For more than forty years, Agness “Aggie” Underwood covered the crimes that terrified—and fascinated—Los Angeles. Murderers, mobsters, and corrupt officials all crossed her path. But the moment that set her career in motion wasn’t a gunshot or a headline. It was a pair of silk stockings she couldn’t afford.

In 1926, money was tight. Aggie and her husband, Harry, had a daughter, Evelyn, and a son, George. Her younger sister Leona lived with them and helped with expenses. Still, Aggie wore Leona’s hand-me-down silk stockings. One day, she asked Harry for money to buy a new pair. He said no. Aggie told him that if he wouldn’t give her money for stockings, she’d earn it herself.

She was bluffing. She hadn’t worked outside the home since 1920.

The next day, out of nowhere, her best friend Evelyn offered her a temporary switchboard job at the Daily Record. Aggie grabbed it. The stockings would be hers.

She described her first impression of the newsroom:

“I looked out on a weird wonderland… Shirt-sleeved men attacked beaten-up typewriters, which snarled and balked. Sheets of paper snowed on a central point called the city desk, whatever that meant. Men gyrated through the crazy quilt of splintered desks and tables. It was a jumble.”

The job was supposed to be temporary. But Gertrude Price, the women’s editor (writing as Cynthia Grey), saw something in Aggie and became her mentor. Aggie helped with the annual Cynthia Grey Christmas baskets, and Gertrude encouraged her to learn the business.

Aggie loved the chaos of the newsroom, and she loved being close to a breaking story. In December 1927, the city was horrified by the murder of twelve-year-old Marian Parker by William Edward Hickman, who called himself “The Fox.”

When news of Hickman’s capture in Oregon broke, Aggie couldn’t contain herself:

“As the bulletins pumped in and the city-side worked furiously at localizing, I couldn’t keep myself in my niche. I committed the unpardonable sin of looking over shoulders of reporters as they wrote. I got underfoot. In what I thought was exasperation, Rod Brink, the city editor, said:

‘All right, if you’re so interested, take this dictation.’

I typed the dictation—part of the main running story.

I was sunk.

I wanted to be a reporter.”

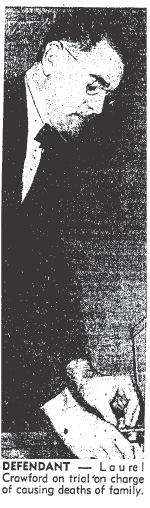

She began writing human interest stories, covering fashion and women’s clubs. In May 1931, her first major break came when Charles H. Crawford (a.k.a. the Grey Fox) and reporter Herbert F. Spencer were shot and killed.

Crawford was a former saloon keeper turned vice king. Spencer had worked with a political crusading weekly, the Critic of Critics. They were both involved in the shadowy network known as “The Combination”—a marriage of City Hall and organized crime.

After the murders, David H. Clark, a former deputy DA and candidate for judge, surrendered. But no one had interviewed Clark’s parents. Aggie called every Clark in the phonebook until she found them in Highland Park.

She got the interview. The result: a front-page, above-the-fold story titled Mrs. Clark Says Son is Innocent. Her first double-column byline.

Later, she scored another exclusive with Spencer’s widow. Aggie admitted she was inexperienced—and that honesty earned her the story.

Clark was acquitted. But he drifted. In 1953, he killed a friend’s wife in a drunken fight and died in Chino prison in 1954.

Aggie had found her niche—finding the doors no one else knocked on.

In 1935, she joined the Evening Herald and Express, owned by William Randolph Hearst. She stayed with Hearst the rest of her career.

By 1936, Aggie had a reputation as a reporter who could crack a case. During the Samuel Whittaker case, she interviewed the grieving husband, a retired organist, after his wife Ethel was killed during an apparent hotel robbery.

She staged a dramatic photo of Whittaker pointing his cane at the alleged killer, James Fagan Culver. But as she posed the shot, she noticed something odd: Whittaker winked at Culver.

Was it a tic? No. She waited. Nothing. She discreetly pulled Detective Thad Brown aside:

“Thad, ask that kid why Whittaker winked at him. Don’t let the kid wriggle out of it. Whittaker did wink at him. There’s no mistake about it.”

Brown humored her. Culver cracked. He confessed: Whittaker had staged the robbery, armed Culver with a .38, and planned to kill his wife himself. He did—then turned his gun on Culver. Culver escaped, wounded.

Whittaker was convicted and given life for his wife’s murder. On his way to San Quentin, he said:

“I hope God may strike me dead before I get to my cell if I am guilty of this horrible crime.”

He dropped dead of a heart attack.

In January 1947, Aggie began reporting on the body of an unknown woman found bisected in Leimert Park. She would become known as the Black Dahlia.

Many claim to have coined the name. Aggie said she got it from LAPD Lt. Ray Giese:

“This is something you might like, Agness. I’ve found out they called her the ‘Black Dahlia’ around that drugstore where she hung out down in Long Beach.”

Like it? She LOVED it.

The Jane Doe was soon identified as 22-year-old Elizabeth Short of Medford, MA. Aggie interviewed the first serious suspect, Robert “Red” Manley. Then she was pulled from the case.

She brought in her embroidery hoop while she cooled her heels in the office. Snickers followed. One reporter said:

“What do you think of that? Here’s the best reporter on the Herald, on the biggest day of one of the best stories in years—sitting in the office doing fancy work!”

She was reassigned, then yanked again. And then—she was promoted to city editor.

Dahlia conspiracy theorists say Aggie was close to solving the case. Some believe she was silenced. But promoting her to city editor—the boss of all the Dahlia reporters—was a strange way to shut her up.

Still… what if she was onto something?

When asked later if she knew who killed Elizabeth Short, she said yes—but never named him.

Mercy? Resignation? Maybe both.

Aggie understood something this city still struggles with: some crimes don’t end in arrests. They end in silence.

She covered L.A.’s most deranged crimes. As city editor, she won dozens of awards and the respect of her newsroom. On her 10th anniversary, her crew gave her a giant novelty baseball bat—like the one she kept on her desk to scare off pesky Hollywood types. It read:

“To Aggie, Keep Swinging.”

Reporter Will Fowler said in his autobiography:

“The last thing I remember Aggie saying to her friends who came to celebrate at her retirement party was: ‘Please don’t forget me.’”

She had a bat on her desk and a city full of secrets.

We couldn’t forget her if we tried.

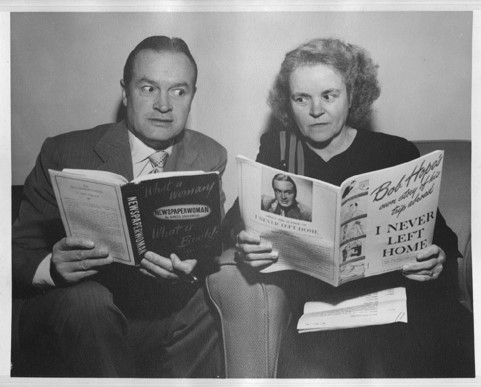

NOTE: If you want to know more about Aggie’s crime reporting, get a copy of the my book, THE FIRST WITH THE LATEST!: AGGIE UNDERWOOD, THE LOS ANGELES HERALD, AND THE SORDID CRIMES OF A CITY.

![1933 Long Beach earthquake [Photo courtesy LAPL]](https://derangedlacrimes.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/07/00058883_1933-quake-300x231.jpg)

![Elizabeth Short aka The Black Dahlia [Photo courtesy LAPL]](https://derangedlacrimes.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/07/00010499_beth-short.jpg)

![Robert "Red" Manley [Photo courtesy LAPL]](https://derangedlacrimes.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/07/00063980_manley_lie.jpg)