Los Angeles has been home to some of the wiliest and most wicked criminals in the world. And where there are criminals there are attorneys to defend them. I’ll leave it to you to decide which group is worse.

Among the defense attorneys who practiced in the city, one of the most fascinating was Samuel Simpson Hahn. Known as S.S. Hahn, which makes him sound like a luxury liner, Hahn was born Schrul Widelman on September 18, 1888 in Ternova, Besarubia, Russia. He is believed to have arrived in the U.S. on June 30, 1906 and changed his name to Samuel Needleman. Contrary to the persistent belief that xenophobic immigration agents arbitrarily changed the names of newcomers many people opted to change their surnames to adapt to their new lives in America. In any case, by 1912 the newly minted Samuel Needleman had moved to Los Angeles and had changed his name one last time. He became Samuel Simpson Hahn. That moniker stuck with him for the rest of his life.

![S.S. Hahn with a witness in Aimee Semple McPherson's trial. [Photo courtesy of LAPL]](https://derangedlacrimes.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/00021982_hahn_witness-in-McPherson-trial.jpg)

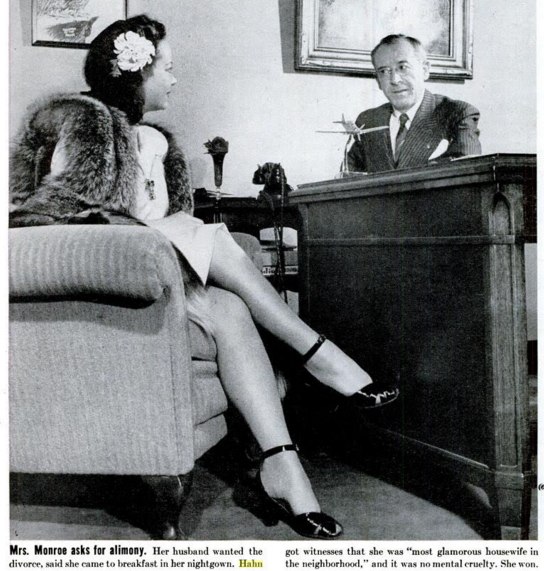

S.S. Hahn with a witness in Aimee Semple McPherson’s trial. [Photo courtesy of LAPL]

On July 22, 1915, having passed his exam, Samuel Hahn was admitted to the California State Bar and for the next four decades he defended some of the most notorious criminals in the city. Hahn’s client list reads like a Who’s Who of local crime. Among those who sought his services were serial killer Louise Peete and naughty evangelist Aimee Semple McPherson.

Hahn didn’t limit his practice to felons. Following WWII there was a sharp uptick in divorces. Starry-eyed couples who married in the heat of passion during wartime found themselves dreading the prospect of thousands of dreary days in each other’s company. In 1945, LIFE Magazine featured Hahn in an article on divorce mills. Interestingly, he appears to have met his second wife, Mary Monroe, when she came to him to dissolve her marriage.

I intend to write more about S.S. Hahn in the coming months. I find his career worthy of multiple posts. He was disbarred as a young attorney in the 1910s, possibly for suborning perjury, but appears to have won an appeal to restore his license. His death by drowning in a backyard swimming pool in 1957 was ruled a suicide, but it was highly suspicious. I’ll get to more of Hahn’s life later—I think you’ll find it compelling.

Today I’m going to cover a 1934 case from the Hahn files in which he defended a man accused of murdering his wife.

Shortly before midnight on Wednesday, June 27, 1934, Mr. and Mrs. Frank Kilborane of 4919 Bemis Street were driving on a lonely stretch of dirt road between the Southern Pacific tracks and the Los Angeles River. They were about 200 feet West of the intersection of San Fernando Road and Colorado Boulevard when they noticed a car. It isn’t clear what caught the attention of the couple but they decided to investigate. They found a woman sitting upright and dead on the passenger side. Seated next to her behind the steering wheel was a man. He was severely wounded and semi-conscious. Both had suffered gunshot wounds to the head.

Police identified the victims as Gray (Grey) Everett McNeer and his estranged wife, Beatrice (Betty) Helene Harker McNeer. While fighting for his life in the General Hospital Gray managed a brief statement in which he laid the blame for the shootings on his dead wife. Unfortunately for Gray the physical evidence suggested a far different scenario.

Police identified the victims as Gray (Grey) Everett McNeer and his estranged wife, Beatrice (Betty) Helene Harker McNeer. While fighting for his life in the General Hospital Gray managed a brief statement in which he laid the blame for the shootings on his dead wife. Unfortunately for Gray the physical evidence suggested a far different scenario.

There were a couple of major problems with Gray’s statement. First, Betty had been shot three times in the head and second, she was right handed. Even a contortionist would have found it difficult to shoot herself on the left side of her head if she was right handed. Besides, if Betty was the shooter why would she leave her intended victim moaning and alive? Wouldn’t she have made certain he was dead before she turned the gun on herself—three times? Detectives were convinced Gray was a killer and placed him in the prison ward of the hospital—not that he was capable of taking it on the lam. Doctors weren’t convinced that he would make it through the night.

With Gray in the hospital, Detective Lieutenants Sanderson and Hill of the police department began their investigation into the backgrounds of the McNeers.

With Gray in the hospital, Detective Lieutenants Sanderson and Hill of the police department began their investigation into the backgrounds of the McNeers.

At 33 years of age Gray already had an extensive criminal record. The 1930 Federal Census lists Gray as an inmate in the Oklahoma State Penitentiary where he was a machine operator in the pants factory. He was in prison for his part in the robbery of a paper company in Oklahoma City. If his life since his release from prison was any indication of his future plans he had no intention of going straight, ever. At the time of the shooting Gray was wanted for questioning in a recent string of robberies in Los Angeles.

Betty was 29 when she died and she had been married and divorced twice before she tangled with Gray. She was 19 when she married a wealthy Altadena inventor, E.P. Pottinger. They divorced after two years and Betty wed Arthur Nollau who owned a knitting mill at 1409 West Washington Boulevard. The marriage to Nollau also lasted roughly two years. Twenty-four months seemed to be limit of Betty’s attention span for marriage. In the days prior to her death she had filed for divorce from Gray to whom, you guessed it, she had been married for approximately two years.

Gray’s condition appeared to be improving; which meant that the ex-con would likely be indicted for his wife’s murder. In that case he would require the services of an attorney.

NEXT TIME: Justice Times Two continues.

1901