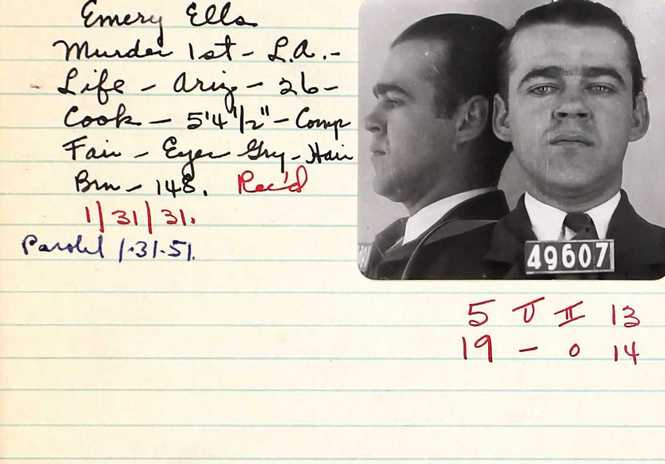

Emery Ells

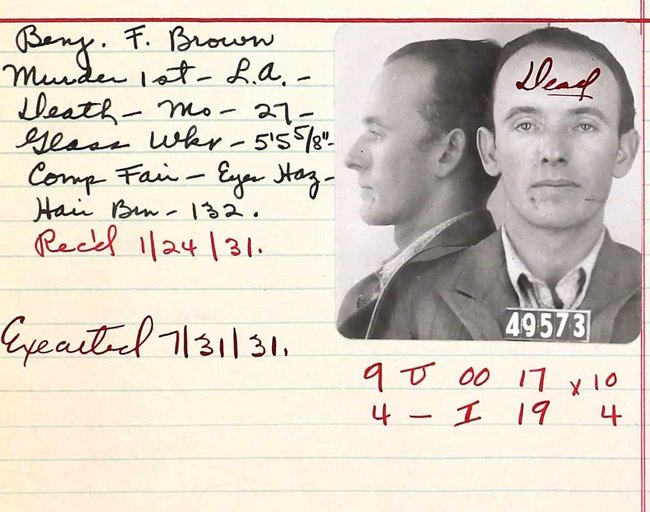

From his jail cell, Emery Ells maintained his innocence in the shotgun slaying of his ex-wife, Merle. Under questioning he gave up the names of several of his acquaintances. One of the men he named was 27-year-old glass-blower, Benjamin J. Brown.

Shortly after midnight on on November 5, 1930, LAPD Detective Lieutenants Filkas and Baggott arrived at Benjamin’s home at 2575 1/2 Randolph Street in Huntington Park. They later said that they were there “on a hunch” that he might have some information that would enable them to break Emery’s alibi.

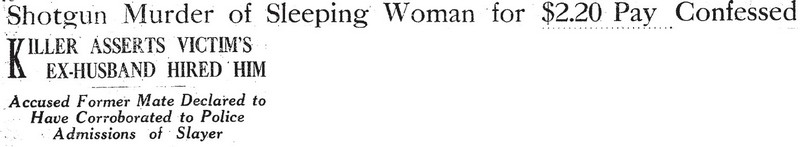

The detectives saw that Benjamin was nervous, and felt he had something to hide. He proved them correct by telling conflicting stories for over an hour before he suddenly slumped down in his chair and confessed. What did he have against the dead woman? According to Benjamin he’d never even met her before he unloaded a single barrel of the shotgun at her, and he had no idea that she was Emery’s ex-wife. He’d been hired by Emery to kill a woman who was allegedly ruining a baby’s life. As down payment he was given $2.20 in dimes. A full payment of $2,000 would be his when the job was done.

Knowledge of Benjamin’s confession, and his naming of Emery as the mastermind, was kept secret for hours until after detectives walked him through each step along the way to Merle’s brutal death. Benjamin told detectives that Emery had taken him to his brother Alfred’s home on Elizabeth Street and it was there that he was given a shotgun, gloves, flashlight, and a revolver. Emery advised Benjamin to “…use the gloves to prevent leaving any fingerprints and to use the revolver for my own protection afterward.”

Merle spent the last night of her life on a date. Benjamin spent that night preparing to kill her. He said: “Saturday night I took the ‘rod’ and went out and stuck up a guy and took his care away from him. I drove the car home, I got the guns and stuff and drove to the house where the woman was staying. Ells had gone out with me a day or so before and pointed out to me and also told me just where she would be sleeping on the porch.”

Merle spent the last night of her life on a date. Benjamin spent that night preparing to kill her. He said: “Saturday night I took the ‘rod’ and went out and stuck up a guy and took his care away from him. I drove the car home, I got the guns and stuff and drove to the house where the woman was staying. Ells had gone out with me a day or so before and pointed out to me and also told me just where she would be sleeping on the porch.”

“I left the car parked in front and walked around to the porch. I had a pass key but the door was unlocked so I just pushed it open. She was lying in bed. My idea was not to hurt the kid. Ells had told me now to hurt the boy.”

Benjamin fainted. Cops revived him and he continued: “So I wanted her to sit up. I said to her, ‘wake up Merle. I want to speak to you outside quick. But she didn’t sit up.”

“Did she speak to you, say anything?” asked Filkas.

“She just whispered something–something like ‘what’s the matter.’ or like that.”

“You fired the shot then?” queried Filkas.

“No, I lost my nerve. I went back out and got in the car and drove around for a long while. Finally I got calmed down and went back again. I left the car in the same place again and went to the porch. But when I opened the door I again lost my nerve and went back and sat in the car. I got to thinking and decided I’d have to get it done quick so I went back to the porch a third time.”

“The door, I opened it and that was that, only one barrel.”

Detective Filkas and the others thought that Benjamin was going to pass out again, but he remained upright. He took a breath, and resumed his story.

“Well, anyhow you know that much of it. I was surprised I didn’t make any m ore noise myself. But I got out. I dropped the gun but held onto the flashlight. Then I got back into the car and I drove it just as fast as it would go. Just after I started, about a block away, an officer yelled to me to turn on my lights.”

After the shooting, Benjamin went home where he hid the revolver, gloves and part of his clothing in an adjoining vacant house. He abandoned the car in Huntington Park. All he had left to do was to inform Emery that the job was done and collect his blood money.

“I went to Emery where he was working in the cafe and told him that the job was done. He said another guy had the money for me. I told him to hurry up and get the cash for me quick, and he said O.K. I gave him the flashlight and revolver.”

The flashlight was discovered by Detective Lieutenant Savage in a search of Alfred Ell’s car. It was behind a cushion where Emery had shoved it during the ride home from the cafe following his shift on Sunday morning.

Captain Davidson and detectives at Central Station arranged for a dramatic, and meticulously choreographed, face-to-face meeting between the co-conspirators. Emery still didn’t know Benjamin had confessed when he was taken into the Captain’s office. When he entered the room he saw the gloves and clothes worn by Benjamin sitting on a table. Next to them sat the revolver, shotgun, and flashlight. He stopped to take it all in. His hands began to shake.

The investigators were silent in that ominous, “I know what you did” way that that all law enforcement officers seem to master. Their j’accuse look was more debilitating than a punch in the stomach. Captain Davidson didn’t speak, he merely looked at Emery and then pointed to the evidence on the table. Moments later, Benjamin was led into the room. He and Emery exchanged glances and nodded at each other. It was Emery’s turn to confess.

An hour later Captain Davidson came out of his office and announced: “Ells has made a complete confession of the whole thing. His statement corroborates in nearly every detail, except the actual killing, that of Brown.”

There was one thing that had puzzled the detectives about the night of the killing–why hadn’t Merle’s sister and brother-in-law heard anything? And how had Benjamin avoided killing the child? Apparently the baby had awakened during the night and gone into his aunt and uncle’s room to sleep. Their bedroom was separated from the glassed-in porch/abattoir by several other rooms. In the morning when the boy went to rouse his mother he became covered in her blood, and it was then that he ran screaming for help.

The confessions were exactly what the D.A. wanted–of course there is never a guaranteed outcome in a jury trial.

NEXT TIME: The Dime Murder trial and wrap-up.

Benjamin confessed to police, but his trial was postponed until January 1931. His attorneys needed time to gather evidence regarding his sanity.

Benjamin confessed to police, but his trial was postponed until January 1931. His attorneys needed time to gather evidence regarding his sanity. Emery’s trial lasted two weeks. On January 8, 1931 after deliberating for just a few hours the jury found him guilty of first degree murder. They recommended life in prison rather than the death penalty asked for by the prosecution. When Emery heard that his life had been spared he turned to his attorney and grinned.

Emery’s trial lasted two weeks. On January 8, 1931 after deliberating for just a few hours the jury found him guilty of first degree murder. They recommended life in prison rather than the death penalty asked for by the prosecution. When Emery heard that his life had been spared he turned to his attorney and grinned.

Merle spent the last night of her life on a date. Benjamin spent that night preparing to kill her. He said: “Saturday night I took the ‘rod’ and went out and stuck up a guy and took his care away from him. I drove the car home, I got the guns and stuff and drove to the house where the woman was staying. Ells had gone out with me a day or so before and pointed out to me and also told me just where she would be sleeping on the porch.”

Merle spent the last night of her life on a date. Benjamin spent that night preparing to kill her. He said: “Saturday night I took the ‘rod’ and went out and stuck up a guy and took his care away from him. I drove the car home, I got the guns and stuff and drove to the house where the woman was staying. Ells had gone out with me a day or so before and pointed out to me and also told me just where she would be sleeping on the porch.”