Grace Munro filed a $50,000 lost-love (alienation of affection) suit against her husband’s young paramour, Clara Eunice Barker. But Clara had a trump card to play; a bundle of love notes written to her by none other than Grace’s husband, Charles. Clara hid the letters in the attic of the Glendale home she shared with Charles while they pretended to be cousins for the benefit of Glendale society. The bundle came as an unpleasant surprise to Charles who believed all the letters were destroyed.

The lawsuit could get steamy, and Angelenos expected a knock-down, drag-out fight between Grace and Clara.

Clara took the stand, and according to the L.A. Times she testified to “bare the sordid romance that she says ruined her young life.” She told the court how she and Charles Munro met.

“I met him at the corner of Montgomery and Front streets, Trenton (New Jersey). I was working in a Trenton pottery and was on my way to the post office to mail letters for the potter. A big automobile nearly struck me. The driver stopped the car and asked me if I was hurt. When I told him no, he kindly offered to drive me home, after ascertaining where I lived. He said it was on his way.”

According to Clara, Charles persuaded her to get into his car.

“He asked me where I was employed, my house address and telephone number. He did not enter the house.”

Charles phoned her every day and finally invited her out for dinner. He said his name was Darrell Huntington Stewart and he lived in Wayne Junction, PA.

For three weeks, the couple dined at the same restaurant every night until Darrell proposed marriage. The generosity and sweetness of her suitor swept Clara her off her feet. As lovers will do, Charles sent two photos of himself to her and he inscribed them on the backs.

“With all my love to my future wife, Clara Eunice Barker. Your own, Darrell.”

Soon after sending Clara the photos, he asked her to accompany him on a business trip to New York, and she agreed to go. Charles gave Clara her own room, which led her to believe his intentions were honorable.

Late in the afternoon on the first day of their trip, Charles came to Clara’s room. She recalled the meeting for the jury.

“He told me there was no harm in his being there, as we were soon to be married. Whatever happened was all right; it would make no difference; we would be married within a week. I believed him.”

A few weeks after the trip, Clara at last became suspicious of Charles. He’d made no move to set a wedding date, and she said that he always seemed to be in Trenton. He never phoned from Philadelphia, where he told her he lived.

The clue to Charles’ real identity came when she overheard some men talking.

“There is only one man in Trenton who owns a brown automobile of a certain make, and that man is Munro.”

Knowing that her lover, the mysterious Darrell, drove a car matching the description of Munro’s, she did a bit of sleuthing.

Clara phoned the zinc works and asked for Charles Munro — when he answered the phone, she recognized his voice as belonging to her fiancée, Darrell.

“I was horrified. I asked him how he could have done such a thing. He said he fell in love with me the first time we met. He said before he met me, he was preparing to run away with another girl, May Pierson, who was his stenographer…now that he had met me, he would not run away with her. He would get a divorce. He said he had a miserable life.”

After his identity was revealed, Charles cajoled, sweet-talked, and threatened Clara to keep her. Clara stayed.

Early in her relationship with Charles, in January 1915, Clara received a telephone call from Grace. Grace described Charles as “a liar and a hypocrite.” She knew her husband well. Clara had every reason to believe Grace, but she would not give him up.

Charles must have had some uncomfortable moments after his wife and mistress spoke to one another on the telephone. It would have served him right if they’d joined forces and fleeced him for every cent. Sadly, they continued to fight over him instead.

To keep the two women apart, Charles warned Clara to steer clear of his wife, whom he characterized as a terrible person. He told Clara that Grace was likely to hurl acid into her face.

Charles continued to string Clara along with promises of marriage. The pair moved around, finally arriving in Southern California where, masquerading as cousins, they started a new life in Glendale. Clara grew tired of waiting for Charles to make good on his promises to divorce his wife, and in a fit of despair she swallowed poison.

Charles wrote dozens of letters to Clara, and in each one he declared his undying love for her. But Charles realized Clara might not wait for him.

“I know, darling, you are not made of stone, and that you cannot wait very long, and I am pushing everything to the limit so we can soon be together.”

If Charles’ love talk didn’t work its magic on Clara, perhaps threats would. He wrote to her about a dream he’d had.

“I told you if you were not true, I would kill you. But I changed my mind as I wanted to see you suffer. I woke with the most awful yell, and was laughing. But, oh, what a laugh.”

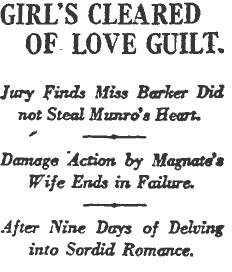

After a trial lasting nine days, the jury of eleven men and one woman deliberated. It took them fewer than six hours to find Clara “not guilty of the love theft.”

Surprisingly, the battle of Wife vs. Mistress did not end with the verdict. A new trial was granted because a judge determined the judgment in favor of Clara was against the weight of the evidence.

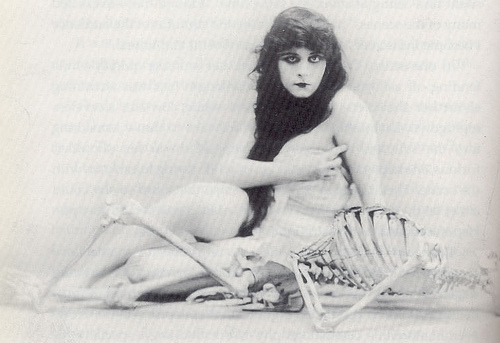

Revitalized by the opportunity for a new fight, and another chance at $50,000, Grace declared Clara was a vampire who had enticed Charles away from his marriage. Grace intended to drive a financial, if not an actual, stake through the heart of her rival.

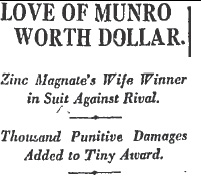

Grace was victorious in the second trial, but instead of the $50k she’d asked for, the judge awarded her one dollar. Clara must have felt relieved that it cost her only a dollar to be rid of Grace.

The judge did not like Grace, but he also disapproved of Charles and Clara. He said,

“The tie that bound Mr. Munro and Miss Barker was low and degraded.”

Low and degraded, she may have been, but Clara was successful in her lawsuit against Charles. She recovered the “love nest” in Glendale. She also got the furniture, bonds, and other gifts he gave her–about $27,000 (equivalent to $436,000 in current USD).

The Munro’s and their attorneys felt Clara didn’t deserve a penny. They said her hands were not clean, and the property given her was the “price of her sin”. A galling statement coming from Charles. Sounds like he and Grace would have sewn a scarlet letter to Clara’s dress if they could.

Judge Wood did not entirely disagree with the Munros, but he seemed to believe that sin is a matter of degree.

“If I distinguish between the two, she is the lesser sinner.”

And to the lesser sinner, go the spoils.