Agness “Aggie” Underwood passed away 29 years ago today. We never met but she has had a profound influence on my life, particularly during the last several years.

I’ve been obsessed with crime novels and true crime since I was a kid, and my compulsion to read it has never diminished. Writing about true crime is a relatively new endeavor for me and I attribute that, in large part, to Aggie’s influence. She is the inspiration for this blog and for the Deranged L.A. Crimes Facebook page, and I am proud to have authored her Wikipedia page — she was long over due for recognition.

As I’ve dug deeper into the crimes that have shocked and, in some ways, defined Los Angeles, I’ve felt Aggie’s presence. Aggie worked in Los Angeles from the late 1920s through the late 1960s — and for nearly two decades she was a reporter. My interest in history and crime set me on the path to write about it, but it’s been my admiration for Aggie that has made me want to tackle many of the same cases that she wrote about.

I gave a lecture at the Central Library in downtown Los Angeles on June 29th entitled SLEEPING BEAUTIES: DERANGED L.A. CRIMES FROM THE NOTEBOOK OF AGGIE UNDERWOOD — here is an excerpt from my presentation. I hope you enjoy it.

Thanks for everything, Aggie.

***************************************************

In 1926 as a young wife and mother Aggie had no interest in working outside the home, but she wanted a pair of silk stockings in the worst way. When her husband, Harry, told her that there wasn’t enough money in the budget for her to buy them, Aggie said she’d get a job and earn the money.

Aggie quickly realized that she may have put her foot in her mouth rather than into a new pair of silk stockings; she didn’t have a clue about where to find work. Fate intervened when a friend of hers, who worked at the THE RECORD, phoned and told her that the newspaper needed someone to temporarily operate the switchboard. Aggie took the job and it would turn out to be one of the most important decisions of her life.

Aggie came to enjoy the hustle and bustle of the newsroom and she loved being in the midst of a breaking story. In December 1927, the city was horrified when William Edward Hickman, who called himself “The Fox” murdered and then butchered twelve year old school girl, Marian Parker. Hickman fled after the murder and the resulting manhunt was one of the biggest in the West.

In her autobiography Aggie recalled how she felt when they got the word that Hickman had been captured in Oregon:

“As the bulletins pumped in and the city-side worked furiously at localizing, I couldn’t keep myself in my niche. I committed the unpardonable sin of looking over shoulders of reporters as they wrote. I got under foot. In what I thought was exasperation, Rod Brink, the city editor, said:

‘All right, if you’re so interested, take this dictation.’

I typed the dictation—part of the main running story. I was sunk. I wanted to be a reporter.”

She eventually got her wish and began reporting on stories for THE RECORD. Smart and hardworking, she made a name for herself locally and was courted by William Randolph Hearst for his publishing empire.

She resisted his overtures (and even his offers of more money) because she was happy at THE RECORD. The smaller paper gave her the opportunity to learn all aspects of the business – she thought working for Hearst might pigeon-hole her.

It wasn’t until THE RECORD folded in 1935 that Aggie agreed to become a reporter for THE HERALD. She said that she had heard the term “working for Hearst” uttered contemptuously; but she had been too busy learning her craft to pay much attention to the gibes.

She said:

“…I did not feel I stigmatized myself when I accepted the HERALD-EXPRESS offer. The invitation was a life line, and one did not need to be bereft of ideals to tie onto it.”

In her 1949 autobiography, NEWSPAPERWOMAN, Aggie described what it was like to be a reporter on the Herald:

“The Herald-Express is too fast for the sort of reporter who flounders when he is required to produce a new lead on a running story for each upcoming edition “

Aggie never floundered. She had reported from the scenes of disasters like the 1933 Long Beach earthquake, and she’d also covered some of the most heinous crimes committed in the city.

During the 1930s there were several daily papers in Los Angeles and Aggie had to be a fierce competitor. In her autobiography Aggie wrote about the time she beat another reporter to some photos:

“Once, on a rather cheap murder and suicide, Casey Shawhan, then an Examiner reporter, and I were rifling a bureau drawer for pictures—no we weren’t housebreaking—when we grasped a pile of photographs simultaneously. The tug of war was unequal, for Casey had played football at U.S.C. So I kicked him in the shin. He let go of the pictures and, clasping his bruise, danced on his other leg, howling, ‘O-o-h, gahdammit. I’ll get even with you, Underwood. You wait and see.’” I didn’t wait. I was scurrying off to the office with the pictures.”

Aggie thought of herself as a general assignment reporter; however, she gained a reputation as a crime reporter. Good detectives are observers and so are good reporters, which may explain why stories circulated that Aggie had solved crimes.

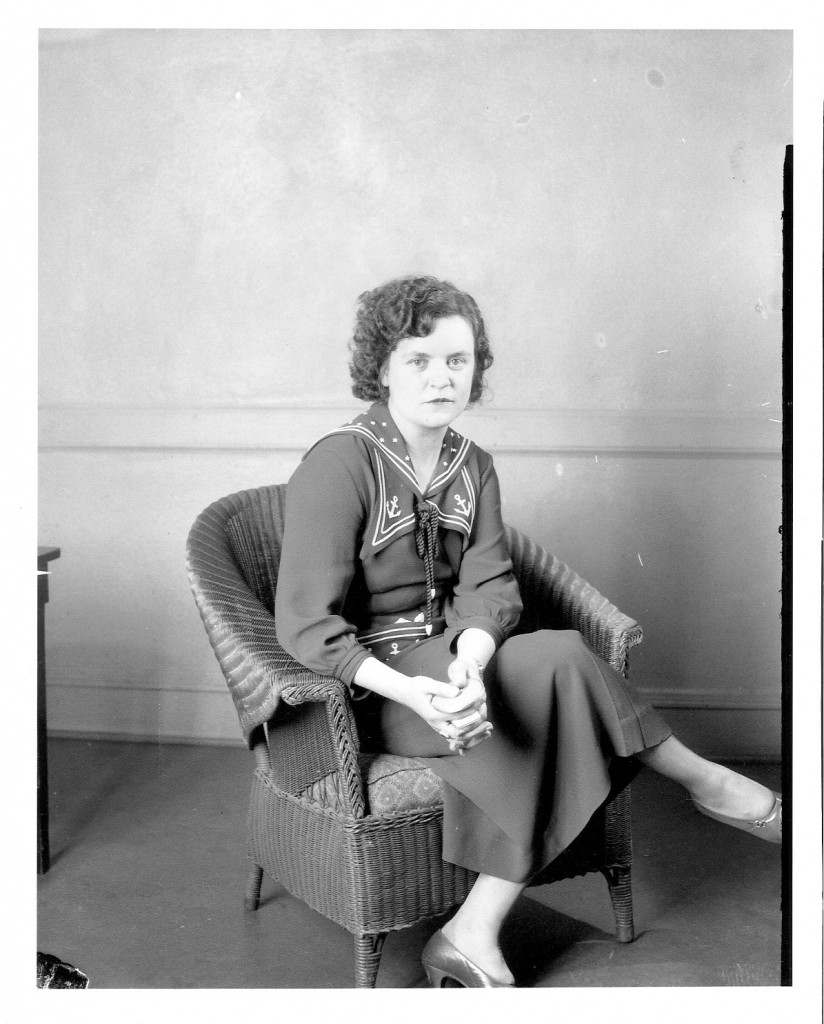

Aggie interviewing an unknown bad dame at Lincoln Heights Jail. [Photo courtesy of CSUN Special Collections]

In late 1939, Aggie went out on a story that appeared to be a tragic accident – a family of five had been killed when their car had tumbled hundreds of feet down a mountainside near the Mt. Wilson Observatory. There was one survivor, the husband and father of the victims, Laurel Crawford.

Aggie wasn’t allowed to interview him because cops felt he’d been through enough; however, Aggie made a deal with one of the deputies who allowed her to listen in while Crawford was being questioned. Aggie observed the man, and she had a hunch. One of the Sheriff’s department homicide investigators asked Aggie:

Aggie wasn’t allowed to interview him because cops felt he’d been through enough; however, Aggie made a deal with one of the deputies who allowed her to listen in while Crawford was being questioned. Aggie observed the man, and she had a hunch. One of the Sheriff’s department homicide investigators asked Aggie:

“What do you think of it, Aggie?”

She didn’t hesitate, and replied:

“I think it smells. He’s guilty as hell.”

Aggie had observed not only Crawford’s demeanor, which led her to believe his display of grief was disingenuous, but she had also noticed that his shoes weren’t scuffed, and his clothing wasn’t dirty, torn or wrinkled, which made his story of climbing down the mountain to the wreckage of the family sedan pretty tough to believe. Additionally, Crawford had stated that he had picked up the body of one of his daughters and held her, but there was no evidence of blood on his clothing. Aggie’s Spidey-Sense was engaged.

A thorough investigation of the case proved that Crawford had taken out insurance policies on each of the victims, worth a total of $30,500 (that’s over half a million in today’s money!) Laurel Crawford was sentenced to four consecutive life terms with a recommendation that he never be paroled.

For years Aggie covered everything from celebrity trials to gruesome murders. In January 1947 arguably the most infamous murder case in L.A.’s history broke; the mutilation slaying of twenty-two year old Elizabeth Short.

Underwood was assigned to the story. There have been several people over the years who have claimed credit for naming the victim The Black Dahlia; and Aggie was one of them. Aggie said that the Black Dahlia tag was dug out on a day when everyone was combing blind alleys. She decided to check in with Ray Giese, a Det. Lt. in LAPD homicide, to see if any stray fact may have been overlooked.

According to Aggie, he said: “This is something you might like, Agness. I’ve found out they called her the ‘Black Dahlia’ around that drug store where she hung out down in Long Beach”. Like it? She LOVED it!

Aggie interviewed Robert “Red” Manley, the first serious suspect in the Black Dahlia case, and she was prepared to follow the story to its conclusion when without warning, she was benched.

After a couple of days of cooling her heels in the newsroom she decided to bring in her embroidery hoop. Pretty soon she heard snickers. Aggie said that one of her colleagues laughed out loud and said:

“What do you think of that? Here’s the best reporter on the Herald, on the biggest day of one of the best stories in years—sitting in the office doing fancy work!”

Aggie was quickly reassigned to the Dahlia case, and just as quickly yanked off of it. It was then that she was given the news that she was being promoted to city editor! Aggie said she never understood the timing of her promotion – she would have preferred to follow the Dahlia story until it went cold. But it was an important moment in her career and for women in journalism – Aggie was the first woman in the U.S. to become the City Editor of a major metropolitan newspaper!

*********************************************************************

P.S. I’m currently researching the Laurel Crawford case — it’s diabolical.

![Aggie & Harry [Photo courtesy CSUN Special Collections]](https://derangedlacrimes.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/07/aggie_harry.jpg)

![1933 Long Beach earthquake [Photo courtesy LAPL]](https://derangedlacrimes.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/07/00058883_1933-quake-300x231.jpg)

![Elizabeth Short aka The Black Dahlia [Photo courtesy LAPL]](https://derangedlacrimes.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/07/00010499_beth-short.jpg)

![Robert "Red" Manley [Photo courtesy LAPL]](https://derangedlacrimes.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/07/00063980_manley_lie.jpg)