The investigation into Beth Short’s murder grew colder every day. Police investigated all the crackpots who claimed responsibility for the heinous crime. They went through stacks of letters and postcards that named potential suspects and offered various theories about the culprit. They rousted local sex offenders and searched in vain for the crime scene. If only the killer would confess.

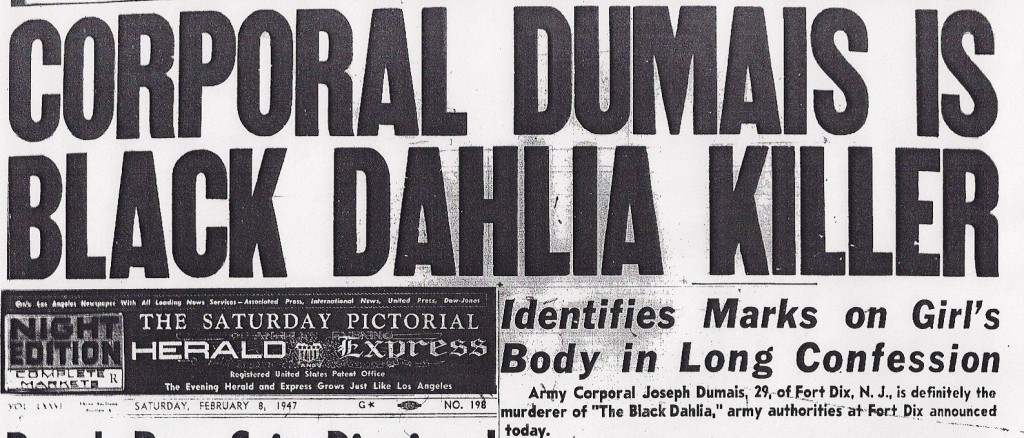

On February 8, 1947, Joseph Dumais, an Army Corporal, came forward and admitted he dated Beth Short. Not only had they dated, he was sure he had killed her. The Herald announced “Corporal Dumais Is Black Dahlia Killer.” The story began, “Army Corporal Joseph Dumais, 29, of Fort Dix, N.J., is definitely the murderer of ‘The Black Dahlia,’ army authorities at Fort Dix announced today.”

Dumais returned to Fort Dix wearing blood-stained trousers with his pockets crammed full of clippings about the murder. In a hand-written 50-page confession, he claimed he dated Beth five days before the discovery of her body—then he suffered a mental blackout.

The good-looking corporal seemed like the real deal. Army Capt. William R. Florence, head of the Fort Dix Criminal Investigation Department, said, “I am definitely convinced that this man is the murderer.” In his zeal to be the one to solve the gruesome murder, Capt. Florence overlooked the superficial nature of Dumais’ answers to his questions. Dumais had only to read the news coverage of the case, and then unleash his imagination to be credible in the short run. When Florence asked, “Does it seem to you at this time that you committed this crime? Dumais answered yes. But as Dumais stated earlier, he blacked out and recalled nothing until he arrived at Penn Station.

Getting to the nitty-gritty details, the Capt. asked, “Do you know how her body was mutilated?” Dumais said he did, but did not wish to describe the injuries. Again, Capt. Florence asked Dumais if he could have committed the murder. Dumais replied, “Yes, it is possible because of my actions in the past.”

In his confession, Dumais told Army authorities he stabbed Beth in the back and around the mouth, then severed her body with a meat cleaver. He washed the body of blood and dumped it in a vacant lot in Leimert Park.

Dumais’s story was riddled with holes. He said he had a date with Beth in San Francisco on January 9 or 10, but could not explain how he got to Los Angeles and then back to Fort Dix. Further questions revealed Dumais to be a blackout drunk. He said he was “rough on the girls” when he had been drinking. Dumais’s credibility eroded with each new statement.

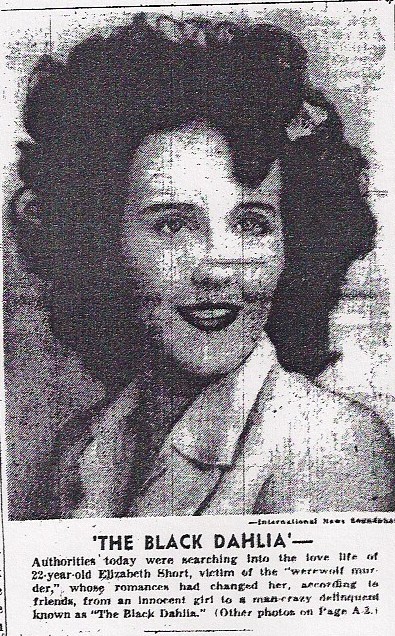

On February 10th, as Dumais’s story unraveled, Los Angeles awakened to the news of another brutal murder of a woman. The Herald put out an extra edition with the headline, “Werewolf Strikes Again! Kills L.A. Woman, Writes B.D. on Body”.

The victim of the “Werewolf Killer” was forty-five-year-old Jeanne French. Her nude body was discovered at 8 a.m. on February 10, 1947, near Grand View Avenue and Indianapolis Street in West L.A. Police were frustrated and overworked. The women of Los Angeles were terrified. What the hell was going on?

NEXT TIME: The Lipstick Murder