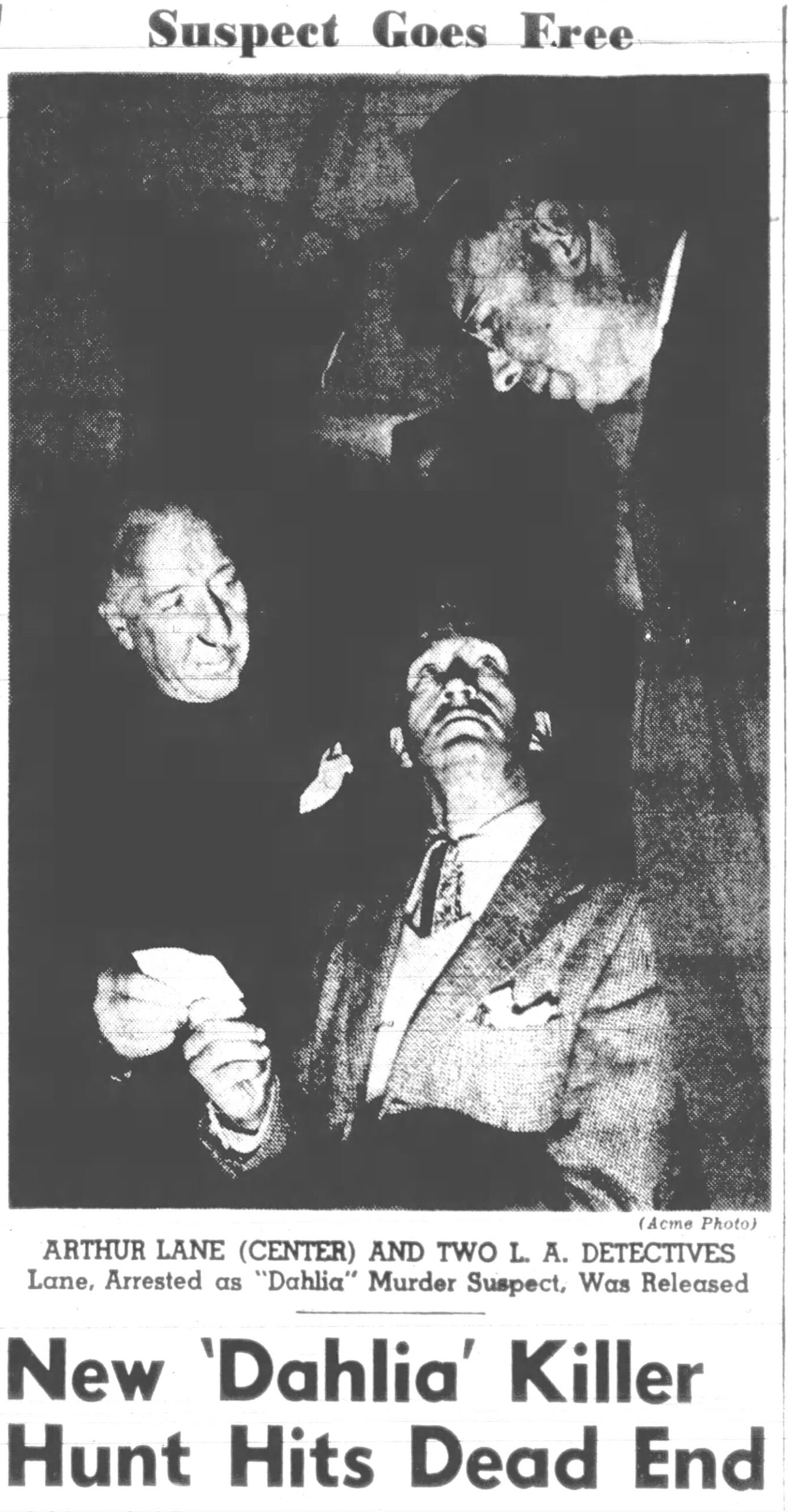

Two years passed with police no closer to a solution for Elizabeth Short’s murder. The 1949 Los Angeles Grand Jury intended to hold LAPD’s feet to the fire for failing to solve the Dahlia case and several other unsolved homicides and disappearances of women during the 1940s.

On September 6, 1949, the jury’s foreman, Harry Lawson, told reporters that the administrative committee scheduled a meeting for September 8.

Lawson said:

“There is every possibility that we will summon before the jury officers involved in the investigation of these murders. We find it odd that there are on the books of the Los Angeles Police Deportment many unsolved crimes of this type. Because of the nature of these murder and sex crimes, women and children are constantly placed in jeopardy and are not safe from attack. Something is radically wrong with the present system for apprehending the guilty. The alarming increase in the number of unsolved murders and other major crimes reflects ineffectiveness in law enforcement agencies and the courts, and that should not be tolerated.”

In his statement, Lawson places the blame for the unsolved homicides squarely on the shoulders of law enforcement and the courts. What Lawson failed to understand was that crime was changing. No longer could police assume a woman’s killer was her husband or boyfriend. Stranger homicides were nothing new, but neither were they common.

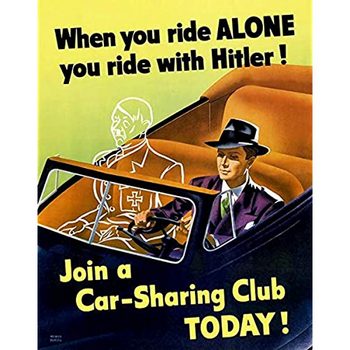

The population of post-war Los Angeles skewed young and, because of a variety of factors, like the acute housing shortage, they were transient. A potent and deadly mix of opportunity and a large victim pool made it easy for the criminally inclined to do their worst. Women had a false sense of security about men in uniform. Behavior considered risky by today’s standards was acceptable during the 1940s.

From the outbreak of the war, the government encouraged women to support men in uniform. Newspapers and women’s magazines devoted countless column inches to ways in which they could aid fighting men. Women formed “Add-A-Plate” clubs. The mission of the clubs was to invite a soldier home for a meal. Women also routinely picked up soldiers and sailors hitchhiking because it was their patriotic duty.

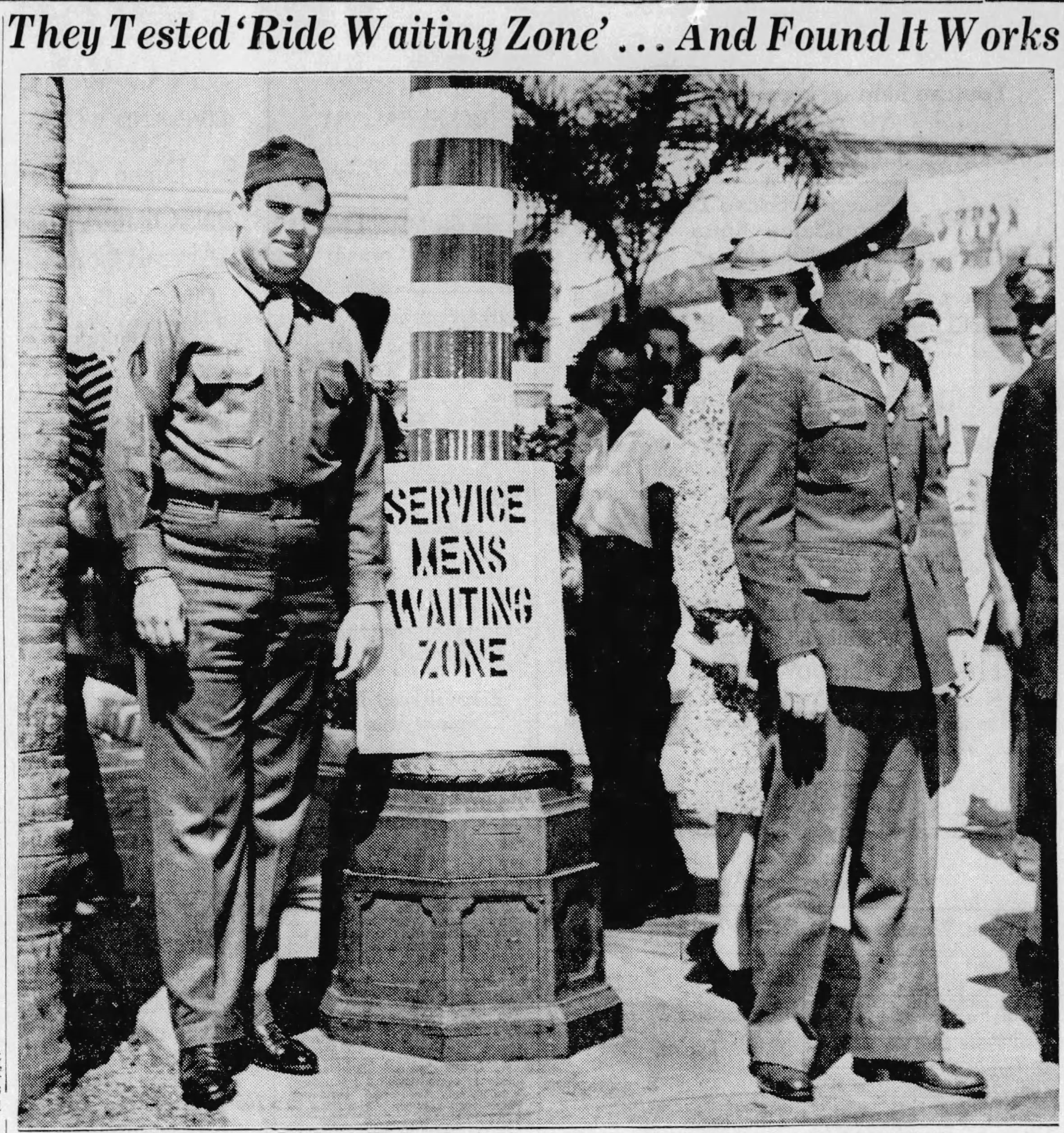

On April 2, 1943, the Pasadena Post wrote about a “ride waiting zone” which gave military men a place to stand and be visible to passing motorists who would then give them a ride. Most of the men were decent and law-abiding, but some returned home severely damaged by their war experiences. How many of those men were capable of murder?

LAPD detectives spared nothing in their investigation of Short’s slaying. They took over 2700 reports. There were over 300 named suspects. They arrested fifty suspects who they subsequently cleared and released. Nineteen false confessors wasted law enforcement’s time and resources.

In 1949, the DA’s office issued a report on the investigation into Short’s murder. In part, the report stated:

“[she] knew at least fifty men at the time of her death and at least 25 men had been seen with her within the 60-day period preceding her death. She was not a prostitute. She has been confused with a Los Angeles prostitute by the same name… She was known as a teaser of men. She would ride with them, chisel a place to sleep, clothes or money, but she would then refuse to have sexual intercourse by telling them she was a virgin, or that she was engaged or married. There were three known men who had sexual intercourse with her and, according to them, she got no pleasure out of this act. According to the autopsy surgeon, her sex organs showed female trouble. She had disliked queer women very much, as well as prostitutes. She was never known to be a narcotic addict.”

Distracted by the continuing saga of local gangster Mickey Cohen, the jury turned their attention away from the carnage. In the end, they passed the baton to the 1950 grand jury–which also found itself sidetracked.

What happened to the women who disappeared? It is unlikely that we will ever know. It is also unlikely we will identify the killer(s). People will always speculate about the cases, and every few years a book about the Black Dahlia slaying will emerge claiming to have solved the decades long cold case. None of the books I’ve read so far is credible.

I do not accept theories which rely on elaborate conspiracies perpetrated by everyone, from a newspaper mogul to a local gangster to an allegedly evil genius doctor. My disbelief is based in part on the fact that most people are incapable of keeping a secret. Benjamin Franklin said, “Three (people) can keep a secret if two of them are dead.” Eventually, someone talks.

Elizabeth Short’s killer probably kept his depraved secret but, even if he didn’t, anyone who knew the truth is long dead.

NOTE: This concludes my series of Black Dahlia posts for now. I hope you will stay with me through 2023 as I unearth more of L.A.’s most deranged crimes.