On December 26, 1927 on a train taking him from Pendleton, Oregon to Los Angeles William Edward Hickman confessed to the senseless slaughter of twelve year old school girl, Marion Parker. He told District Attorney Keyes, Chief of Detectives Cline, and Chief of Police Davis that “I am ready to talk. I want to tell the whole story.” The cops said later that Hickman seemed to enjoy recounting details of the kidnapping, murder, and dismemberment.

On December 26, 1927 on a train taking him from Pendleton, Oregon to Los Angeles William Edward Hickman confessed to the senseless slaughter of twelve year old school girl, Marion Parker. He told District Attorney Keyes, Chief of Detectives Cline, and Chief of Police Davis that “I am ready to talk. I want to tell the whole story.” The cops said later that Hickman seemed to enjoy recounting details of the kidnapping, murder, and dismemberment.

Hickman admitted that he’d had no accomplice. He said that his motive for the kidnapping was to get $1500 to go to college, he claimed he wanted to go to bible school. And his motive for killing Marion? Hickman said : “I was afraid she would make a noise.” He had murdered her the day following the kidnapping.

The story Hickman told was beyond comprehension. He said that he had killed Marion by strangling her with a towel. He had knotted it around her throat and pulled it tightly for two minutes before she became unconscious. Once Marion was out, Hickman took his pocket knife and cut a hole in her throat to draw blood. He took her to the bathtub and drained her body of blood.

He cut each arm off at the elbow, and her legs at the knees. Her put her limbs in a cabinet. He removed Marion’s clothing and cut through her body at the waist. At some point during the mutilations he realized that he would lose the ransom he’d demanded if he wasn’t able to produce the kidnapped girl when he arrived at the rendezvous with her father. He wrapped the exposed ends of her arms and waist with paper. He combed her hair, powdered her face and then with a needle and thread he sewed open her eyelids. He wanted to give Perry Parker the illusion that his little girl was still alive.

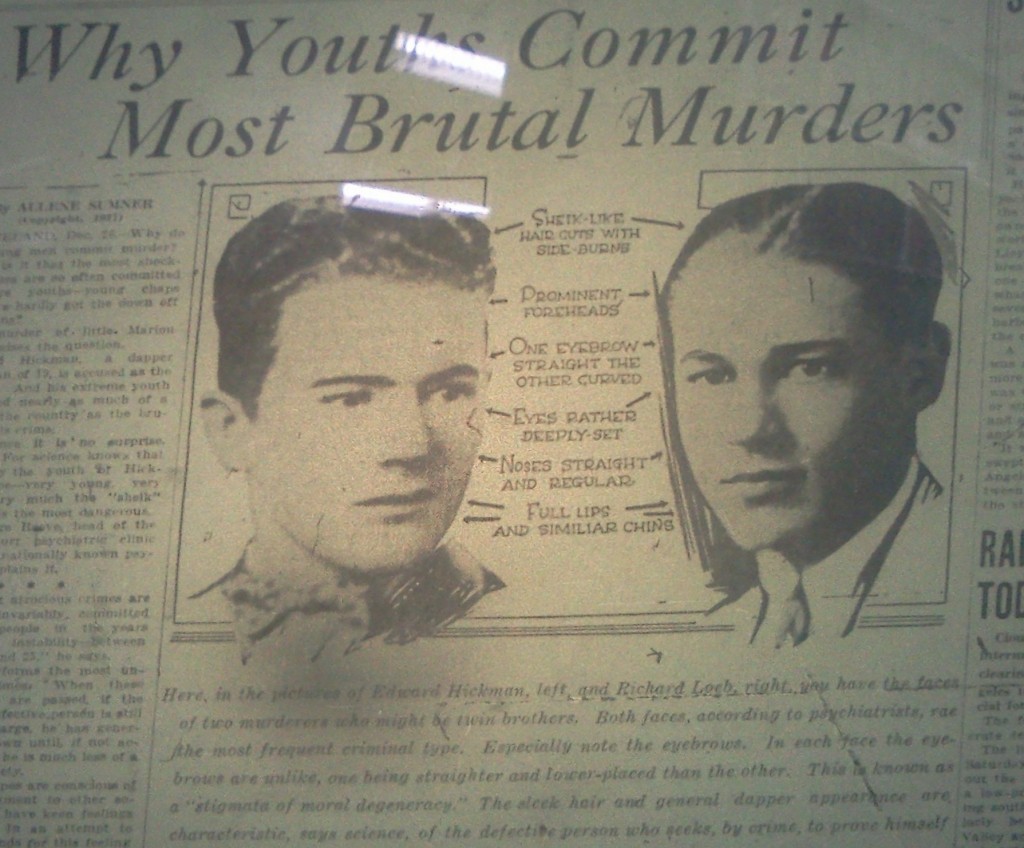

Local newspapers became obsessed with youthful perpetrators — Hickman was only nineteen. The Record (where Aggie Underwood was watching the case against The Fox unfold) published a photo of Hickman alongside one of Riichard Loeb under the headline: “Why Youths Commit Most Brutal Murders”.

The photos of Hickman and Loeb compared their features in an attempt to reveal the outward signs of a homicidal youth. The two young men look nothing alike to me, but that didn’t keep The Record from stating that their “sheik-like hair cuts with side burns, prominent foreheads, deep-set yes, straight and regular noses, and full lips with similar chins” were signs of a killer. In particular the eyebrows of the young men were described as “one being straighter and lower placed than the other” which, said The Record, was known as a “stigmata of moral degeneracy”!

The photos of Hickman and Loeb compared their features in an attempt to reveal the outward signs of a homicidal youth. The two young men look nothing alike to me, but that didn’t keep The Record from stating that their “sheik-like hair cuts with side burns, prominent foreheads, deep-set yes, straight and regular noses, and full lips with similar chins” were signs of a killer. In particular the eyebrows of the young men were described as “one being straighter and lower placed than the other” which, said The Record, was known as a “stigmata of moral degeneracy”!

Richard Loeb was one of a pair of teenage wanna be Nietzschean supermen (his accomplice was Nathan Leopold) who, in 1924, kidnapped and murdered fourteen year old Robert “Bobby” Franks in Chicago. People around the country were horrified that two young men, both of whom came from wealthy families, could commit murder based on their belief that they were superior beings and, as Leopold had written to Loeb: “…exempted from the ordinary laws which govern men.”

The teenagers must have been shocked to discover that they were not exempted from ordinary laws. In fact, the two killers would have paid for the crime with their lives if not for their attorney Clarence Darrow. Darrow’s only mandate was to save them from execution, and in that he was successful.

While Hickman was being tried for Marion Parker’s murder, he was also being investigated for a series of pharmacy robberies, one of which had ended in the cold-blooded killing of druggist Ivy Thoms on December 24, 1926. Sixteen year old Welby Hunt was eventually identified as Hickman’s accomplice and he promptly confessed to his part in the fatal drugstore robbery. His confession saved him from hanging. Nothing would save The Fox.

Hickman didn’t have the same advantages as Leopold and Loeb, and he wasn’t represented by Clarence Darrow. He was, according to the district attorney, “…certain to hang”. Hickman was one of the first in the state to try the newly established plea of not guilty by reason of insanity, but the jury didn’t buy it. They knew he was evil, but that wasn’t the same thing as being insane.

On February 14, 1928 The Record put out an extra edition with the headline ‘Fox to Hang on April 27″. Hickman and Hunt were each found guilty for the robbery/homicide and each was given a life sentence. The robbery/homicide trial and the inevitable appeals on his death sentence for Marion Parker’s murder delayed Hickman’s date with the hangman, but only for a few months.

On October 19, 1928 at San Quentin, William Edward Hickman was taken to the gallows where he fainted as the black hood was placed over his head. According to reports his body sagged and fell sideways He was unconscious when the hangman raised his hand and three men with poised knives behind a screen on the gallows platform drew the blades simultaneously across three strings. One of the strings released the trap and Hickman slipped through. It took fifteen minutes for him to die. There was a dispute over whether his shortened plunge caused his neck to break, or if he had strangled to death — as Marion Parker had done less than a year before.

On October 19, 1928 at San Quentin, William Edward Hickman was taken to the gallows where he fainted as the black hood was placed over his head. According to reports his body sagged and fell sideways He was unconscious when the hangman raised his hand and three men with poised knives behind a screen on the gallows platform drew the blades simultaneously across three strings. One of the strings released the trap and Hickman slipped through. It took fifteen minutes for him to die. There was a dispute over whether his shortened plunge caused his neck to break, or if he had strangled to death — as Marion Parker had done less than a year before.

![Welby Hunt and William Hickman [Photo is courtesy of LAPL.]](https://derangedlacrimes.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/01/00027806_HICKMAN_HUNT-300x285.jpg)