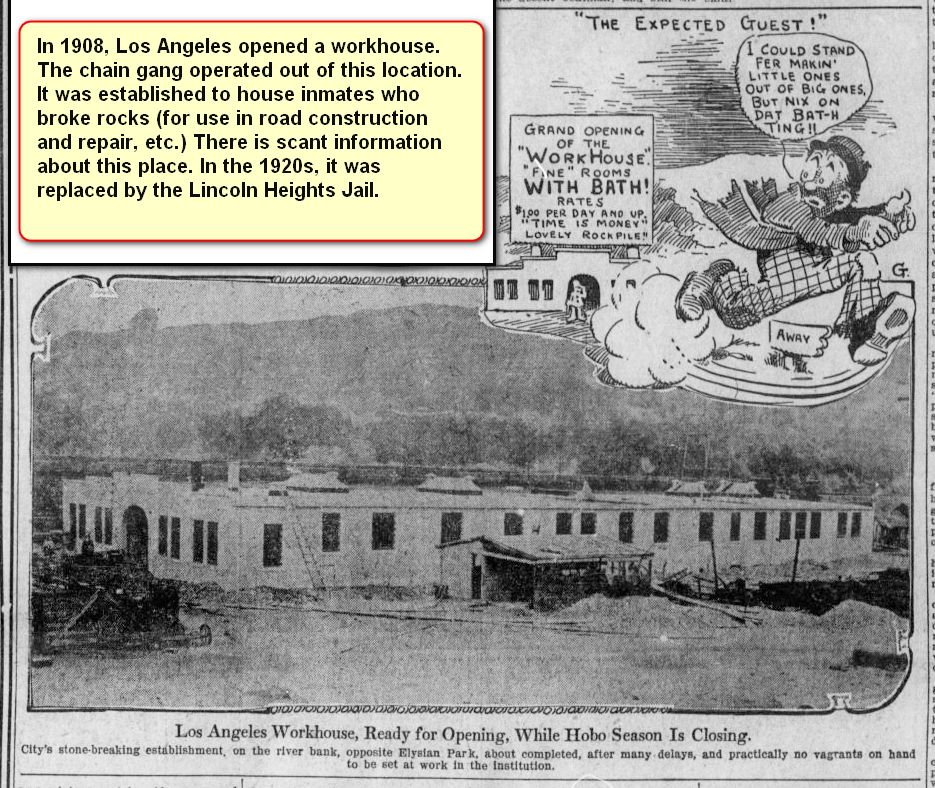

I followed one miscreant right to the door of the Los Angeles County Workhouse about which, I confess, I knew nothing. I dug deeper and found photos of the interior and exterior of the building. Also, a photo and the name of the man in charge, Lt. Charles Dixon.

They officially designated the facility LAPD substation No. 2. Its territory comprised all of Boyle Heights and the entire northern district of the city.

Rumor had it that Lt. Dixon’s assignment was politically motivated. It was, some said, an exile not an opportunity. If Dixon played politics and lost, whose toes did he step on? Chief of Police Edward Kern assigned Dixon to the workhouse; so maybe Dixon crossed Kern and paid for it with a post in the boondocks.

I will dig further into the politics of the era but, meanwhile, I found Chief Kern to be an interesting character in his own right.

Kern’s background was as a teamster and as the chief of supplies for the U.S. Army’s campaign against Geronimo. Like many other former soldiers, Kern landed in Los Angeles.

In 1902, constituents elected him to represent the 7th district on the City Council. Reelected in 1904, he resigned after being appointed police chief–even though it appears he had no law enforcement experience.

In January 1909, Kern continued his public service as an appointee to the Board of Public Works. He lasted two months. Complaints that he was unqualified dogged him, and rather than be removed he quit in March of that year.

Kern battled personal demons and “was given to periodical drunken sprees.” In 1911, he admitted himself to the State Hospital for Inebriates in Patton, California on the advice of his physician, Dr. Sumner J. Quint. Quint became Kern’s legal guardian.

He was unwell when discharged from the hospital. The Los Angeles Times described him as “pitiful” and said “His face was unshaven, haggard and drawn.”

In 1912, Kern went to El Paso, Texas, ostensibly on business. On April 20th, a chambermaid found his body in the bathtub of the hotel where he was staying. He died of a self-inflicted gunshot wound to the head. He left no note, but his revolver, a gift from friends in Los Angeles, lay beside his body.

NOTE: Writing this post, I am reminded of an early TV show, THE NAKED CITY, a police procedural set in New York. It always ended with the narrator saying, “”There are eight million stories in the naked city. This has been one of them.”

The population of Los Angeles in 1895 was approximately 75,000. The above story has been one of them.