About 2:30 a.m., on February 1, 1931, after a night of nightclubbing, twenty-four-year-old Julia Tapia and several of her girlfriends stopped at Alfonso’s Café at Temple and Figueroa for a bite to eat. Julia wanted to sober up before leaving on a quick turn-around trip north.

A friend of hers, Harvey Hicks, missed his train to Tehachapi, about one hundred miles north of Los Angeles. She had nothing better to do, so she said she would drive him there. She had no desire to make the return trip by herself. She would have asked her girlfriends to accompany her, but they were “family girls,” not the type to take a trip on the spur-of-the-moment.

Julia didn’t scoff at family girls, but she knew she wasn’t one herself. She was married, but her husband left for Mexico five months earlier, and had not returned. She was recently “vagged,” which is a vagrancy charge, usually prostitution. She spent ten days in the county jail rather than pay a $50 fine.

She scanned the café for another girl, not the family type, who might take the Tehachapi jaunt with her. She spotted Adeline Ortega. Julia and Adeline weren’t close, but they’d seen each other around, and had chatted before at Alfonso’s. Adeline had recently been “vagged,” too. Julia persuaded her to come along for the ride. They would have lots to talk about on the way home.

Adeline made only one request. She wanted her friend Manuel to join them. Julia didn’t object; what the hell, the more the merrier. Four young people in a car, a pint and a half of illegal booze, and a few hours on a dark highway–it would be a miracle if trouble didn’t find them. Miracles never happened to Julia.

The trip to Tehachapi was uneventful. They took Harvey to the home of a friend of his, and spent about thirty minutes passing a bottle of whiskey around. When it came time to leave, Manuel said he was exhausted. He stretched out on the back seat of Julia’s car and nodded off. Julia drove while Adeline kept her company. A little later, Adeline got sleepy and switched places with Manuel.

Manuel was the perfect passenger until he started pestering Julia to let him drive. She refused. The two had words, and Manuel tried to throw the car out of gear and grab the steering wheel. Julia, accustomed to dealing with men who would not take no for an answer, told Manuel to cut the crap or she would put him out on the highway. Manuel got belligerent and declared he’d leave the car willingly.

After Manuel got out, Julia drove her car, a 1930 Chevrolet, in low gear down the road. She was a softer touch than she seemed. She would give Manuel another chance to behave. But minutes after he got out of her car, she saw a light-colored car, with three guys in it, pick him up. The car caught up with Julia; Adeline still slept in the backseat. When the car pulled up alongside her, Manuel shouted he left his overcoat and hat behind and wanted to retrieve them. Julia reached over to the passenger’s side and grabbed his belongings. She threw them out of the car at him.

Manuel got angry. He jumped onto the running board of her car. He was on the driver’s side, screaming abuse at her. Then, he reached over and pulled her hair and smacked her hard on the jaw. She noticed Harvey had left his .38 revolver stuck in the seat cushion. She grabbed the gun and shot Manuel right above his heart. He fell from the running board and tumbled to the pavement.

Julia braked the car to a stop and ran over to him. He was lying in a pool of blood, wheezing. He was about two heartbeats away from death. She dragged him to the side of the road. The car that Manuel had hitched a ride on sped off into the night. Seconds later, another car with three men in it pulled up to see what was going on. In the car were Dean Markham and his buddies, Joe Frigon, and Bob Tittle. The trio were rabbit hunting in Mojave, and headed back to L.A.

Markham got out of the car, and walked over to speak with Julia. On his way over to talk to the distraught woman, he noticed a pool of dark-colored liquid, and Manuel on the pavement. He stepped wide.

Markham’s car had overheated. They left Julia and Adeline behind, and took Julia’s car to fetch help in nearby Lancaster. They arrived at a hotel and asked the clerk where to find a cop. The clerk pointed at a pool hall down the street. He suggested they would find an officer there. Sure enough, just as the clerk said, Markham and his buddies found an officer shooting pool.

Markham, et al., piled into Julia’s car, and returned to the scene. They could hear the siren wailing on the police car ahead of them as they sped down the highway.

Markham, his friends, and the officer, pulled up to the scene. Julia and Adeline stood in the road, shell-shocked. No wonder. The local undertaker beat the cop to the scene. He loaded Manuel’s body into his hearse and drove it away.

In the days following Manuel’s death, his business partner asked about $500 (equivalent to $10,500.00 in 2023 U.S. dollars) Manuel carried with him. He was supposed to have deposited it. The morgue property slip listed the dead man’s belongings. No mention of money.

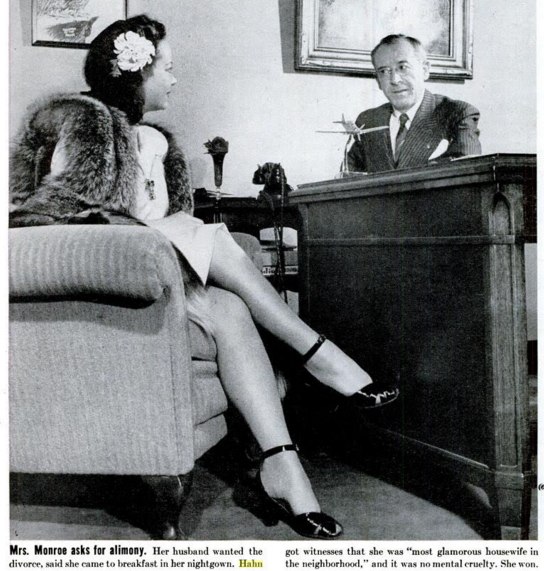

They indicted Julia for Manuel’s murder on April 27, 1931. The case was called for trial in Department 27 of Superior Court; Judge Walton J. Wood presiding, Deputy District Attorney Barnes representing the People, and S .S. Hahn representing the defendant. The Deputy D.A. who prepared the case against Julia, was unavailable. Barnes requested a continuance. Judge Wood denied the motion and ordered Barnes to proceed with the trial.

At the conclusion of the state’s case, prior to being submitted to the jury, S. S. Hahn moved for an instructed verdict. The judge agreed with Hahn that all the evidence showed Julia shot Manuel in self-defense.

Julia left the court a free woman. Was she $500 richer? We’ll never know.

NOTE: This is an encore post from December 2012. This is one of the first posts I wrote for the blog. As I did then, I want to thank my crime buddy, Mike Fratantoni, curator of the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department Museum. He told me this story because he knows I have a weakness for tales about bad girls, and cars with running boards.

According to Hahn, the woman (whom Hahn described as an attractive 28-year-old brunette) said she and Earle had been lovers for more than eighteen months, but his interest in her began to wane. She tried unsuccessfully to hold on to him. The woman told Hahn: “I loved Remington and expected him to marry me. I first began to share his love more than a year and a half ago. I had been married. I knew he was married, but he promised that he would obtain a divorce and marry me. For a year we were happy. He and I lived together for a time at the beach at Venice. Then gradually his love seemed to cool. He missed his appointments with me and I say less and Less of him.”

According to Hahn, the woman (whom Hahn described as an attractive 28-year-old brunette) said she and Earle had been lovers for more than eighteen months, but his interest in her began to wane. She tried unsuccessfully to hold on to him. The woman told Hahn: “I loved Remington and expected him to marry me. I first began to share his love more than a year and a half ago. I had been married. I knew he was married, but he promised that he would obtain a divorce and marry me. For a year we were happy. He and I lived together for a time at the beach at Venice. Then gradually his love seemed to cool. He missed his appointments with me and I say less and Less of him.” Two months turned into two years, then twenty. It has now been nearly 95 years since Earle was murdered in the driveway of his home. Yet, there was a brief glimmer of hope when a WWI veteran, Lawrence Aber, confessed. His reason? He said he was angry at Earle for selling liquor to veterans. It didn’t take long for the police to realize that Aber had lied. He wasn’t being malicious, he suffered from severe mental issues and he was in a hospital at the time of the slaying.

Two months turned into two years, then twenty. It has now been nearly 95 years since Earle was murdered in the driveway of his home. Yet, there was a brief glimmer of hope when a WWI veteran, Lawrence Aber, confessed. His reason? He said he was angry at Earle for selling liquor to veterans. It didn’t take long for the police to realize that Aber had lied. He wasn’t being malicious, he suffered from severe mental issues and he was in a hospital at the time of the slaying. Gray was scheduled to take the stand on November 2nd but he was too ill to appear in court. The trial was delayed for a few days until it was decided that if Gray couldn’t come to court, the court would come to him. The trial resumed at Gray’s bedside in the County Jail Hospital.

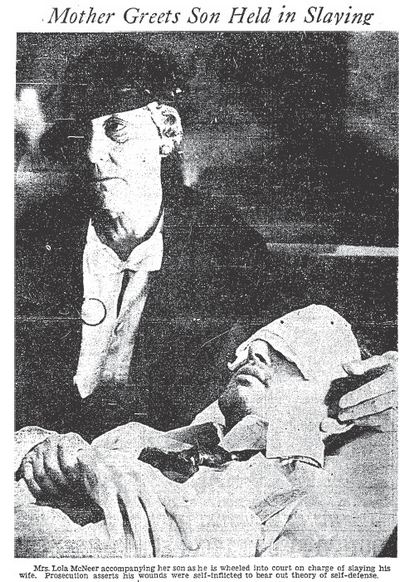

Gray was scheduled to take the stand on November 2nd but he was too ill to appear in court. The trial was delayed for a few days until it was decided that if Gray couldn’t come to court, the court would come to him. The trial resumed at Gray’s bedside in the County Jail Hospital.

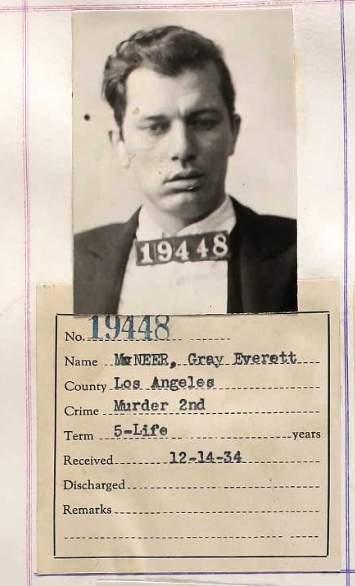

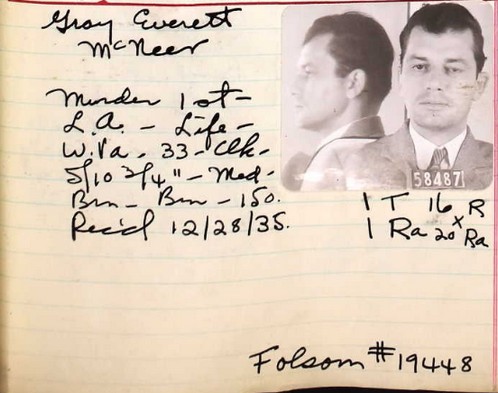

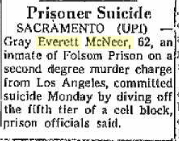

Gray was taken to Folsom Prison to begin serving his sentence of from 5 years to life. Gray’s mother said there was no plan to file an appeal. But plans change.

Gray was taken to Folsom Prison to begin serving his sentence of from 5 years to life. Gray’s mother said there was no plan to file an appeal. But plans change.

Gray’s mother, Lola, remained at her son’s bed side and on August 24th it was reported that she had given her official consent for an operation to remove the bullet from his brain. It isn’t clear why a man in his 30s would need his mother’s consent, but it may have been that he was in no condition to give it himself. S.S. Hahn told the court that in his present condition Gray was in imminent danger of death and that, even if he survived, he might be become “an imbecile.” The operation was given odds of 100 to 1 that it would succeed; but it was Gray’s only hope.

Gray’s mother, Lola, remained at her son’s bed side and on August 24th it was reported that she had given her official consent for an operation to remove the bullet from his brain. It isn’t clear why a man in his 30s would need his mother’s consent, but it may have been that he was in no condition to give it himself. S.S. Hahn told the court that in his present condition Gray was in imminent danger of death and that, even if he survived, he might be become “an imbecile.” The operation was given odds of 100 to 1 that it would succeed; but it was Gray’s only hope. Hahn objected to the Judge’s admonition and there was a short recess. Once back in the courtroom, Judge Burnell spoke to the jury: “Ladies and gentlemen of the jury, I am making this statement to you at the suggestion and with the consent of counsel for both sides, the People and the defendant. You, of course, could not help but observe the fact yesterday afternoon that the defendant was making more or loess noise, talking and groaning, and the Court made some remarks about ceasing the theatricals, or something of that sort. That, of course, is something that you haven’t any business to pay any attention to, and I want you to entirely disregard it. The defendant is here on trial for one specific offense, and all the jury have any right to consider whatever is the evidence in the case and nothing else. I know you will appreciate that and be able to do that, but for your information, in view of the apparent condition of the defendant, I am trying now to get hold of Dr. Blank, the jail physician, to come down here and tell us whether he thinks from his examination of the defendant there is any reason why the case should not continue. In other words, whether or not the defendant is in a condition physically and mentally that will preclude going ahead with the trial. Until we hear from Dr. Blank, we will go ahead, and if there is any demonstration on the part of the defendant, you will disregard it. You are not here to try anything except the facts in this case.”

Hahn objected to the Judge’s admonition and there was a short recess. Once back in the courtroom, Judge Burnell spoke to the jury: “Ladies and gentlemen of the jury, I am making this statement to you at the suggestion and with the consent of counsel for both sides, the People and the defendant. You, of course, could not help but observe the fact yesterday afternoon that the defendant was making more or loess noise, talking and groaning, and the Court made some remarks about ceasing the theatricals, or something of that sort. That, of course, is something that you haven’t any business to pay any attention to, and I want you to entirely disregard it. The defendant is here on trial for one specific offense, and all the jury have any right to consider whatever is the evidence in the case and nothing else. I know you will appreciate that and be able to do that, but for your information, in view of the apparent condition of the defendant, I am trying now to get hold of Dr. Blank, the jail physician, to come down here and tell us whether he thinks from his examination of the defendant there is any reason why the case should not continue. In other words, whether or not the defendant is in a condition physically and mentally that will preclude going ahead with the trial. Until we hear from Dr. Blank, we will go ahead, and if there is any demonstration on the part of the defendant, you will disregard it. You are not here to try anything except the facts in this case.”![S.S. Hahn with a witness in Aimee Semple McPherson's trial. [Photo courtesy of LAPL]](https://derangedlacrimes.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/00021982_hahn_witness-in-McPherson-trial.jpg)

Police identified the victims as Gray (Grey) Everett McNeer and his estranged wife, Beatrice (Betty) Helene Harker McNeer. While fighting for his life in the General Hospital Gray managed a brief statement in which he laid the blame for the shootings on his dead wife. Unfortunately for Gray the physical evidence suggested a far different scenario.

Police identified the victims as Gray (Grey) Everett McNeer and his estranged wife, Beatrice (Betty) Helene Harker McNeer. While fighting for his life in the General Hospital Gray managed a brief statement in which he laid the blame for the shootings on his dead wife. Unfortunately for Gray the physical evidence suggested a far different scenario. With Gray in the hospital, Detective Lieutenants Sanderson and Hill of the police department began their investigation into the backgrounds of the McNeers.

With Gray in the hospital, Detective Lieutenants Sanderson and Hill of the police department began their investigation into the backgrounds of the McNeers.