Because it’s been a few days since we last visited the Stanley Beebe case I think that a brief synopsis is in order.

In December of 1942 Stanley Beebe was arrested for public intoxication. He was taken to LAPD’s Central Station where he later alleged he had been badly beaten. In a death bed statement to his wife, published in the L.A. Times, Beebe reiterated his claim. He died about ten days later of injuries that the coroner had determined were the result of a savage beating.

In December of 1942 Stanley Beebe was arrested for public intoxication. He was taken to LAPD’s Central Station where he later alleged he had been badly beaten. In a death bed statement to his wife, published in the L.A. Times, Beebe reiterated his claim. He died about ten days later of injuries that the coroner had determined were the result of a savage beating.

The Beebe case was a political hot potato–corruption and abuse by the cops terrified and enraged the citizens and just a few years earlier, in 1938, Angelenos had ousted Mayor Frank Shaw in a corruption scandal. Shaw was the first U.S. mayor to be recalled and the city was still reeling from the fallout of that national embarrassment.

The investigation into Beebe’s death was deftly stonewalled by a monumental lack of cooperation from LAPD. Finding the truth was going to be an uphill battle all the way, especially since people were being threatened if they didn’t drop the inquiry.

We’ll pick up the tale from there…

*******************************************

Deputy City Attorney Everett Leighton’s wife received a telephone call threatening her husband with death if he didn’t back-off the Stanley Beebe case. But it wasn’t just high profile city government types who were being threatened. Raymond Henry, 42, of 915 S. Mott Street was in jail when Stanley Beebe was allegedly beaten. If the D.A.’s investigators were looking for more info on Stanley’s case it wasn’t going to come from Raymond Henry. However, Henry did have a story to tell. He said that there had been another case of police brutality in the jail at approximately the same time.

There was an alley leading into the booking office and Raymond said he had seen a man dressed in khaki work clothes lying there and he appeared to have been beaten. Henry received a mysterious telephone call from a man claiming to be a cop; but unlike the call Everett Leighton’s wife had received Henry’s unknown caller made him an offer. The mystery man said he’d like to meet with Henry and offered to “pay all his expenses for a couple of days”. It was clear that someone wanted Raymond out of the way so he couldn’t testify about what he had seen.

There was an alley leading into the booking office and Raymond said he had seen a man dressed in khaki work clothes lying there and he appeared to have been beaten. Henry received a mysterious telephone call from a man claiming to be a cop; but unlike the call Everett Leighton’s wife had received Henry’s unknown caller made him an offer. The mystery man said he’d like to meet with Henry and offered to “pay all his expenses for a couple of days”. It was clear that someone wanted Raymond out of the way so he couldn’t testify about what he had seen.

In mid-February 1943 Chief Horrall ordered several LAPD officers jailed for their parts in the death of Stanley Beebe: Compton Dixon, James F. Martin, John M. Yates, E.P. Mooradian, McKinley W. Witt and Leo L. Johnson. The case became even uglier when it appeared that the police report had been falsified. A copy of the report showed Beebe’s occupation as machinist, he was an accountant; and his address was “transient” — yet the telephone call he’d been allowed to make had been to his wife at their apartment.

Every politician from Los Angeles to Sacramento sought to make political hay out of the issue of police brutality. Newspapers continued to report on new and increasingly alarming allegations of abuse of authority. One former prisoner said that he had been beaten while handcuffed and that large quantities of water and brandy had been forced down his throat.

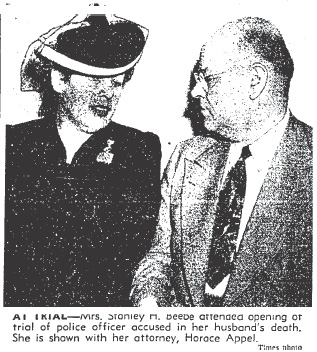

It was LAPD officer Compton Dixon who was finally accused of manslaughter in Beebe’s death. Compton didn’t fit Stanley’s description of his attacker, but there were several points on which Stanley had been understandably vague in his death bed statement to his wife. It was very possible he had incorrectly described his assailant.

Compton was indicted for Stanley’s murder on March 4, 1943, but he was immediately released on $10,000 bail when his Defense attorney Samuel Rummel and prosecutors stipulated that even if it was proved that Compton had beaten Beebe to death, it could possibly amount only to second-degree murder.

Because second degree murder carried a penalty of five years to life they decided he could be released on a bond.

Rummel’s reputation as a mouthpiece for crooked cops and local gangsters was well known, and deserved. Sam was friendly with gangster Mickey Cohen among other bad guys, but rubbing elbows with crooks isn’t a smart move. Rummel lived the high life hanging out with Cohen and various corrupt policemen, he was even part owner of a couple of Las Vegas casinos, but it all came to an end when he was shot gunned to death in the driveway of his Laurel Canyon home during the early morning hours of December 11, 1950. His slaying remains unsolved.

Two rookie officers had testified at the Grand Jury hearing that they’d witnessed Stanley’s beating. They were quite clear in their statements; but when it came time for them to testify in open court they were both suspiciously vague. In fact each of them said they had seen Stanley and they’d seen a foot on his stomach, but they just couldn’t be sure whose foot it was!

One by one, police officers who had previously admitted that they’d seen Compton Dixon beat Stanley Beebe retracted their statements. One of them, Leo Johnson, said that the statement he’d made at the LAPD training center on February 14th was made under duress:

One by one, police officers who had previously admitted that they’d seen Compton Dixon beat Stanley Beebe retracted their statements. One of them, Leo Johnson, said that the statement he’d made at the LAPD training center on February 14th was made under duress:

“That statement is false. It was not prepared by me and not written by me. Words were put in my mouth and the statements are untrue. I don’t ever remember seeing Dixon place his foot on anybody’s stomach.”

Officers with amnesia and revised statements should have been expected in Dixon’s trial, but there was one courtroom shocker that knocked the wind out of some of the observers.

Officers with amnesia and revised statements should have been expected in Dixon’s trial, but there was one courtroom shocker that knocked the wind out of some of the observers.

Deputy District Attorney Robert G. Wheeler, who handled the original investigation into the fatal beating, testified that after completing his inquiry he was of the opinion that Mrs. Maxine Beebe, widow of the dead man, could have murdered her husband!

When asked by Rummel on what facts he had based his conclusions, Wheeler responded:

“Only that Beebe was under her control from December 20 to December 27, and her evasiveness during the inquiry”.

I told you Sam Rummel was a mouthpiece for crooks.

Compton Dixon was questioned by Rummel about the alleged crime, quoted here verbatim from the L.A. Times:

“Did you strike Beebe?” Rummel asked.

“I did not,” Dixon replied with a firm voice.

“Did you kick him?”

“Never.”

“Did you jump on him?”

I did not.” Dixon said.

The case went to the jury and they deliberated for seven days before becoming deadlocked: 8 to 4 in favor of acquittal.

It was a disgusting miscarriage of justice. District Attorney Howser issued a statement in which he said the failure of the Los Angeles Police Department to solve the murder of the prisoner was due to:

“…concealed evidence and a misdirected investigation by members of the same department who were afraid disclosure of the truth would involve a member of members of the department.”

Dixon still had to face a police trial board–he had been suspended from duty since February. The LAPD board of rights concluded its investigation in July 1943 and they found Compton Dixon not guilty of conduct unbecoming an officer for refusing to testify before the grand jury. The board said that Dixon had been charged with manslaughter and the natural right of self-preservation, as well as his constitutional rights, superseded the general duty of an officer to testify before inquisitorial bodies.

Dixon was returned to duty and his back pay was restored. He retired in 1946 and because he had spent 20 years or more at a jail duty station he was presented with silver keys (that wouldn’t actually turn the locks) to the main doors of City Jail. It didn’t matter that the keys were phonies–Dixon didn’t need the real thing, he’d been given a “Get Out of Jail Free” card in 1943.

Dixon was returned to duty and his back pay was restored. He retired in 1946 and because he had spent 20 years or more at a jail duty station he was presented with silver keys (that wouldn’t actually turn the locks) to the main doors of City Jail. It didn’t matter that the keys were phonies–Dixon didn’t need the real thing, he’d been given a “Get Out of Jail Free” card in 1943.

None of the officers implicated in the various brutality cases being investigated at the time were punished, and no one was ever held accountable for Stanley Beebe’s death.

![LAPD Chief C.B. Horrall inspecting Detective Division c. 1947. [Photo courtesy UCLA Digital Collection.]](https://derangedlacrimes.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/horrall.jpg)