Dolly McCormick witnessed the fatal shooting of Andrew “Andy” Kmiec by a man who had posed as a prospective buyer for Kmiec’s 1953 Mercury convertible. She was fortunate to have escaped with her life.

After she had directed deputies to the scene of Andy’s shooting, Dolly was transported to the Norwalk Sheriff’s Station to be interviewed by Lt. A.W. Etzel and Det. Sgt. Ned Lovretovich.

Det. Loveretovich first asked Dolly questions to establish her relationship to the deceased. She told the detective that she and Andy weren’t in a serious relationship, but they had been dating for about two months.

She said that Andy lived on Beverly Glen with a roommate, Alex Milne, and the two men appeared to get along well. As far as she knew Andy didn’t have any enemies, despite what his killer had said about having been hired to do away with him.

Neither Andy nor Dolly were California natives — Andy’s car still bore Indiana license plates, and Dolly had only recently moved to North Hollywood from Prairie Grove, Arkansas to live with her cousin, a television advertising executive. Andy had come to Southern California during WWII and, like thousands of other veterans, decided to make it his permanent home a few years later. Dolly, too, was looking for a life different than the one she’d had in Arkansas.

Andy Kmiec was described by his employer, friends, and acquaintances as a decent guy, liked by everyone who knew him. Det. Lovretovich couldn’t find anyone who had even disliked Andy, let alone hated him enough to hire someone to kill him.

Dolly was questioned in detail about the events of the evening of the slaying from the moment that Andy arrived in North Hollywood to pick her up for their date.

On the drive downtown to the Biltmore Hotel, Andy told Dolly:

“This is sort of an odd situation. I have never heard of a

business transaction carried on this way.”

When they arrived at the Biltmore, Andy asked Dolly to wait in the car while he went into the hotel to find the prospect. He arrived a few minutes later and introduced Dolly to the stranger — but she couldn’t recall the man’s name.

She described him to Det. Loveretovich as being approximately 45-50 years old, about 5′ 10″, with blondish brown hair. He was wearing a tan suede jacket with knit ribbing at the collar and cuffs and tan pants. She said the man needed a shave badly, but that he was otherwise unremarkable. He was wearing a pair of gold metal, rimless, bifocal eye glasses.

Dolly became uncomfortable during the drive to Whittier because the stranger told conflicting stories about his employment. He had first implied that he owned a pottery

business in Santa Ana, then moments later said he was the plant’s supervisor. What really alarmed Dolly was when the man seemed unable to provide concise directions to his own home.

The pretty sales clerk went on to describe what happened after the man had told Andy to park the car. She said that he produced a gun, showed it to Andy and said:

“You know what this is.”

Andy said yes, of course he knew that it was a gun — then he offered the stranger his wallet, the car, anything if he would leave.

The stranger said that he’d been hired to “take care” of Andy, and that he was being well paid for the job.

Andy continued to plead, but the man forced him into the back seat of the Mercury at gun point. Dolly was made to drive the car with the stranger sitting next to her.

Right before they pulled to a stop the man said to Dolly:

“It’s too bad that you had to be an innocent bystander, but as long as you do what I tell you to do I promise I won’t hurt you.”

Suddenly the man leaned over into the back seat and fired — Dolly heard Kmiec gasp, and then saw him clutch his chest. The man fired again and Dolly jumped out of the car. She felt something tug on the belt of her dress but she didn’t know if it was the assailant or if she’d caught it on the door handle. The belt ripped away from her dress as she scrambled to get away.

Dolly had left behind her in the car a black, faille purse with a gold clasp, her coat, and a Cosmopolitan magazine.

Once she got to intersection of Lakeland and Painter she flagged down a a passing motorist. She got into the car and said:

“A man’s just been shot. Will you take me to the police, or some place where I can call the police, as quickly as possible?”

She was taken to a drug store where she phoned the Sheriff’s Department.

Det. Lovretovich gleaned what he could from Dolly’s statement, but it wasn’t much. He had a description of the killer, which could fit thousands of men in Los Angeles, and a description of the weapon, which appeared to have been a revolver with a long barrel. The only decent physical evidence was a pair of eye glasses found at the scene and, if they were lucky, they might be able to ID fingerprints left in blood.

Alex Milne, Andy’s roommate, was the next to be questioned by Det. Lovretovich. Alex said he was employed as a test pilot by Lockheed in Burbank. He’d known Andy for about ten months and they had been rooming together in a house on Beverly Glen for a few months prior to the murder.

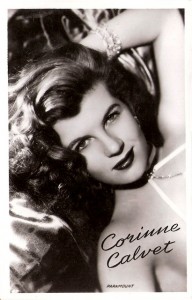

From his interview it was clear that Alex was the quintessential ’50s swinging bachelor. He dropped the names of a few of his actor friends like Don Haggerty, and John Bromfield and his wife Corrine Calvert. He seemed like a guy who wanted to make an impression.

When asked if they ever had any arguments, Alex said that he and Andy got along fine. Det. Lovretovich wanted to know if he and his roommate ever went out with the same girls. Alex admitted that they had, but it was not a big deal. He told Ned that he’d fixed Andy up a few times with women he’d previously dated — he even shared that Andy had “made the team” a couple of times with some of them. Of course those girls were simply “pieces of ass” as far as Alex was concerned. When Det. Lovretovich asked if the women were hustlers, Alex said no, they were airline stewardesses!

After learning more than he probably ever wanted to know about Alex’s social life, Ned Lovretovich and the others assigned to the case continued to follow-up every lead, trying to get a break.

After learning more than he probably ever wanted to know about Alex’s social life, Ned Lovretovich and the others assigned to the case continued to follow-up every lead, trying to get a break.

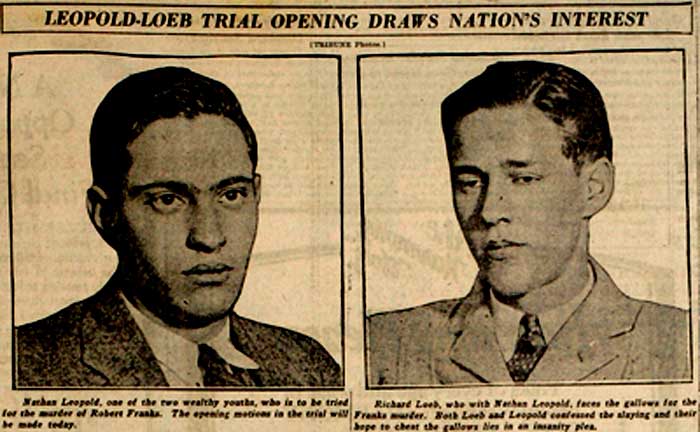

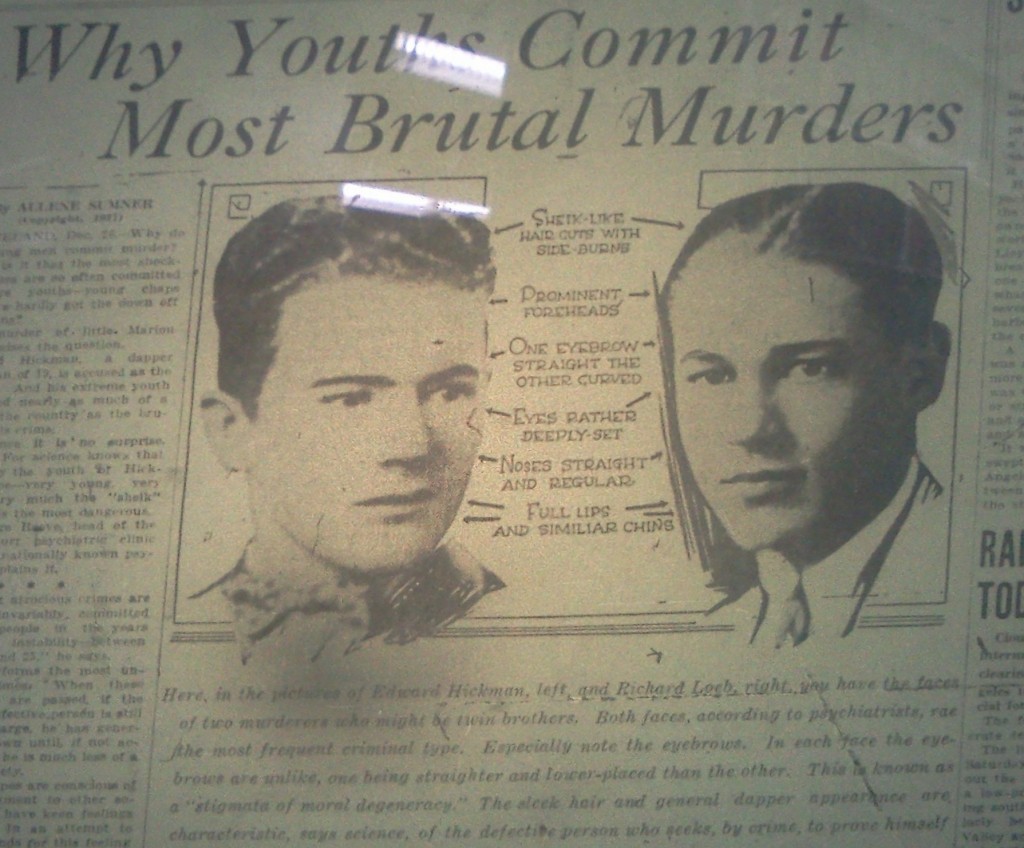

Detectives hoped that the bloody eye glasses found at the scene would crack the Kmeic case, just as a pair of specs had lead Chicago cops to Nathan Leopold and Richard Loeb in 1924. Leopold and Loeb were convinced they’d committed the perfect crime, a thrill killing, when they murdered 14 year old Bobby Franks. The prescription eye glasses proved them wrong.

As Sheriff’s investigators continued to probe for answers, Andy Kmiec’s body was sent by air to East Chicago, Indiana, for burial.

As it turned out, Andy Kmiec’s killer wouldn’t be identified by his eye glasses, but rather by the sharp eyes of a Sheriff’s records clerk.

NEXT TIME: The Sheriffs make an arrest in Andy Kmiec’s murder.

![Welby Hunt and William Hickman [Photo is courtesy of LAPL.]](https://derangedlacrimes.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/01/00027806_HICKMAN_HUNT-300x285.jpg)