him in all sorts of schemes, most of which smacked of extortion. The cops thought that the scams were primarily small ones, until they uncovered evidence that John was attempting to merge several cults into a “spiritualist trust”. Among the plans he had for the trust were: Mexican distilleries, deals in bat guano, and investments in copper mines and oil stocks. He planned to operate the trust out of a home offered for sale by Mrs. Dorothy Parry. John represented himself to Dorothy as the agent for a purchaser who could afford the asking price of $70,000 (equivalent to nearly $10M in 2016 dollars). But rather than putting Dorothy together with a buyer, John bombarded her with letters and poems. Dorothy told investigators: “The man’s persistence was so annoying that I had to move and asked my hotel not to give my forwarding address. But somehow Clarke managed to obtain it and followed me to this address. As the result of his visits I have been afraid to answer the door bell or go to the telephone.”

him in all sorts of schemes, most of which smacked of extortion. The cops thought that the scams were primarily small ones, until they uncovered evidence that John was attempting to merge several cults into a “spiritualist trust”. Among the plans he had for the trust were: Mexican distilleries, deals in bat guano, and investments in copper mines and oil stocks. He planned to operate the trust out of a home offered for sale by Mrs. Dorothy Parry. John represented himself to Dorothy as the agent for a purchaser who could afford the asking price of $70,000 (equivalent to nearly $10M in 2016 dollars). But rather than putting Dorothy together with a buyer, John bombarded her with letters and poems. Dorothy told investigators: “The man’s persistence was so annoying that I had to move and asked my hotel not to give my forwarding address. But somehow Clarke managed to obtain it and followed me to this address. As the result of his visits I have been afraid to answer the door bell or go to the telephone.”

While continuing to pursue Dorothy, John was able to convince several more women to sign “soul contracts.” Helen Isabelle McGee’s contract read in part: “I agree with John Bertrum Clarke to enter with him into a higher spiritual development for at least two years. I will do everything possible to permit him to restore my full youth…and will be guided by him in both objective and subjective…”

Soul contracts and shady real estate deals were bad enough, but what about the possibility that John had been involved in the suspicious deaths of two women with whom he had been involved?

Soul contracts and shady real estate deals were bad enough, but what about the possibility that John had been involved in the suspicious deaths of two women with whom he had been involved?

The first death was that of John’s former housekeeper. Her body was found in the lake at Westlake Park across the street from the apartment John occupied at the time. Shortly before her death the unnamed woman had deeded a piece of property she owned in Ventura to John. He was questioned but subsequently released.

The second death was that of a 22-year-old girl. She was a student of the occult and at the time of her death she was helping John sell his books. It was rumored that the two had been lovers. She shot herself while in the vestibule of a local church–allegedly she was despondent over ill health. If John had played any part in her death it was never proved.

John flatly denied any knowledge of the drowned girl: “There is nothing to that story,” he said. According to him the story had originated at Patton State Hospital where he had been an inmate in 1920. He told investigators that the basis of the story was a play on his name. John explained that if you eliminated the first and fourth letters of his surname you were left with the word “lake”. Hmm. Really?

The hospital, originally known as Southern California Hospital for Insane and Inebriates, first opened its doors in 1893. Exactly why John had been confined in the hospital isn’t clear. At that time, and for many years after, it was a place where the seriously ill, or the seriously inconvenient, were confined. But he could have been there for any one of a number of issues–the place housed people suffering from mental disorders as well as physical ailments, specifically syphilis and other sexually transmitted diseases.

John’s immediate problem, and the one for which he was in legal trouble up to his eyeballs, was the contributing charge. He came face-to-face with Clara Tautrim and her mother, Caroline, in the anteroom of the District Attorney’s office. They, along with Cecyle Duncan, had given their statements to D.A. Buron Fitts and Deputy D.A. Joos. John didn’t appear to be distressed by the presence of his accusers. In fact when they left he turned to Detective Berenzweig and said: “Give me credit for picking good looking ones.”

Only Clara Irene Berry seemed to be upset. Clara admitted that she’d been a party to luring the Tautrim girl to John’s apartment, but she denied knowledge of John’s real intentions.

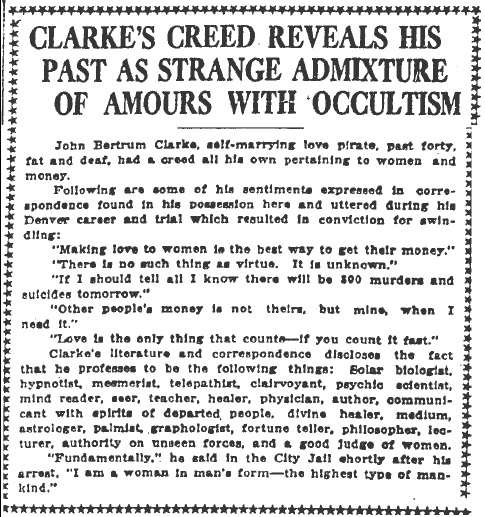

D.A. Fitts questioned John, but the accused couldn’t be persuaded to stay on topic. When he was asked how many women he’d had love affairs with he said: “Most of them didn’t keep their dates, but when they didn’t show up I went out and got another. What I wanted to do was get a wife. I didn’t care if I had to marry her sixteen times. I wanted to transfer over to her my patents which will soon be in use by the government and which will bring me in $3000 a day.” John was returned to his jail cell.

Los Angeles Times, July 21, 1924

John had several days’ growth of beard and was wearing the same soiled white suit when, on July 22nd, he was arraigned on the contributing charge. Clara Berry was arraigned as his accomplice. When she heard the charges against her she cried out: “No, no!”

While John and Clara were held in the county jail, each on $5000 bond, Chief Deputy District Attorney Buron Fitts held a press conference. He said: “The arrest of John Bertrum Clarke, ex-convict and former inmate of the asylum at Patton, undoubtedly removed a grave menace to the safety of the womanhood of Los Angeles. Under the guise of a minister of the Church of Cosmic Truth, Clarke planned in a systematic manner to prey on the girls and women of the city, evidence in our hands indicates. Neither the grey-haired woman nor the girl in her teens was immune from the menace. His conviction on a charge of contributing to the delinquency of a minor is of the utmost importance to this community, and anyone possessing information regarding the activities of the man should place it in our hands at the earliest possible moment. Detectives Berenzweig, Hoskins and Harris, as well as Captain Plummer and Lieutenant Littell of the vice squad, deserve the highest commendation for their clever and untiring efforts in bringing Clarke before the bar of justice. Men of Clarke’s stamp are as dangerous in every respect as the ‘bad man’ who seeks his victim with a gun. They are certainly not worthy the same respect.”

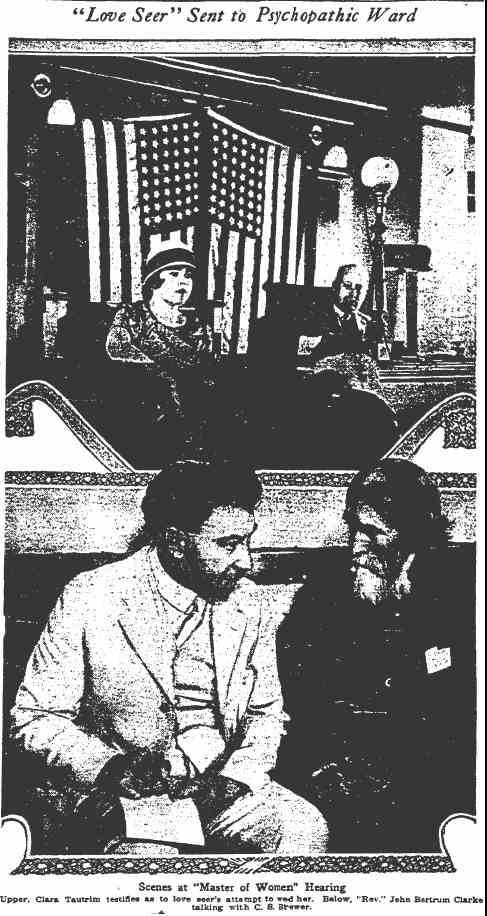

John’s sanity, or lack thereof, was to be determined by the Lunacy Commission (no, I didn’t make that up). They heard from Clara Tautrim who described her interactions with the so-called love-pirate. She told of his promises to make her a motion picture star, and she also told them about the time he had grabbed her and kissed on on the neck. An overture she didn’t appreciate.

A doctor who had examined John testified: “He has been quiet and cooperative, but talkative. He has an exalted opinion of himself. He said he has discovered an automatic alphabet which enables him to communicate with God. He told me he is one of the greatest spiritualists in the world. He boasted that he had saved 40,000 persons from becoming insane. He says that he has invented an automatic mail sorting machine that has a human mind, and that he wrote President Coolidge about it.”

Another doctor, named Carter, testified: “He (John) was in the Psychopathic Hospital in 1919. Then he was sent to Patton where he stayed one year. His present actions indicate that he did not thoroughly recover at Patton from hi mental illness. He has proven himself a menace to be at large regarding his annoyance of children and a menace to himself.”

“He is a thorough case of dementia praecox,” declared Dr. Allen.

John loudly reiterated his demand for a jury trial. However he was soon bound for the Patton Asylum where, on November 16, 1924, he picked the look on his door and escaped. LAPD and the Sheriff’s Department were keeping an eye on his usual haunts on the chance that he would return to the city. He never turned up.

In early April 1925 District Attorney Asa Keyes learned that John was in Reno; however there was no legal procedure in place to extradite an insane person. John may not have realized it but the Lunacy Commission had done him a favor. If he’d he gotten his wish of a jury trial he may have been found guilty and sentenced to prison. It would have been much more difficult to escape from San Quentin than it was from the Patton Hospital.

John was in the wind for months before being discovered in Reno. Several weeks after that he was under arrest in Seattle, Washington. Police Chief Severyns contacted the LAPD and District Attorney Keyes for advice.

The situation was the same as it had been when John had been found in Reno–he couldn’t be extradited. As long as John stayed away from Los Angeles he could continue to operate his crack-pot schemes and cons with impunity; at least until he ran afoul of the law elsewhere.

I’ve found copies of some of John’s writings, but I haven’t been able to track him any further than 1925. I’d love to know what happened to him. If anyone knows please share.

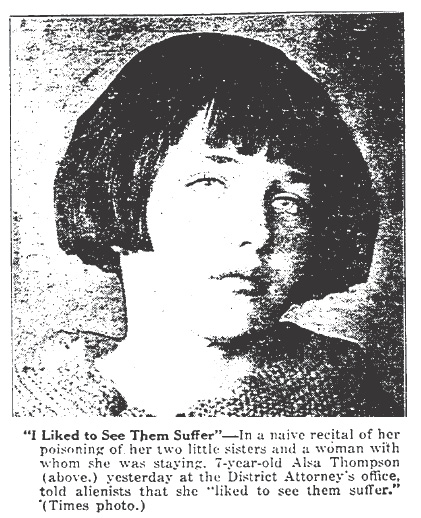

Russell Thompson refused to believe that his daughter, 7-year-old Alsa, had poisoned anyone. Dr. Edwin Huntington Williams, a psychiatrist, was inclined to agree with him. The doctor examined Alsa and pronounced her abnormal but “…not exactly insane.” He said: “It might be that in periods of epilepsy she has done strange things but it will take much careful observation to determine what is wrong with her. I have made only a casual examination but will make a more detailed one with Dr. Martin G. Carter, superintendent of the Psychopathic Hospital, and Dr. G.H. Steele, assistant superintendent.”

Russell Thompson refused to believe that his daughter, 7-year-old Alsa, had poisoned anyone. Dr. Edwin Huntington Williams, a psychiatrist, was inclined to agree with him. The doctor examined Alsa and pronounced her abnormal but “…not exactly insane.” He said: “It might be that in periods of epilepsy she has done strange things but it will take much careful observation to determine what is wrong with her. I have made only a casual examination but will make a more detailed one with Dr. Martin G. Carter, superintendent of the Psychopathic Hospital, and Dr. G.H. Steele, assistant superintendent.” Psychiatrists declared that Alsa was sane. Buron Fitts, the Chief Deputy District Attorney, didn’t seem to know what make of the girl. He said: “Frankly, I don’t know what to think. It’s the most extraordinary case I ever heard of. I don’t know whether to believe the child or not. Her stories sound improbable, but then there is the way she tells them. I just don’t what to think about it yet.”

Psychiatrists declared that Alsa was sane. Buron Fitts, the Chief Deputy District Attorney, didn’t seem to know what make of the girl. He said: “Frankly, I don’t know what to think. It’s the most extraordinary case I ever heard of. I don’t know whether to believe the child or not. Her stories sound improbable, but then there is the way she tells them. I just don’t what to think about it yet.”