Three alienists, Drs. Benjamin Blank, Victor Parkin and Paul Bowers, were called on to determine Gray McNeer’s sanity. The doctors testified at a sanity hearing on October 29, 1934. They said that they had examined Gray and found him to be sane. The jury concurred. Gray’s trial for Betty’s murder would resume despite his loud and incoherent courtroom outbursts.

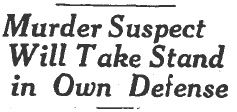

The day following Gray’s sanity hearing, S.S. Hahn announced that his client would take the stand in his own defense. Putting Gray on the stand was a risky move. If he was incapable of controlling himself at the defense table, how would he fare on the witness stand? On more than one occasion the trial had to be adjourned because Gray became hysterical. How would Gray, still swathed in bandages and wheelchair bound, comport himself under cross examination?

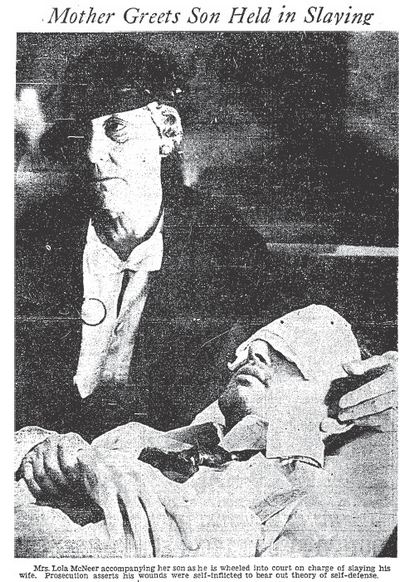

Gray was scheduled to take the stand on November 2nd but he was too ill to appear in court. The trial was delayed for a few days until it was decided that if Gray couldn’t come to court, the court would come to him. The trial resumed at Gray’s bedside in the County Jail Hospital.

Gray was scheduled to take the stand on November 2nd but he was too ill to appear in court. The trial was delayed for a few days until it was decided that if Gray couldn’t come to court, the court would come to him. The trial resumed at Gray’s bedside in the County Jail Hospital.

Gray testified that on the night of the Betty’s death he met her at the apartment of a mutual friend, Lucille Herner, and then they drove to an isolated spot in Glendale where they argued. It was in the midst of their argument, Gray said, that Betty pulled out a gun. He said he felt a heavy blow to his head and then didn’t remember a thing until he regain consciousness in the Glendale Police Station. It was there that he was informed that his Betty’s body had been found in the car next to him.

The remainder of the trial was conducted in the hospital with Dr. Benjamin Blank in constant attendance to monitor Gray’s condition. The case went to the jury late on November 7th. At 10 p.m., after hours of deliberation, the jury was sequestered for the night.

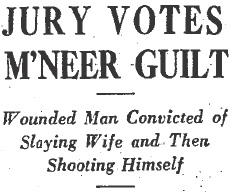

On the evening of November 8th the jury returned with their verdict. They found Gray guilty of second degree murder. Gray began to babble incoherently, but settled down after a reprimand from the judge. Gray’s mother, Lola, said she had no plan to appeal the verdict. S.S. Hahn said, “Mrs. McNeer is convinced that her son’s condition is such that the probably will not live to serve his sentence.” The doctors disagreed. They believed Gray would recover from the bullet wound.

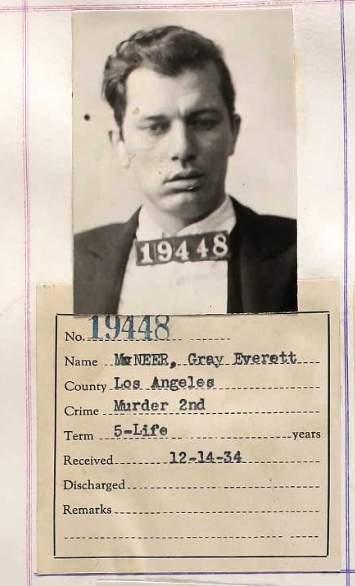

Gray was taken to Folsom Prison to begin serving his sentence of from 5 years to life. Gray’s mother said there was no plan to file an appeal. But plans change.

Gray was taken to Folsom Prison to begin serving his sentence of from 5 years to life. Gray’s mother said there was no plan to file an appeal. But plans change.

The bullet in his head was removed by San Quentin physicians, so Gray was in much better shape for his second trial than he had been for the first go ‘round.

In Judge Vicker’s court, Gray’s second trial began with testimony from police chemist Ray Pinker. Pinker testified that powder burns on Betty’s arms indicated that she was directly in front of the gun at the time the fatal shot was fired into her head. The powder burns were not consistent with a suicide.

Gray took the stand on November 21st. He reiterated the story he had told at his first trial. Gray said that he and Betty had taken an automobile ride and attempted reconciliation. When she refused to return to him Gray said he suggested divorce. According to Gray, Betty became angry, pulled out a gun and shot him in the head. He said even though he was gravely wounded he struggled with Betty for possession of the weapon. He lost the struggle and,that’s when Betty turned the gun on herself.

The trial was going along smoothly until Deputy District Attorney Wildey asked Gray to repeat a conversation he’d had with Betty right before the shooting. Gray snapped: “I will not repeat it. It’s all cut and dried. Go ahead and shoot what you have. I refuse to testify further in this case!” Gray then grabbed his crutch and hobbled away from the witness stand, ignoring the judge’s order to answer the question. That was it for Gray. He didn’t take the stand again.

The case went to the jury of six men and six women who, just as the jury in the first trial, had to be sequestered.

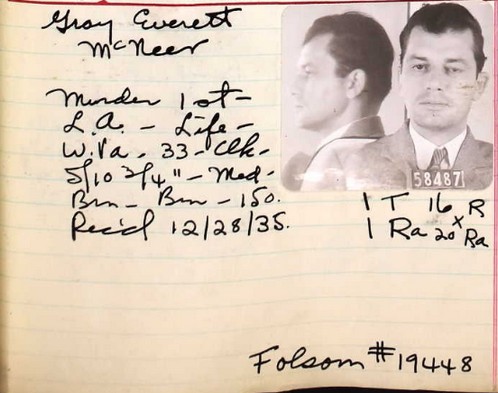

When the jury returned, Gray was found guilty of first degree murder and sentenced to life in prison. He’d rolled the dice on a second trial and come up snake eyes. His second sentence was harsher than the first.

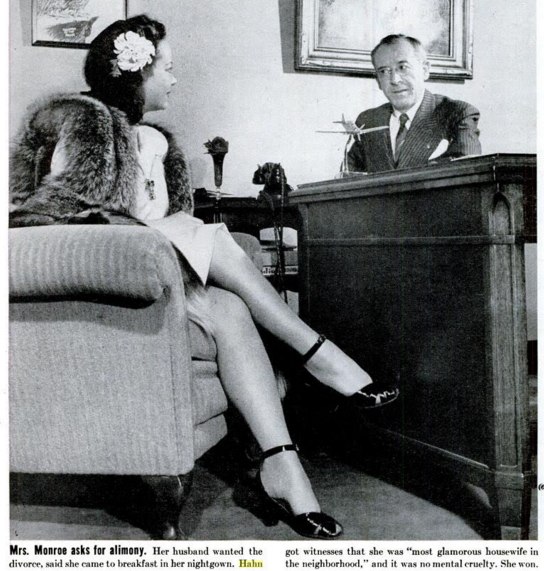

In 1958, after 24 years in prison, Gray appealed again on the grounds of double jeopardy. The plea was rejected. Shortly afterwards he sought legal relief via habeas corpus. He wasn’t represented by S.S. Hahn because Hahn had died mysteriously in the swimming pool at his son’s cabin in Castaic. The two public defenders representing Gray were successful and he was ordered returned to Los Angeles for re-sentencing for the crime of second degree murder. I haven’t been able to find out what happened at the re-sentencing hearing.

Gray Everett McNeer died in Sacramento on July 27, 1964.

NOTE: I’m going to try to find out what happened to Gray. If any of you find anything please let me know!

UPDATE 5/29/2017: Many thanks to a reader, Katie, for letting me know that Gray McNeer committed suicide in Folsom prison in 1964. With her information I found the following paragraph from the Long Beach Independent dated July 28, 1964:

Gray’s mother, Lola, remained at her son’s bed side and on August 24th it was reported that she had given her official consent for an operation to remove the bullet from his brain. It isn’t clear why a man in his 30s would need his mother’s consent, but it may have been that he was in no condition to give it himself. S.S. Hahn told the court that in his present condition Gray was in imminent danger of death and that, even if he survived, he might be become “an imbecile.” The operation was given odds of 100 to 1 that it would succeed; but it was Gray’s only hope.

Gray’s mother, Lola, remained at her son’s bed side and on August 24th it was reported that she had given her official consent for an operation to remove the bullet from his brain. It isn’t clear why a man in his 30s would need his mother’s consent, but it may have been that he was in no condition to give it himself. S.S. Hahn told the court that in his present condition Gray was in imminent danger of death and that, even if he survived, he might be become “an imbecile.” The operation was given odds of 100 to 1 that it would succeed; but it was Gray’s only hope. Hahn objected to the Judge’s admonition and there was a short recess. Once back in the courtroom, Judge Burnell spoke to the jury: “Ladies and gentlemen of the jury, I am making this statement to you at the suggestion and with the consent of counsel for both sides, the People and the defendant. You, of course, could not help but observe the fact yesterday afternoon that the defendant was making more or loess noise, talking and groaning, and the Court made some remarks about ceasing the theatricals, or something of that sort. That, of course, is something that you haven’t any business to pay any attention to, and I want you to entirely disregard it. The defendant is here on trial for one specific offense, and all the jury have any right to consider whatever is the evidence in the case and nothing else. I know you will appreciate that and be able to do that, but for your information, in view of the apparent condition of the defendant, I am trying now to get hold of Dr. Blank, the jail physician, to come down here and tell us whether he thinks from his examination of the defendant there is any reason why the case should not continue. In other words, whether or not the defendant is in a condition physically and mentally that will preclude going ahead with the trial. Until we hear from Dr. Blank, we will go ahead, and if there is any demonstration on the part of the defendant, you will disregard it. You are not here to try anything except the facts in this case.”

Hahn objected to the Judge’s admonition and there was a short recess. Once back in the courtroom, Judge Burnell spoke to the jury: “Ladies and gentlemen of the jury, I am making this statement to you at the suggestion and with the consent of counsel for both sides, the People and the defendant. You, of course, could not help but observe the fact yesterday afternoon that the defendant was making more or loess noise, talking and groaning, and the Court made some remarks about ceasing the theatricals, or something of that sort. That, of course, is something that you haven’t any business to pay any attention to, and I want you to entirely disregard it. The defendant is here on trial for one specific offense, and all the jury have any right to consider whatever is the evidence in the case and nothing else. I know you will appreciate that and be able to do that, but for your information, in view of the apparent condition of the defendant, I am trying now to get hold of Dr. Blank, the jail physician, to come down here and tell us whether he thinks from his examination of the defendant there is any reason why the case should not continue. In other words, whether or not the defendant is in a condition physically and mentally that will preclude going ahead with the trial. Until we hear from Dr. Blank, we will go ahead, and if there is any demonstration on the part of the defendant, you will disregard it. You are not here to try anything except the facts in this case.”![S.S. Hahn with a witness in Aimee Semple McPherson's trial. [Photo courtesy of LAPL]](https://derangedlacrimes.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/00021982_hahn_witness-in-McPherson-trial.jpg)

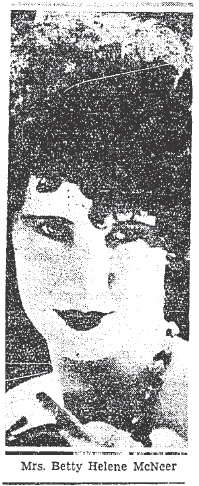

Police identified the victims as Gray (Grey) Everett McNeer and his estranged wife, Beatrice (Betty) Helene Harker McNeer. While fighting for his life in the General Hospital Gray managed a brief statement in which he laid the blame for the shootings on his dead wife. Unfortunately for Gray the physical evidence suggested a far different scenario.

Police identified the victims as Gray (Grey) Everett McNeer and his estranged wife, Beatrice (Betty) Helene Harker McNeer. While fighting for his life in the General Hospital Gray managed a brief statement in which he laid the blame for the shootings on his dead wife. Unfortunately for Gray the physical evidence suggested a far different scenario. With Gray in the hospital, Detective Lieutenants Sanderson and Hill of the police department began their investigation into the backgrounds of the McNeers.

With Gray in the hospital, Detective Lieutenants Sanderson and Hill of the police department began their investigation into the backgrounds of the McNeers.