Russell Thompson refused to believe that his daughter, 7-year-old Alsa, had poisoned anyone. Dr. Edwin Huntington Williams, a psychiatrist, was inclined to agree with him. The doctor examined Alsa and pronounced her abnormal but “…not exactly insane.” He said: “It might be that in periods of epilepsy she has done strange things but it will take much careful observation to determine what is wrong with her. I have made only a casual examination but will make a more detailed one with Dr. Martin G. Carter, superintendent of the Psychopathic Hospital, and Dr. G.H. Steele, assistant superintendent.”

Russell Thompson refused to believe that his daughter, 7-year-old Alsa, had poisoned anyone. Dr. Edwin Huntington Williams, a psychiatrist, was inclined to agree with him. The doctor examined Alsa and pronounced her abnormal but “…not exactly insane.” He said: “It might be that in periods of epilepsy she has done strange things but it will take much careful observation to determine what is wrong with her. I have made only a casual examination but will make a more detailed one with Dr. Martin G. Carter, superintendent of the Psychopathic Hospital, and Dr. G.H. Steele, assistant superintendent.”

Dr. Williams wasn’t alone in believing that epilepsy was an inherited mental defect that could result in criminal behavior. It was one of the conditions which some members of the medical community hoped to eradicate through involuntary sterilization and selective breeding. The social movement that endorsed such repugnant beliefs was known as Eugenics and was practiced in the United States for years before it became part of the Nazis plan to breed a race of Aryan Ubermensch (supermen).

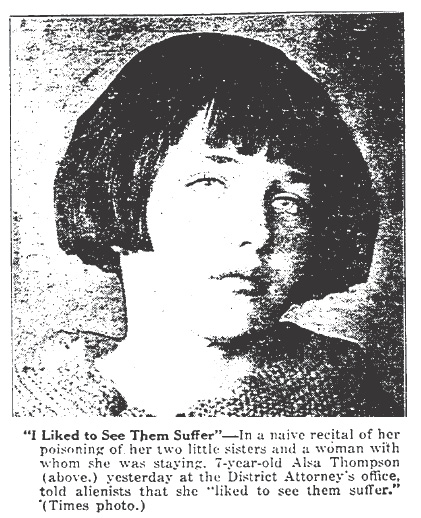

Alsa was calm when she told Dr. Williams about the poisonings. She claimed that when she was a 4-year-old she had killed her twin siblings, and she had confessed to poisoning the food of the Platts family who had taken her and her younger sister in during their parents’ separation and divorce. She also confessed to killing Nettie Steele who had been her caretaker the previous year. Dr. Williams wasn’t convinced that Alsa was guilty of anything but an overactive imagination. About her stories he said: “There is no doubt that she believes them. Until we have checked up on heredity and the child’s history we will be unable to understand just what the trouble is.”

Psychiatrists declared that Alsa was sane. Buron Fitts, the Chief Deputy District Attorney, didn’t seem to know what make of the girl. He said: “Frankly, I don’t know what to think. It’s the most extraordinary case I ever heard of. I don’t know whether to believe the child or not. Her stories sound improbable, but then there is the way she tells them. I just don’t what to think about it yet.”

Psychiatrists declared that Alsa was sane. Buron Fitts, the Chief Deputy District Attorney, didn’t seem to know what make of the girl. He said: “Frankly, I don’t know what to think. It’s the most extraordinary case I ever heard of. I don’t know whether to believe the child or not. Her stories sound improbable, but then there is the way she tells them. I just don’t what to think about it yet.”

Fitts wasn’t the only one confounded by Alsa’s confessions. The Lunacy Commission (no, I didn’t make that up), ruled that the child was mentally sick and bordering on insanity, but that she was not dangerously insane.

Claire finally spoke on her daughter’s behalf: “I do not believe Alsa’s story now. I suppose I have been impressionable, but Mrs. Platts was telling me these things all along and I usually believe the things people tell me.”

Dr. Paul Powers, an associate of members of the Lunacy Commission, spoke to reporters following the hearing. He said: “I think that half what the girl says is true and half false, but that her environment surely has not been the best.”

It was about time that the authorities looked into Alsa’s caretakers. It was Inez Platts who had charged Alsa with attempting to poison her family and no one seemed to have done anything other than take her word for it. During an interrogation Inez admitted that there was at least one night when Alsa was bound hand and foot.

The consensus was that both Alsa and Maxine would be better off away from the Platts’ home. Russell again expressed his belief in Alsa’s innocence: “My child will now be allowed to get the proper care and I am sure it is the best thing in the world for her. I think she is better away from the influences to which she has been subject, including her mother. I have nothing further to say. I will not capitalize in any way on my child.” Russell further denied earlier reports that he and Claire might reconcile. In fact he filed a petition in Juvenile Court asking that his youngest daughter, Maxine, be made a ward of the court until he could be granted full custody.

It was interesting that Russell included Claire as a negative influence in his daughters’ lives. The courts must have agreed with him because he was awarded custody of both Maxine and Alsa. In retrospect it seems obvious that Alsa’s unsettling confessions had been false—the product of twisted suggestions by an adult—but whether it was Claire or Inez it’s impossible to say.

Just because Alsa wasn’t really a Baby Borgia, doesn’t mean that there is no such thing as a killer kid. In May 1929, four years after Alsa made headlines in L.A., six-year-old Carl Newton Mahan was tried in eastern Kentucky for the murder of his friend, 8-year-old Cecil Van Hoose. The two had been out looking for scrap metal to sell. They fought over a piece of scrap and Cecil smacked Carl in the face with it. Carl shot Cecil to death with his father’s shotgun. He was sentenced to 15 years in reform school, but a judge issued a “writ of prohibition” which allowed him to remain free. There are other cases of kids who kill, but Alsa wasn’t one of them.

Alsa and Maxine must have been relieved when they moved to Orange County to live with Russell. As far as I can determine from census and other records once Alsa was away from the Platts’ and the influence of her mother she lived a normal life. She passed away in April 1994 at age 77.